A 2014 Department of State Health Services report found almost three-quarters of Texas counties had no psychiatrists at all. That means Texans seeking mental health in these mostly rural areas often have to drive hours to an appointment – if they can get one at all. But a new program in Midland could offer at least a partial fix.

Driving west toward Texas’ Permian Basin, the tell-tale signs of oil country are everywhere. Highway shoulders are littered with shards of truck tire, and the vast, sandy landscape is dotted with as many pump jacks and power lines as small trees and scrubby bushes.

But Midland, a major hub of west Texas oil country, could also soon become a much-needed hub for child psychiatry. The demand for those services has grown along with the latest oil boom – as more families move to the area.

Now, the Midland Development Corporation is giving Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center $8 million. The money will train two new child psychiatrists per year in an effort to address the current severe shortage. Right now, families have been traveling to Dallas or San Antonio to get care.

Texas Tech Chair of Psychiatry, Dr. Bobby Jain, says the fellowship should get more kids appointments faster – similar to Texas Tech’s adult psychiatry residency program that started two years ago.

“Before the residency program, our waiting time was easily four months, six months to see us. We have reduced that waiting time to within a week or two,” Jain says.

This approach is one among many aimed at fixing Texas’ psychiatrist shortage – something that has hit rural Texas particularly hard.

In a phone call with Dr. Jain he said the fellowship should ultimately boost the number of child psychiatrists practicing in west Texas.

“Psychiatry fellows, when they train, they tend to remain in the area. So we can easily absorb at least 10 psychiatrists,” Jain said.

If that ends up being true, Midland-Odessa would triple its number of child psychiatrists – helping it to serve the entire region. Every other county in the area faces either a severe shortage or doesn’t have any child psychiatrists at all.

One part of Texas Tech’s fellowship will put psychiatrists where they may be needed most: local schools.

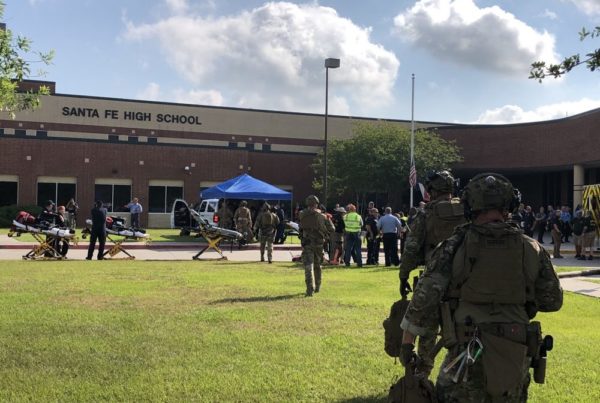

On a hot June morning, Ector County Independent School District Head Nurse Laura Mathew opens the door to her office at New Tech Odessa High School. She clears a large plastic bag of pink pool noodles out of the way to make room on a chair. The noodles had been cut to about the size of a human shin bone. They were going be used to practice making tourniquets in preparation for a school shooting.

“We’ve had, unfortunately, a lot of violence in schools throughout the country, and so, as we get to the root of some of those problems, a lot of that is stemming from mental health or the lack…of services,” Mathew says.

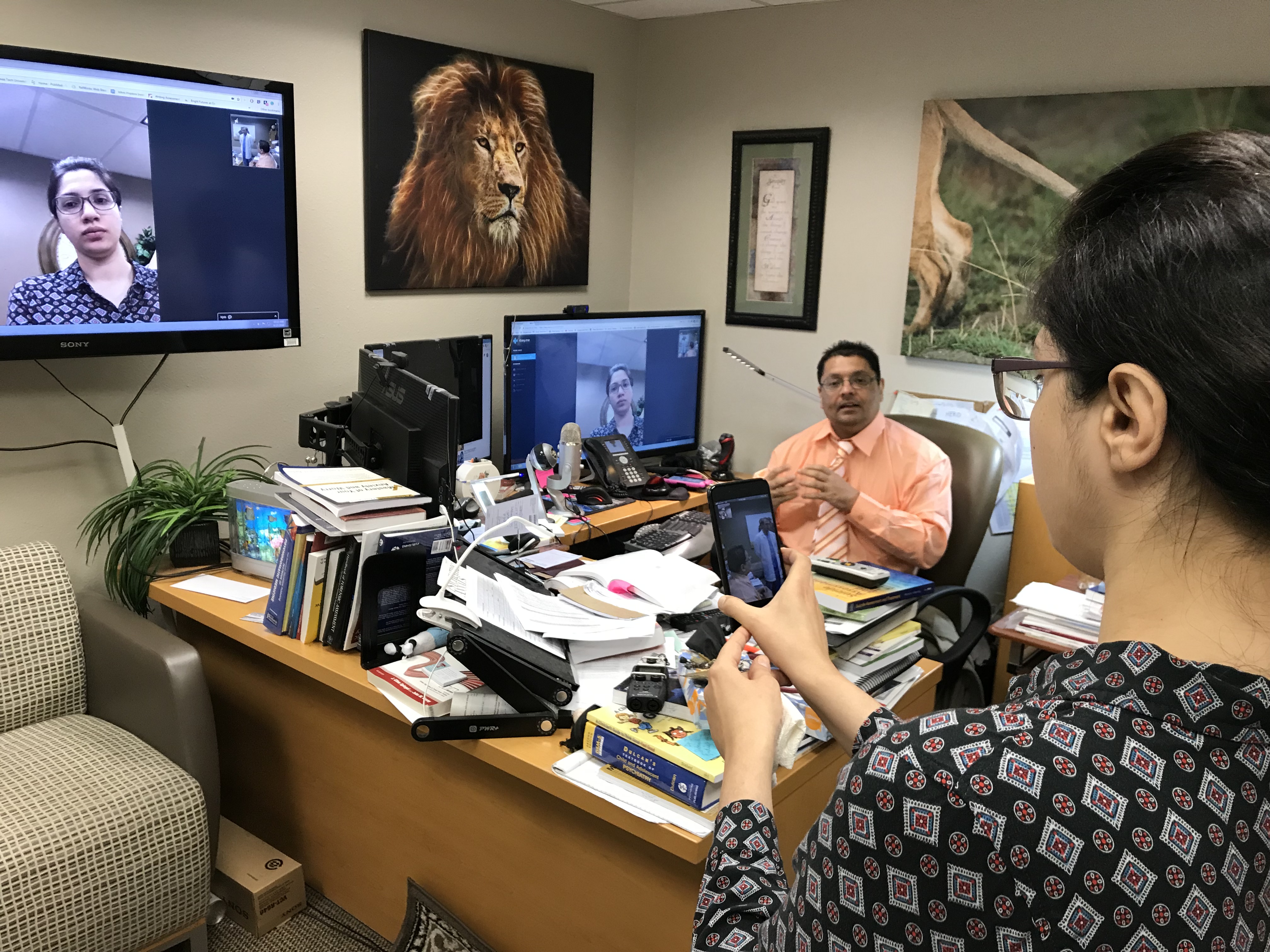

School violence, and just greater awareness about young people’s mental health, are driving demand for more robust services. Two years ago, Texas Tech’s Jain started a program where students could book telepsychiatry appointments through the school nurse. The new child psychiatry fellows will also be part of that program. Jain says they’ll be in the room with students during their virtual appointments with him.

School nurse Laura Mathew says 70 kids have used the program so far.

Annette Klinke is a nursing assistant at Ector ISD and has a middle-school-aged daughter who’s used it. She says it’s better than what she did before, which included traveling to Dallas.

“Dallas is just too far away, it’s a six-hour drive…it’s expense on top of time. And so I sought out…someone else that could manage us but because of our population and lack of help, it was a huge wait list,” Klinke says.

Klinke says her daughter likes the telepsychiatry, plus it’s convenient for both of them. “It’s been very convenient for parents because you just make one stop. You go to the school…or if the child is old enough, the child can go by themsel[ves].”

More and more, local psychiatrists who see patients in person are being replaced by telepsychiatry with doctors in big cities. Jain’s program is more of a hybrid of in-person and remote visits.

But over the next few years, as the fellowship gets underway, Jain is going to have to prove that the doctors who come to train in Midland will stay there. Some of Jain’s current psychiatry residents are from abroad, and through the J-1 visa program, they’re actually incentivized to stay in the area for three years after their training. But it’s not clear that recruiting international doctors is a long-term solution. Shelley Smith has experience with that with West Texas Centers, one of the region’s local mental health authorities.

“So, we had some great doctors through that J-1 visa program but what we found is as soon as that three years was up, they were gone,” Smith says.

Some rural health experts say the only way to increase the number of rural doctors is to recruit from within those communities. The University of Alabama has done this with its Rural Medical Scholars program, which recruits kids to go into family medicine starting in high school. Almost half of those students ended up practicing in rural areas, and its lead researcher, John Wheat, says two thirds of those stay in rural practices long term.

“A rural background has been shown to be the number one consistent factor in producing rural physicians.” Wheat says.

As for Texas, the state is counting on these new medical residency and fellowship programs to ease the shortage. A new psychiatry residency at University of Texas Health Science Center at Tyler just started last year, and the state is investing up to $2.7 million to make it happen.

It’ll be impossible for these new psychiatrists to fix the mental health care shortage alone, but with more of them, and the added help of telepsychiatry, they’re starting to fill in the gaps.

“If we can see a patient in person first, that usually helps us. But if the patient cannot be seen — if it’s a three-hour drive, four-hour drive one way and that’s stopping the patient from coming in to [see] us — then we[‘ve] got something available to the patient,” Jain says.

Support for Texas Standard’s ”Spotlight on Health” project is provided by St. David’s Foundation.