Every year more than 20,000 in the U.S visit the emergency room for carbon monoxide poisoning. Out of those, about 400 die – and that doesn’t include monoxide related deaths from fires. Ryan Morrissey is director of the Central Texas Poison Control Center at Baylor Scott & White in Temple – he explains what makes carbon monoxide particularly dangerous.

“Our usual methods of knowing that we’re in a bad environment – our smell, our taste, our vision – none of those things apply,” Morrissey says. “This is colorless, odorless, tasteless gas. The initial stages may feel like any other illness. You get headache, you get nausea. You could write that off as a virus, a flu, ‘I’m dehydrated, and need to get a little sleep. It’s tricky in that sense.”

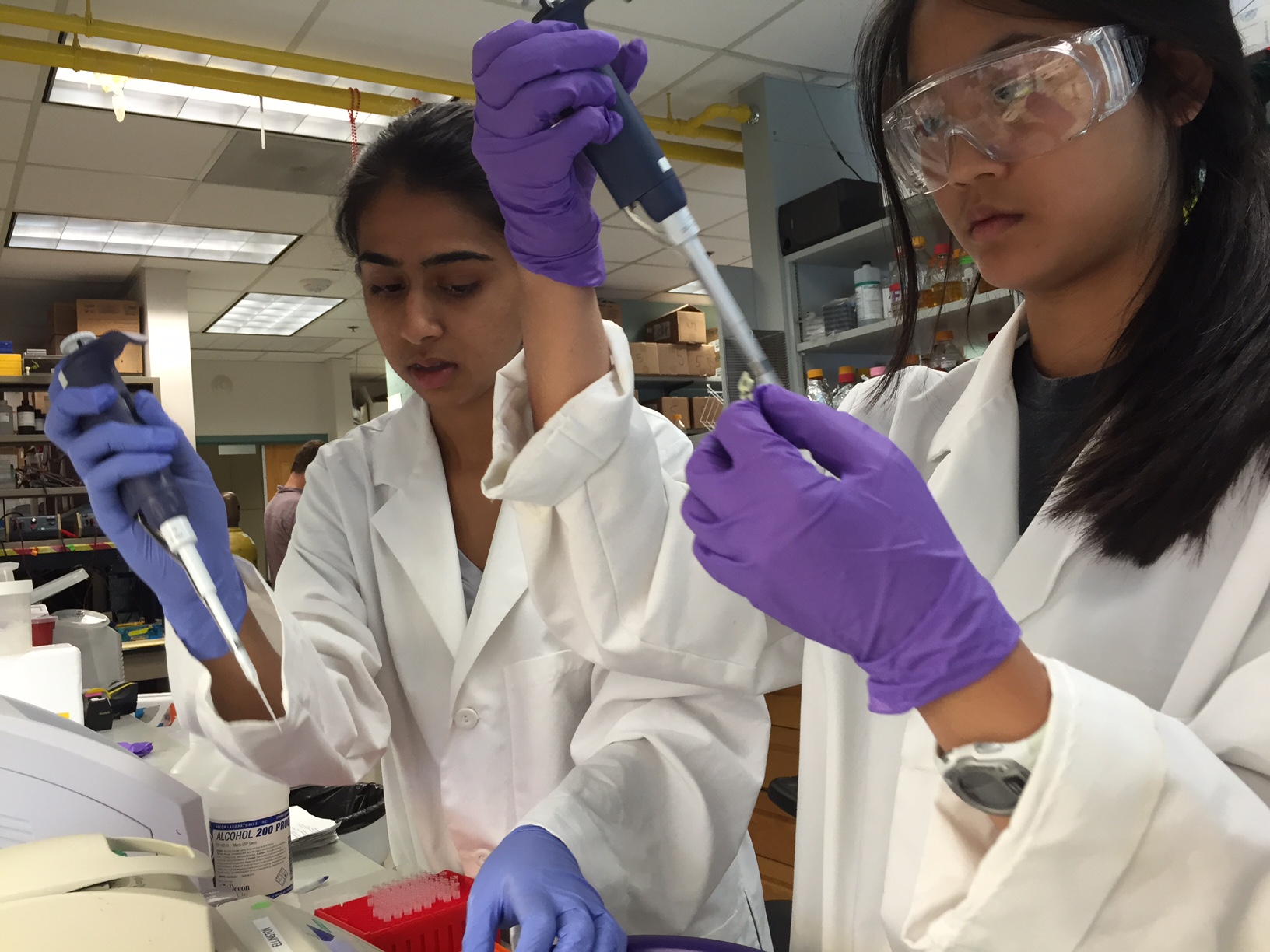

But some high schoolers are hoping to change the way carbon monoxide is detected. Isaree Pitaktong is one of about 15 students from the Liberal Arts and Science Academy in Austin.

“This past school year, and this summer we’ve been working to design and create a carbon monoxide detector that producers a winter green scent in the presence of carbon monoxide,” Pitaktong says. “We’re hoping this can help the deaf and disabled because most commercial available carbon monoxide detectors only produce a sound or change color.”

The project is being developed with the aid of the University of Texas biology department as an entry into the International Genetically Engineered Machine Competition. The key focal point in the design being a biological reaction to the gas.

“We’re engineering bacteria by using known genes that can detect carbon monoxide, and other genes that can produce a wintergreen smell,”Pitaktong explains. “By putting them in a certain order in bacteria we can make this bacteria machine that can detect and respond to carbon monoxide.”

While the research has awhile to go before it ends up on store shelves. Students and UT staff say the findings are just the tip of the iceberg – with biological machines soon being able to detect a variety of toxic gases.