Trees are scarce in the Texas Panhandle. Big trees are even scarcer.

The region is droughty and windy. Blizzards and hail are common. Adequate soil is hard to come by. So for some, the few tall trees that survive are precious.

“To me, trees are sacred in this part of the world,” says Lacey Carter Vardeman. “We just don’t have very many.”

Vardeman raises cattle and cotton on two parcels of land in the Panhandle: one in Lubbock County, another in Bailey County – about 10 miles from the Texas-New Mexico border.

Vardeman started buying land in Bailey County about 25 years ago. A few times a week, she and her children would drive the hour-and-a-half between her two properties. It’s not the most scenic route – mostly flat pastures and irrigation pivots. But there was one sight the Vardemans always looked forward to toward the end of the drive: an elm tree.

“We used him as a landmark, because he was so big,” Vardeman says. “He was just huge and pretty and there were a lot of deer under him a lot of times. There’s no telling what’s lived in him and under him for all those years.”

Vardeman’s kids called the tree ‘the mayor of Baileyboro’ – a nod to the name of the now-mostly-deserted spot the tree presided over. There was nothing else like it for miles. By any standard, the mayor was a big tree: about seven feet around, with long, arching branches that scraped the top of trucks and trailers.

The tree sat on the fence line of a neighbor’s property. Vardeman thought it was at least 130 years old – it’s referenced in journals by early settlers of the county. It was there before the Vardemans, and they thought it would be there long after them.

But one day a couple of weeks ago, Lacey got a call from her daughter Molly, who was driving to the Bailey County property to pick up a few of her things. Molly was excited – she’d just been accepted into the master’s program of accounting at Lubbock Christian University. But as she neared the property, rounding the curve where the mayor normally comes into view, her elation faded.

“I pulled around, and the tree was on its side, and I was like ‘Aw, man,’” Molly says.

The tree’s owners cut it down. Vardeman says her neighbors wanted to build a new fence, and the mayor was in the way. It had practically absorbed one of the old T-posts.

“I didn’t know anything about it ‘til it was too late, so, I couldn’t have done anything about it. He wasn’t my, on my property. But just couldn’t believe somebody cut down a tree,” Lacey says.

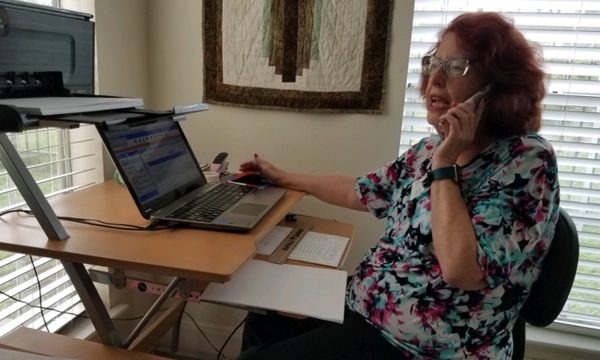

Lacey hung up with Molly. Five minutes passed. Then she picked up the phone again, and called her neighbors.

“I just figured, well I’ll call and ask if I can at least have a piece of him,” she says.

Her neighbors said that was fine – they’d just planned to cut the tree up and burn it anyway. If Lacey could haul it, she could have it. So she did. With help from her kids, she used a John Deere loader to get the tree onto a 34-foot gooseneck trailer. A few other neighbors stopped by to say they appreciated her saving what she could of the tree. It seemed like a shame not to – even if it was hard work.

“We had to cut a lot of the bigger branches off of him, because it was so heavy my loader wasn’t able to pick it up,” Lacey says. “It kinda took up most of [the trailer]. I think we decided he weighed over 10,000 pounds, the part that I actually brought home.”

Which is where it is now – sitting by her haystack, waiting for what’s next. Replanting isn’t possible, so Lacey plans to give some of the wood to each of her kids.

She’s looking for a carpenter to make rough-cut tables out of it, someplace where people could gather or share a meal. For Molly, it’s a way to show reverence for something that persevered for so long in place where it can be so hard to stay alive.

“It’s amazing to think that this tree’s gone through World War I, World War II, the Dust Bowl. It’s gone and seen all of the hard times and the good times of the area,” she says. I’m really impressed that things are able to live and last that long, especially as hard of an area as it is around here.”