From Texas Public Radio:

State authorities in Nuevo León, Mexico report two armed men hijacked a truck carrying 1,600 containers of drinkable water from Reynosa to Monterrey last Saturday.

The incident occurred on Mexico’s Federal Highway 40, just north east of Monterrey — where a water restriction policy allows residents only six hours of running water per day.

However, many residents say that actual access varies greatly across the city.

In the municipality of Guadalupe, where the hijacking incident occurred, residents delivered a letter in protest to the local water utility this week, claiming they have been without running water for two months.

Police have yet to identify any assailants in the incident.

Just across the Texas-Mexico border, Marilu Lopez is the owner of Agua Purificada Anzur — one of dozens of small independent purified water delivery service providers in Reynosa.

Businesses like the one run by Lopez are not part of any planned water supply infrastructure, but they supply a significant portion of drinkable water to the population.

Lopez says Anzur considered supplying purified water at cost to aid people in Monterrey — a two-hour drive from their supply location. However, Lopez ultimately decided against it.

“There are people in Monterrey who’ve wanted water deliveries from Reynosa, but they have their own rules now about who is allowed to sell water in Monterrey. Out of fear of making that trip, we only sell locally.”

Lopez said the same water shipments that Anzur delivers in Reynosa can currently sell for prices up to about five times higher in Monterrey. At that rate, the truck intercepted in Guadalupe was carrying about $8,000 worth of water.

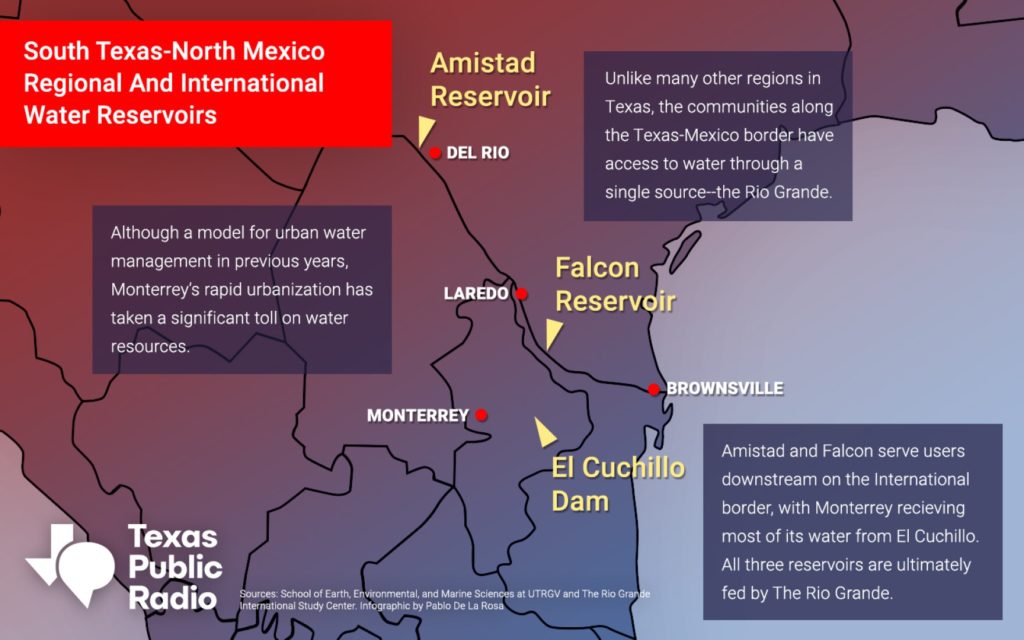

Experts working near international water reservoirs on the border say that the severe drought currently happening throughout the American West and Northern Mexico may soon have dire effects across South Texas as well.

Martin Castro, the Watershed Science Director at the Rio Grande International Study Center (RGISC) in Laredo, said they are seeing alarming reports in water levels.

“Falcon is dropping drastically from week to week,” said Castro. “I mean, a week ago it dropped a foot.”

The International Water and Boundary Commission (IWBC) is currently reporting water levels at just 23% capacity at Amistad Reservoir north west of Del Rio, with water levels at only 11.5% at Falcon International Reservoir south of Zapata.

The numbers represent a severely depleted capacity for the two reservoirs that supply virtually all communities downstream with running water along the border.

When asked if it is possible that Zapata County and the Rio Grande Valley could run out of water in the next few weeks, Castro responded, “It doesn’t look like things are improving so it’s a real possibility. I can certainly see that happening. But a lot of the public is not aware of this. There’s a lot of lack of communication to the public about conserving water.”

According to Dr. Jude A. Benavides, a hydrology research scientist in the School of Earth, Environmental, and Marine Sciences at UT-RGV, a combination of major weather cycles across the tropical Pacific Ocean and the intensifying effects of climate change have coincided with a third consecutive year of seasonal drought — creating one of the most intense water scarcity crises in recent history.

“It’s important for folks to understand that the Rio Grande Watershed, particularly the lower but the entire watershed, is amongst one of the most water challenged in the world,” said Benavides. “Which means that when we get a drought, we become even more water scarce.”

Through his work with municipalities on the border as a member on the board of the Southmost Regional Water Authority, Benavides has learned that the end of this drought will not mean an end to water scarcity.

“The challenges are going to grow, regardless of what climate change does simply because of our increased population growth,” said Benavides “We are shifting from an agricultural sector here in the valley to more of an urban industrial sector – that water must be treated for drinking purposes, and that adds cost.”

South Texas-North Mexico regional and international water reservoirs

Sheila Serna, Climate Science and Policy Director at RGISC, said the regional energy industry has also played a role in the current situation.

“A lot of people don’t realize that in many stages of energy production — coal, natural gas and oil production — there is a lot of water that is required,” said Serna. “So a lot of the times cities will put a water restriction, but the burden falls on the citizens.”

Serna explained that placing water restrictions on energy production may be one of the most impactful ways of addressing the current crisis.

“I know they sound like long-term solutions, but methane has 80 times the warming power that carbon dioxide has,” said Serna. “So if we were to already start implementing those changes, we would pretty rapidly see the benefits.”

However, Benavides said that like any natural climate cycle, there is still the possibility that the drought may come to an end in the next few months.

“The Rio Grande is historically known for being Bravo (untamed) — the ‘Rio Bravo,’” said Benavides. “Meaning often very, very low flow for prolonged periods of time, and then suddenly flashing floods.”

Serna said the river as a water source is something people from the region sometimes sidestep as a responsibility.

“A lot of people feel disconnected to it because there’s a lot of turmoil around it,” said Serna. “But at the end of the day, it is our one and only water source.”

“It is a life-giving river for most of us in Laredo, San Ygnacio, Rio Bravo, El Cenizo. So, it’s very important. It’s a top priority to take care of it.”