This week, Merriam-Webster deemed “justice” its 2018 word of the year. Two other dictionary publishers chose words of the year that seem a bit bleak by comparison: Oxford chose “toxic,” while dictionary.com chose “misinformation.” But there’s another buzzword that’s just as relevant this year that neither chose: civility.

Civility used to merely denote politeness or courteousness, but the term has become controversial and politically charged with the rise of social media and today’s tumultuous political climate. People on all sides of the political spectrum are calling for more civility, but critics, including Dr. Jennifer Mercieca, say the word won’t save us.

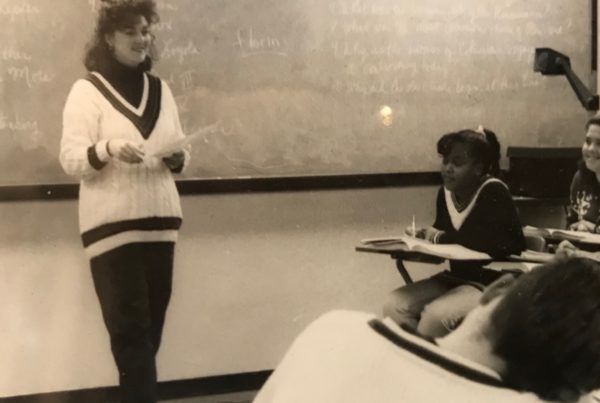

Mercieca is an associate professor specializing in political rhetoric at Texas A&M University’s School of Communication, and says much of what’s published today about civility is misguided.

“That we shouldn’t interrupt people at dinner, you know, if we don’t like their politics,” Mercieca says. “I don’t think that those are the best examples. …I think that focusing on civility is sort of a red herring. I mean, it’s a symptom of a bigger problem.”

Mercieca says the bigger problem is that we are conditioned to communicated as propagandists rather than as citizens.

“Everything from the way that our phone is designed to the apps and the algorithms that control the things that we interact with all day … are designed to make us as engaged as possible and as engaged in a way that is going to attract the most attention,” Mercieca says. “The things that are amplified the most are not necessarily the most productive takes.”

Mercieca says today’s media ecosystem gets in the way of productive communication, and can lead to poor decisions. She says because of this, we could be on the brink of another “age of catastrophe” – a term coined by a historian of the first and second world wars.

“[At that time] we started to realize that maybe the people who were in charge didn’t always have the best in mind for everyone,” Mercieca says.

She says today, that applies to technology companies whose designs and algorithms deeply affect everyone’s lives.

“Their goal is to make money,” Mercieca says. “And one great way to make money off of people is to get them addicted, and it’s not the best way to design a public sphere.”

She says advancements in communication technology, as well as the prevalence of propaganda, were significant parts of the last age of catastrophe. Mercieca says it’s the same today.

“We all now have the power of propaganda in our hands, in our back pocket, in our purse, and we never leave that power behind – we keep it with us all the time,” Mercieca says. “We all engage with the world as propagandists now.”

Mercieca says the problem with that is most people don’t have the training or deep understanding of how media works, so they can easily misuse technology or fall victim to propaganda.

“They don’t know what is a good thing to tweet or to spread around and amplify,” Mercieca says.

She says people can educate themselves through things like TED Talks from media and technology experts. She also says turning off cell phone notifications is a quick way to maintain some control over the flow of information.

“Everything from every app is only designed to frustrate you,” Mercieca says. “They not only addict you, but they will withhold notifications from you so that you’ll keep checking back … and so it’s really distracting.”

She says if you plan to tweet or share information, think it through first.

“Think about who your audience is when you are communicating online and what your contribution adds to the conversation,” Mercieca says.

Written by Caroline Covington.