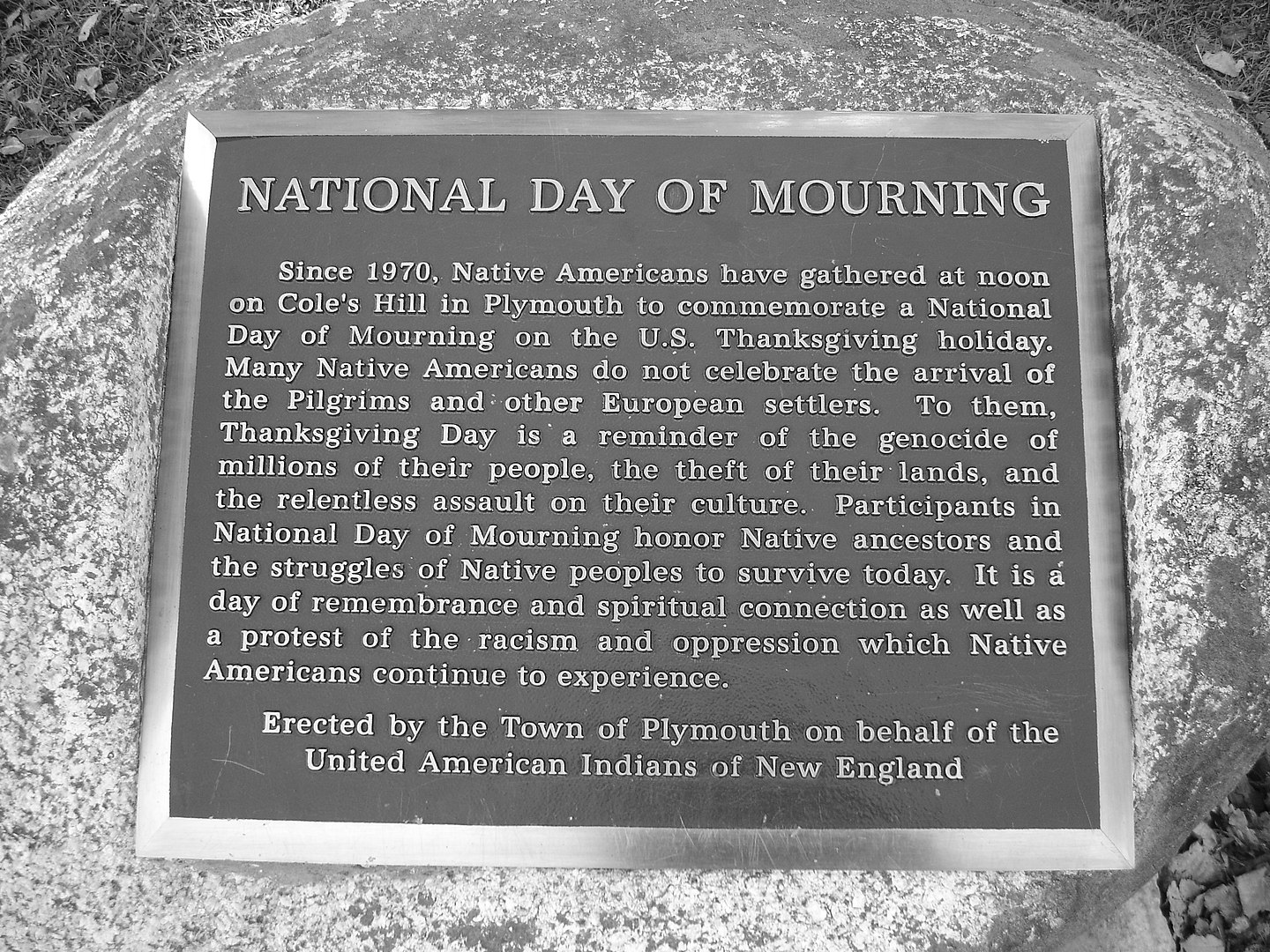

For some Indigenous Americans, Thanksgiving is not a day for celebration. The United American Indians of New England actually declared it a National Day of Mourning in 1970. But the traditions vary widely, with others focusing on the blessing of a successful harvest.

Talking to kids about the holiday as a time to focus on what we’re grateful is easy. It can feel trickier to explore the truth behind the historical first Thanksgiving, and the way Indigenous people have been treated. But Marleen Villanueva says it doesn’t have to be complicated.

“Every year, as you continue to develop a relationship with the native, Indigenous peoples of the lands that you’re on, you have more to share with your young one, and your young one’s going to learn through actions,” Villanueva said.

Villanueva works for the Indigenous Cultures Institute based in San Marcos. She is a PhD student at the University of Toronto in Social Justice Education. Villanueva spoke with Texas Standard about taking steps towards more understanding about native histories and current experiences. Listen to the interview with Villanueva in the audio player above or read the transcript below.