Doctors have been treating people with the same ailment in different ways for a long time. They consider a person’s family history – and whether they’re a man or woman. That’s precision medicine at its most basic.

Obama’s new budget includes $215 million to expand what we know about genes, microbes and our environment’s impact on how we might react to drugs or a disease.

Dr. Mini Kahlon is part of the first leadership of UT-Austin’s new Dell Medical School. She has a background in neuroscience and she’s well versed in precision medicine. She’s also been personally affected by it.

“My son, when he was born, went through newborn screening like all babies do. He ended up coming up positive for some extremely rare disease related to digestive issues. The implications were that he was either going to die in a few weeks or in four years and the question was just how long and how many mental issues there would be in that short period of time,” Kahlon says.

Dr. Kahlon says the diagnosis came with no options for what to do, no way to help her child. She felt helpless. And that’s something she says physicians will have to consider when using precision medicine.

“We’re going to have to balance the fear and the concern that I went through as a mom, that I’m sure others would go through as well, with really saying, ‘well I do want to know because I want to know if there’s anything I can do about it,” Kahlon says.

Further testing showed Kahlon’s son was ok. The original test was a false positive. It’s an example of major room for growth in in the field.

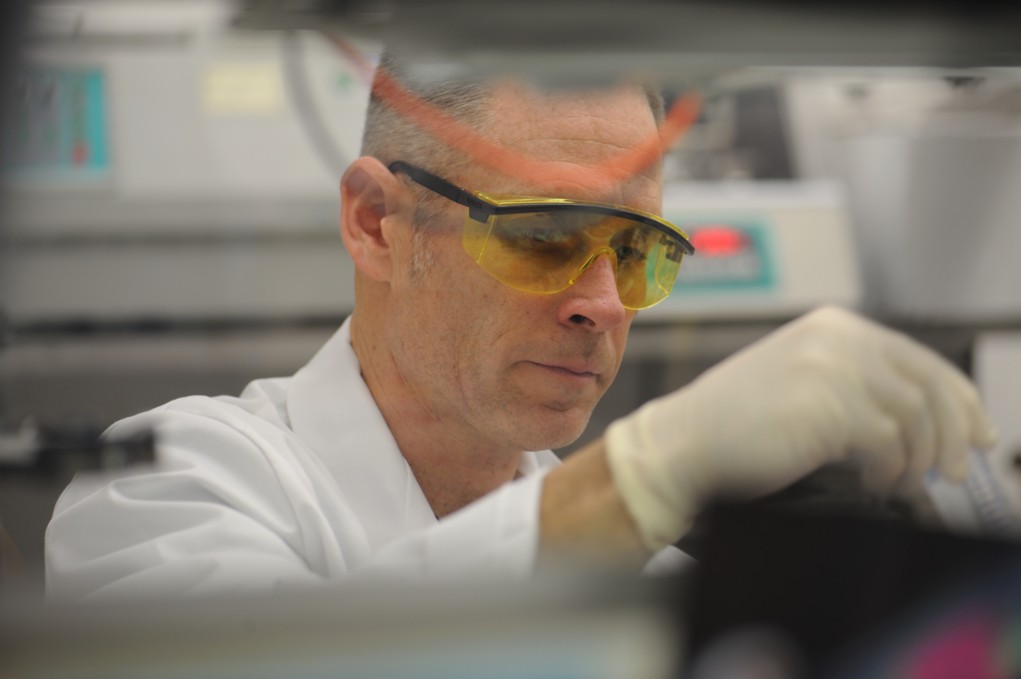

“Not only getting the right genetic data and figuring out what kind of genetic data is most useful but also asking how do we improve our clinical data. You can’t connect genetics, proteomics to clinical data if the clinical data are not precise,” Kahlon says.

Doctors aren’t the only ones interested in advancements.

Pharmaceutical companies are also rejoicing at Obama’s push for more research and development.

Jim Greenwood is President and CEO of the Biotechnology Industry Organization – which represents companies including Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson.

Before taking the job, he was running for a seventh term representing Pennsylvania in the U.S. Congress. But he decided it was time for something new – and found himself passionate about biotech.

“We can literally reach in our body, pull out our DNA, put it under the microscope and, from what we learn, we prevent a couple from burying its child, we prevent someone from turning to his wife of 50 years and asking, ‘who are you?’” Greenwood says.

He also represents another sort of genetics company – Monsanto. But, unlike Genetically Modified organisms – or GMOs – Greenwood says precision medicine is largely uncontroversial.

“There’s nothing partisan about this. It’s not about ideology. This is really a science question. As long as we get the science right, so that everyone can actually agree that this actually will wield results, I think we’ll have a kind of Manhattan project for human health,” Greenwood says.

But there’s at least one big critique of precision medicine – the cost of the drugs discovered.

“The odds are that 1 in 10,000 compounds that you put in the laboratory will ever become a drug. Most of your projects fail, most biotech companies fail and, even of all of the drugs that are eventually approved by the FDA, 80% never recover their costs. And so, when we do produce a drug, frequently they’re very expensive,” Greenwood says.

Dr. Kahlon says another concern is privacy.

“Certainly we’re going to have to ask good and important questions about what the current state of affairs is, how do we manage information that we’re collecting – that is already being collected – so that we’re safeguarding ourselves but also doing all that we can to improve the health of all,” Kahlon says.

So is Texas moving those initiatives forward?

Greenwood says it looks promising and it starts with researchers at Texas’s world-class universities.

“So you have all these brilliant, young researchers at the universities and then what you do, and Texas is doing this very well, you create intellectual property patents and you spin out little companies. And Texas does a very good job of incubating those companies and allowing those companies to survive long enough to attract venture capital and so forth,” Greenwood says.

Greenwood says biotech companies are lobbying the Texas legislature to keep this momentum by continuing the Texas Enterprise and the Emerging Technologies Funds – which Governor Greg Abbott says he’s reevaluating.

Kahlon says the new Dell Medical School will tackle issues not just of Precision Medicine but what she calls Precision Health – using data to determine how to improve health and prevent illness.… taking not just genetic but perhaps zip code information to find out why a child is obese.

“You can learn a lot about how dangerous the neighborhood their living in – that tells you, ‘wow, this kid is probably finding it really hard to walk around his or her house – that then takes us to precision health,” Kahlon says.

They’re more than just concepts to Dr. Kahlon. She still remembers all too well the pain and drama of the diagnosis of her son that was not as precise.

“I’m holding him in my arms, I get this result. The result has some kind of probability to it. That moment is actually a moment that we are all going to have to grapple with when we start using some of this information to start doing the predictive part of precision medicine,” Kahlon says.