Editor’s note: Texas Standard reached out to state Rep. John Raney, the main author of HB 1694, and a couple of the other listed authors, for more understanding on what the bill was designed to accomplish. As of air time, we have not heard back.

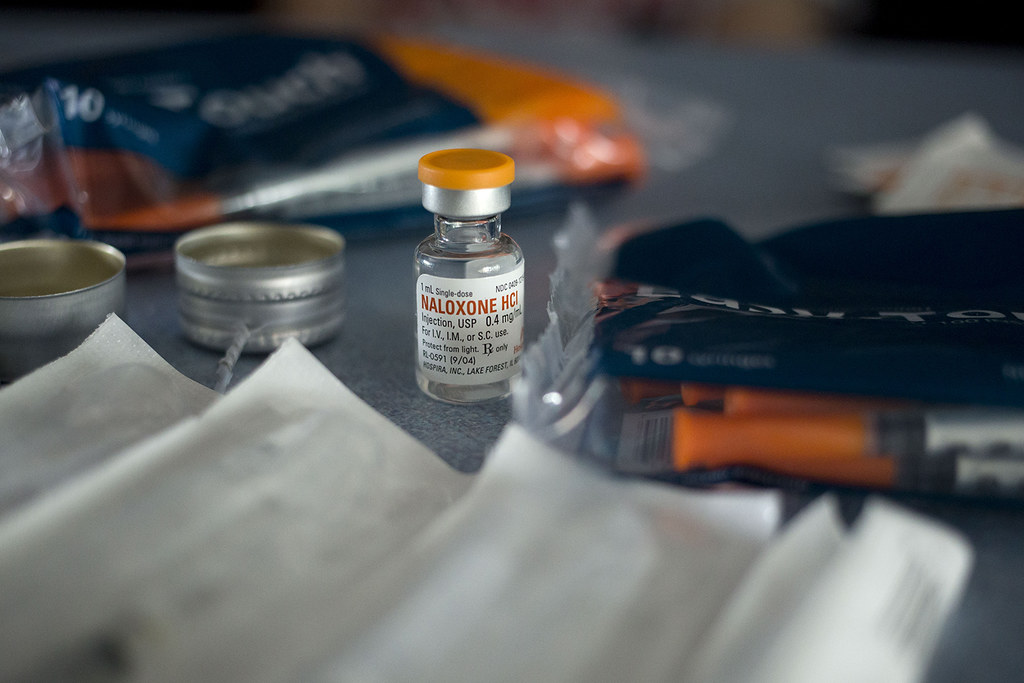

Drug overdose deaths rose sharply during the pandemic. Researchers point to social isolation, economic stress and a lack of access to treatment as major factors. But witnessing, or even experiencing an overdose yourself, in Texas, can expose you to potential legal trouble if you call for help.

A new so-called good Samaritan law passed during this year’s legislative session is meant to ease some of those restrictions, and encourage people in distress to call 911. But, it comes with many caveats.

David Johnson is policy liaison for the progressive advocacy group Grassroots Leadership. He tells Texas Standard that the law is only a very small step toward solving the much bigger problem of addiction and incarceration. Listen to the interview with Johnson in the audio player above or read the transcript below to learn more about the law, its restrictions and what effect it could have on drug-related incarcerations in Texas.

This interview has been edited lightly for clarity.

Texas Standard: Let’s talk a bit about what House Bill 1694, as it was known before it was signed into law. What was it trying to do?

David Johnson: Well, first I want to make the point that it is not a good Samaritan bill. It is much less. It is a very diluted, almost ineffective bill that equates to an overdose bystander law. And what it is trying, what it purports to try to do, publicly, is create a space for individuals to ensure that those who experience overdose still have access to lifesaving care without having to worry about people moving away from contacting emergency services out of fear that they will be prosecuted or incarcerated as a result of some drug charge related to that use.

However, what it actually does is it creates a space for people who enjoy a number of privileges and access to privileges and wellness in our culture, and in our community, to have an extra get-out-of-jail-free card.

Who remains vulnerable to prosecution under the terms of this new law, as you see it?

That’s a great question, and I think the best way to answer that is to go through what some of the terms are. First off, one of the conditions is that you cannot have called 911 within the last 18 months. Another condition is that you cannot have ever used the bystander overdose defense before. Another is that you cannot have called for another overdose within 12 months.

Who that leaves vulnerable is really who you have left when you look at those who will only, in their experience, be in the presence of one overdose. When, in fact, in a moment of emergency crisis, of life-and-death choices, a life-and-death situation, no one should have to worry about the punishment that could come from doing the right thing in that moment. And this also treats drug users as though they are a one and done when, in fact, most people who experience overdose do so after using drugs repeatedly and habitually in their life.

The Biden administration recently announced plans to use so-called harm reduction methods to deal with addiction and overdoses. I’m curious about where Texas’s new law might fall on the spectrum of harm-reduction efforts compared to other states.

Harm reduction is about mitigating the life-threatening harm that comes from individuals choosing to do drugs, which, if we’re going to be very honest, most people have done, most people have done more than once. And so the thought that someone deserves to die or that someone surrenders their humanity because they choose to do drugs, and lack the access to wealth and power to make sure that they never suffer the consequences of a criminal legal system that’s racist and classist and targets them for their use, that’s absurd; that’s, like, my favorite word of the day.

Research over the decades has shown that Black and Latino Texans have been incarcerated at disproportionately higher rates for drugs than other groups. Your organization found similar trends in Austin’s Travis County. What effect do you think this law might have on that problem if, if at all?

I think it’ll have slim to no effect, and slim is walking out the door, as we like to say. One of the other additional conditions of this bill is you cannot have a felony drug conviction. I’ve been arrested 49 times and I’ve been to prison three times, and my life looks very different now. So that means if I were to come across someone overdosing, I am not protected if I call 911 because I have felony drug convictions. And so when we look at how it will impact Black and brown folks, non-white folks, poor folks, those folks hold the greater percentage of felony drug convictions. They are more likely to have been witness to more or been present for more than one overdose. They are more likely to live in communities that are hyper-policed to begin with so that they have those experiences.

If you had the ear of Texas lawmakers, what would you say to them about this law? Is there somebody who’s getting this right?

I don’t think it’s so much a governmental player, but I will say Oklahoma – look to the state of Oklahoma. There they have decriminalized paraphernalia so that you’re able to have needle exchange and you’re able to have pipe exchange, and giving people access to trauma care and to deepen behavioral health care so that they can deal with the issues that lead to the substance misuse, right?