How many little kids – after watching movies like “Indiana Jones” or “Lara Croft: Tomb Raider” – dream of growing up exploring little known parts of the world, risking life and limb in search of long lost treasure?

How many people actually end up living that dream?

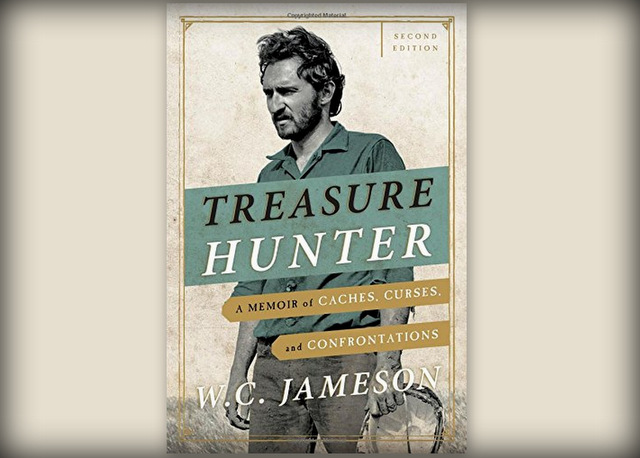

Not many. But W.C. Jameson has lived that dream for six decades on and off. He’s a Texas author, historian and Treasure Hunter. He’s detailed some of his adventures in a book, “Treasure Hunter: A Memoir of Caches, Curses, and Confrontations.”

He was also willing to share some of his rich wisdom with the Standard.

“My first treasure hunt took place when I was 11 years old. I was conscripted by four professional treasure hunters as a chore boy: camp-hand, cut wood, keep the fire going,” Jameson says. “But I did get to participate in the recovery of 100 gold ingots. We retrieved them from a cave where they had been hidden for about half a century or so.”

He handled some of those 25-pound ingots, and was transformed.

“I’ve since described it as a very electric feeling. That kind of took over and following that experience I read pretty much everything I could. I read ‘Jason and the Golden Fleece’ – which is basically a treasure hunt. I read the great book by B. Traven, ‘Treasure of the Sierra Madres.’ What kid hasn’t read ‘Treasure Island,’” he says. “I found the most fascinating part of this was the actual quest for the treasure. This is the stuff that great stories are made up of. It’s not so much the finding of the treasure, it’s the search for the treasure.”

Jameson says he partnered up with three other men to professionally treasure hunt. They worked together on and off for a little over 30 years. He says the spoils of his quests have made him rich at times, but hauling treasure from remote areas isn’t as easy as it sounds.

“What a lot of people don’t understand is that discovering treasure is often not quite as hard as recovering treasure,” he says. “If you find 25 to 40 pound gold ingots in a remote part of Mexico where there are no roads, where there are no trails, the question is how do you get this out? You got four guys with backpacks.”

The found money usually goes into financing transportation and the next expedition, plus its split up between the seekers. Jameson says it’s also rare to find Spanish gold bars that are more than 60 to 65 percent gold. The smelting process way back when including a lot of impurities like copper, lead and other materials.

His holy grail? Jameson says there are many, but the best story is the Lost Dutchman Mine of the Superstition Mountains in Arizona.

“It’s a great story that’s been looked for so many times it’s been told and re-told so many time it’s sometimes very difficult to separate the fact from the made-up stuff there. It remains a good story – the truth is, those mines are not so much lost as they were just simply mined out,” he explains. “You still can find gold in the Superstition Mountains, and if you’re really good at this you can go in and come out with enough gold to maybe pay for your trip out there and back.”

But Jameson says beware the hazards of the mountains. Besides being cursed, hunters could get caught in flash floods or have a few run-ins with rattlesnakes.

“As someone who has done this for probably six decades or so, as far as I’m concerned they’re all cursed,” Jameson says. “They all have their obstacles.”