From KUT:

A 17-year-old girl who entered the U.S. without documentation or family told the staff at a Texas shelter in March that she wanted an abortion.

The shelter is one of many in the U.S. under contract with the federal government to provide services to unaccompanied children (UACs). Those services include food and shelter, as well as health and education services.

The young woman had to follow the same complicated process that any minor seeking an abortion in Texas without a parent’s consent must follow. She was allowed an attorney, and a legal guardian was appointed. A judge eventually allowed her to go ahead with the abortion without a parent’s consent.

On a Friday, the teenager was released by the shelter to get an abortion.

“She was early enough to have a medication abortion,” says Susan Hays, an attorney familiar with the case. “So, she gets pill number one on Friday, and the shelter workers took her back to the shelter with the second pill and instructions to complete the doctor’s orders.”

Then, Hays says, around 5 p.m. that same day the shelter received a phone call from someone at the Office of Refugee Resettlement. ORR is the federal agency that has custody of unaccompanied minors who enter the U.S. without documentation.

Hays says the person calling the shelter claimed to be a doctor at ORR and asked questions about a specific patient, which the shelter workers weren’t at liberty to share. She says he also asked about medication abortions.

According to court documents filed last week in Garza v. Hargan, another case of an unaccompanied minor seeking an abortion, ORR officials told this particular shelter not to give the young woman the second pill.

“That is extremely dangerous because a woman can become septic from leftover tissue in her uterus,” says Hays, who helps minors in Texas seeking abortions through a group called Jane’s Due Process. “And sepsis can kill you.”

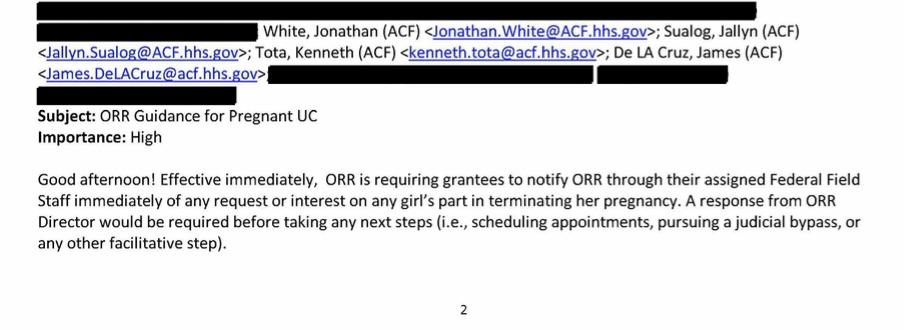

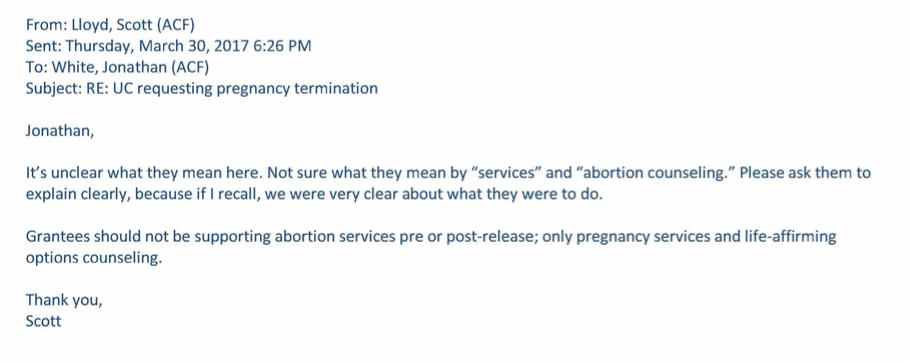

A change of policy

Hays says she was tipped off to the incident shortly after the young woman was denied the second pill required to complete the abortion.

According to court documents in Garza, what stood between the young woman and that second pill was a memo written on March 4.

The memo was written by Ken Tota, the acting director of ORR at the time.

In addition to directing the shelter not to give the young woman the pill, Tota’s memo directed the shelter to take her to a local hospital. He wrote:

This memorandum directs ORR to bring the UAC to the emergency room of a local hospital in order to determine the health status of the UAC and her unborn child. If steps can be taken to preserve the life of the UAC and her unborn child, those steps should be taken. If it is confirmed that the unborn child has already expired due to the beginning of the abortion procedure, steps can be taken to safely remove the body of the unborn child.

That Sunday, Hays says, the shelter followed the directions and subjected her to a gynecological exam.

“That was not a necessary medical examination,” Hays says. “It was not one she could have possibly consented to, because she wasn’t told the purpose.”

Hays says the shelter opened itself to possible litigation.

“A medical exam without consent is assault. A gynecological exam without consent is rape. And the federal government did that to that Jane,” she says, referring to the legal name Jane Doe given to minors in these situations. Cases involving minors are often sealed.

The most sweeping aspect of that March 4 memo, though, is that it outlined a new policy for ORR:

With the exception of emergency medical situations, when a UAC may be involved in an abortion, grantees [shelters] must immediately inform the director of the Division of Unaccompanied Children’s Services (DUCS or DCS) in ORR of the situation, must respond to DUCS’ requests for information, and are prohibited from taking any action that facilitates an abortion without direction and approval from the Director of ORR.

In short, the new policy was that a shelter could not facilitate an abortion without the director’s approval.