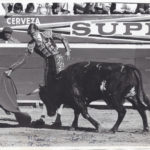

The line between sport and art has always been blurred when it comes to bullfighting. It’s called the “ballet of death,” and matadors, like professional dancers, require immense athleticism, stage presence and talent to master a skill that goes back centuries.

In the U.S., where traditional bullfighting is illegal, bloodless bullfighting – known as the “ballet of life”– has connected two cultures along the border in the Rio Grande Valley for decades.

But the final curtain may be falling on this 20-year tradition, as the man who brought bloodless bullfighting to the Lone Star State takes his final bow – his despedida.

“It’s got to be over”

In the unincorporated city of La Gloria in South Texas, there’s not much to see other than mesquite trees, brush and an occasional roadrunner. But just off Ranch Road 1017, red and orange flags line the fence of a 65-acre ranch. It’s the Santa Maria Bullring, the only place in Texas where there’s bloodless bullfighting.