From KACU:

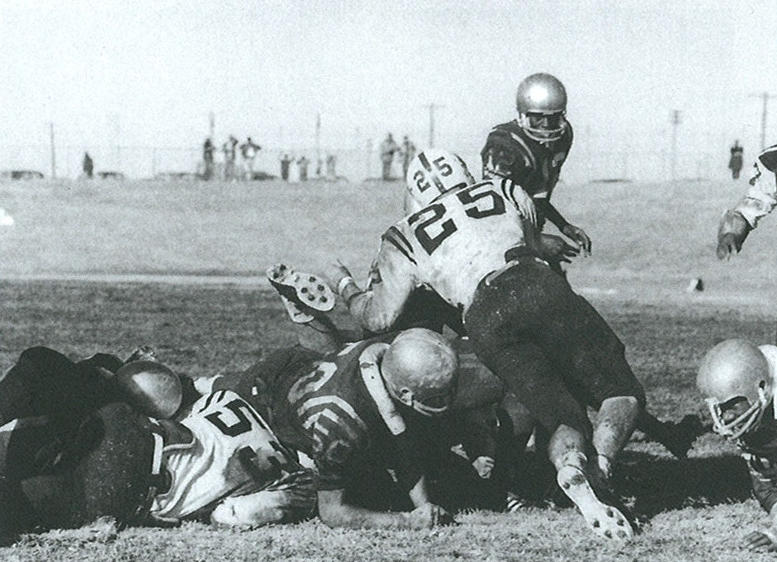

Two-a-days are well underway at Texas high schools as football teams prepare for the upcoming season, only a few weeks remain before those Friday night lights illuminate starry Texas skies. And If you’re a football fan, you may have heard of the Mighty Matadors. In 1968, Lubbock’s Estacado High football team won the Texas Class AAA championship in their first year playing varsity football. Estacado also happened to be Lubbock’s first integrated school.

A new book tells the story of the team that overcame racial division to become state champions. It’s a history that Abilene journalist and author Al Pickett learned about while covering sports but he didn’t know the dramatic backdrop of that story… until some of the players got in touch.

“They came to me, the players on the team wanted to tell their story,” Pickett says. “They thought it was a story that needed to be out.”

His new book, ‘Mighty Mighty Matadors’ was published this summer. Pickett said it covers that championship season but’s about so much more than sports.

“I don’t know if there was a more turbulent year in all of America than 1968,” Pickett says.

Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy had been assassinated, television brought the Vietnam War into living rooms, the civil rights movement rocked the nation. School districts were integrating and for most students, that wasn’t an easy transition.

“I didn’t know anyone, they didn’t know me, no one was speaking to me,” Kenneth Wallace says.

He remembers how uncomfortable he was during those first few weeks. He was shy and had grown up attending one of Lubbock’s all-black schools.

“But when I started playing football, people became friendlier,” Wallace says.

A passion for the sport connected him to his white and Hispanic classmates. Staff at Estacado created a safe haven, for Football Coach Jimmie Keeling, there were no colors…except Matador blue.

“It was an exciting time, one of the huge things that we realized quickly that we had a lot of talent,” Keeling says.

He saw potential in Wallace and made him quarterback.

“He just showed a confidence in me that really I didn’t have,” Wallace says.

Wallace says Coach Keeling forced him out of his shell just in time for the team’s first big challenge – their crosstown match against Lubbock Dunbar – the all African-American school that was kept open. Wallace calls it the game of the century. He was playing against guys he used to go to school with. Estacado’s defense shined and they beat Dunbar, putting them halfway toward a district championship.

“It was just an amazing time for us,” Wallace says. It really was and the more we won, the more excited we got about playing football.”

Next they beat Synder, Colorado City, Sweetwater and Brownwood to become the best in west Texas. Then the best in east Texas. The whole community rallied behind them. And Coach Keeling had earned the respect of every player on his team.

“He’s special to every team member,” Wallce says. “Although I may feel as though I had the best relationship with him, you know that’s what I feel. But every one of our players feel the same way.”

Keeling cultivated those relationships throughout the season, he also worked to unify his team.

“We had a little five minute talk every day at the beginning of our athletic period talking about what we could accomplish, what we could do, how important it was to pay a price to make good things happen,” Keeling says.

Building that work ethic and confidence was important to Keeling. Many of his players lived in poverty. Some were ostracized by their families because they chose to attend an integrated school. He encouraged them to have hope for a bright future.

In their final game, their defense held the best team in south Texas at bay allowing them to take the Texas title. The Matadors were euphoric over the victory. But that wasn’t the end of their success.

“The thing I’m most proud of is that today, basically 50 years later, how great all those people have turned out,” Keeling says. “They are great men.”

Quarterback Kenneth Wallce says his entire life was shaped by the values he gained during those formative years.

“I’ve had a good career and I think it all started right there at Lubbock Estacado High School with the things that we were able to do there: the discipline, the leadership,” Wallace says. “It just was a carry over but not just for me, but many of my teammates.”

Some of the Matadors later learned integration wasn’t always as easy as it had been at Estacado. But the brotherhood they developed proved that embracing differences, rather than fearing them, can lead to tremendous success.