Sandra Edwards lives on a dead-end street in Fifth Ward, which sits on top of a plume of contamination from a former industrial facility where wooden railroad ties were treated with creosote — a chemical mixture that has been found in the soil and groundwater of at least 100 homes in the area.

As she walks down the block on a recent Wednesday afternoon, she points out all the neighbors that are no longer around — Miss Lucille, Sophie Lee Mitchell, Mr. Dunn — until she loses count.

“How many is it so far? It’s like the whole street died from cancer,” Edwards said.

Over the past two years, state officials have conducted health investigations in the Kashmere Gardens and Fifth Ward neighborhoods. And the most recent report, released last month, identified another cancer cluster of lymphoblastic leukemia in children after analyzing data from 2000-2016 within a two-mile radius of the facility, which is now owned by Union Pacific Railroad.

In one census tract that includes the railyard, this cancer was nearly five times the baseline rate.

“This was like a brick fell on my head,” said Edwards, who is president of the community group IMPACT. “Even though we kind of suspected it, we wasn’t expecting it to be as bad as it was.”

Previous reports have confirmed higher rates of acute myeloid leukemia, esophagus, larynx, liver, lung and bronchus cancers in adults.

For many residents, it seems obvious that poor health in the community is driven by the contamination. Multiple regulatory agencies recognize creosote as a probable carcinogen. However, state investigations have determined proving the cause of such high cancer rates is not feasible due to limited data.

Residents are demanding accountability from Union Pacific. They’ve asked to be relocated, for their health care costs to be paid and for the area to be declared a Superfund site by state and federal environmental agencies.

“We don’t know what’s next, but we know what we want,” Edwards said. “They need to do something. We are tired of being sick and tired over here.”

Sandra Edwards wears a “Creosote Killed Me” shirt, which were made in response to the creosote contamination allegedly caused by the Union Pacific Railyard. Taken on Jan. 27,

Lucio Vasquez / Houston Public Media

Dianna Jackson, a resident of Kashmere Gardens, isn’t interested in relocating because she’s 65. At a meeting last week, she told Harris County commissioners that she wants the area cleaned up.

“If (the contamination) were anywhere else — River Oaks, The Heights, Meyerland — this would have already been taken care of years ago,” Jackson said.

Residents have filed multiple lawsuits against Union Pacific, and negotiations over managing the waste are ongoing with state environmental officials.

Shortly after the report was publicized, Mayor Sylvester Turner issued a statement requesting that Union Pacific fulfill these demands.

“I am requesting that Union Pacific help to relocate affected residents and create a buffer between contaminated areas and homes in the neighborhood,” Turner said.

The Union Pacific Railyard, located near Kashmere Gardens. Residents say the railyard is responsible for the cancer cluster in Kashmere Gardens. Taken on Jan. 27, 2021.

Lucio Vasquez / Houston Public Media

Union Pacific declined a request for interview, but in a statement, the company said it “continues to follow the science as we evaluate the updated assessments. At this point, decades of testing show no exposure pathway from Union Pacific’s site to any resident.”

The Houston Health Department’s most recent sampling of locations above the groundwater plume took place late last year. An analysis found levels were around or below the reporting limit.

Dr. Robert Bullard, an urban planning and environmental policy professor at Texas Southern University, said the cancer cluster is a result of a history of Jim Crow, housing discrimination and unequal enforcement of environmental laws and land use.

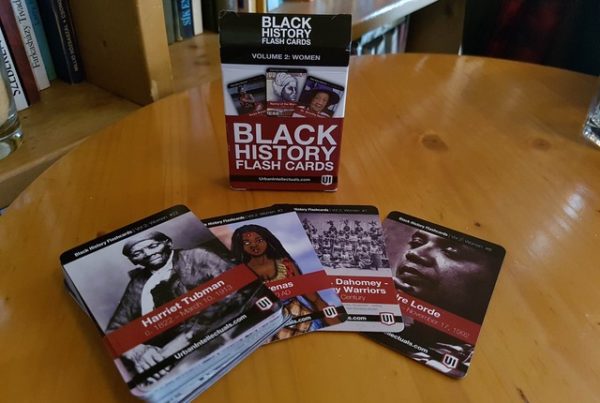

Several houses on Lavender Street have been abandoned after their owners died from cancer. Taken on Jan. 27,2021.

Lucio Vasquez / Houston Public Media

“This is the textbook case of environmental racism that we have been fighting since 1979,” Bullard said.

His research shows that icinerators, private and public landfills and other waste facilities have been disproportionately placed in Black neighborhoods on the east side of Houston. As a result, these communities bear the highest cost to their safety, health and property values.

“A disproportionate share of the residents who live on the fence line don’t work at the plants,” said Bullard. “Usually the jobs are for people who drive in and drive out. That’s the irony of environmental injustice. The cost and benefits of environmental protection and the benefits are not distributed equally across the board.”

Accountability is often a long journey that communities are forced to fight for, Bullard added.

“Even when the discovery is made, it takes decades in some cases for these communities to get justice,” Bullard said. “Justice is more than just getting sites cleaned up, it’s making these communities whole.”