Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is in the news again.

In late July, a man killed four people and then himself in New York City in what investigators believe was an effort to draw attention to what the gunman suspected were brain injuries he’d sustained playing high school football.

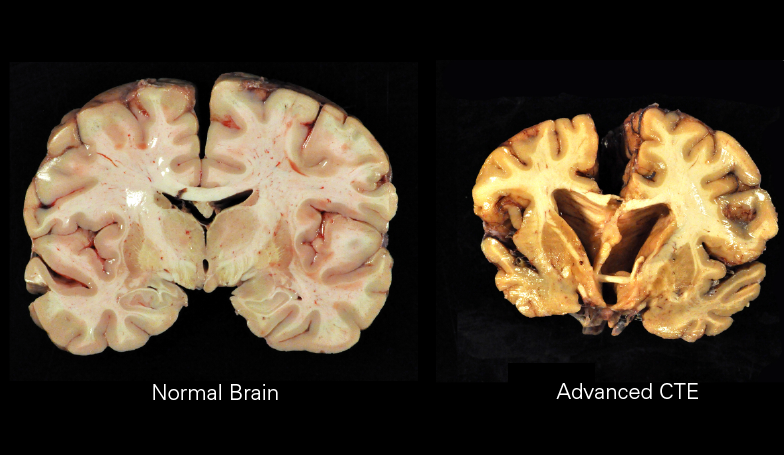

CTE is a disease that can currently only be diagnosed definitively when the patient is deceased, through a brain autopsy. And a new study warns doctors against straying from that.

Christian LoBue, a clinical neuropsychologist at UT Southwestern, led the study that is now published in “Neurology.”

Listen to the interview in the audio player above or read the transcript below.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: Is it true that one of your primary conclusions from this study is that doctors should refrain from diagnosing or even offering a probability that a living patient has CTE?

Christian LoBue: That is correct.

Regardless of what doctors, or even individuals, have in terms of beliefs about CTE and what symptoms can be related to it, we simply cannot identify any sort of presentation that can be directly tied to CTE.

Part of the challenge is, usually when individuals are identified as having CTE at autopsy, they don’t just have CTE – they have Alzheimer’s and other processes going on that could easily explain symptoms and problems.

The problems tend to be quite varied, ranging from changes in how they think to even changes in the how they act in certain situations. Well, as a clinician, we have lots of different ways we can treat those problems, and usually, many times, those problems can actually be reversed.

So doctors in the field, as well as individuals, shouldn’t be so tied to thinking that their problems are irreversible. They should seek help and try to address what those actual symptoms and problems are. Because receiving a diagnosis of something that is irreversible can lead to really profound changes in how someone thinks about their life.

And we’ve actually seen people that were diagnosed by providers outside of our institution and they had depression, sleep problems, things like that. We treated those, they got better. Did we treat CTE? Well, there’s no way to know if that person had CTE or not, but we treated their problems, and they certainly got better, and they did not demonstrate a neurodegenerative disorder.

Because patients often will present with concerns about memory and they don’t have a memory problem. They actually have a lot of things going on, maybe headaches, maybe they have a lot of stress in their life, maybe they’re not getting very good sleep. Those things are not brain conditions, but they can affect how someone’s able to think day to day. And if we can address those, we can improve how one is functioning.

» GET MORE NEWS FROM AROUND THE STATE: Sign up for Texas Standard’s weekly newsletters

Researchers have been studying CTE for over 50 years. Why don’t we know more about it?

Part of it is CTE is found to be much more rare than previously thought.

If we just look at aging studies, patients that are followed long-term in these large-scale research projects, we actually find very few of them actually show CTE, even if they had a history of head trauma and things like that. We don’t know a cause and effect.

The second thing is CTE hardly ever presents on its own. Usually when persons are identified as having it, they also have a lot of Alzheimer’s or other sorts of pathologies in their brain.

What would you say to someone who’s thinking, well, wait a minute, this sounds like an attempt to deflect attention away from CTE?

No, if anything, is to direct attention to CTE and really highlight what we know from the evidence and what we don’t know.

There’s no way anyone can definitively say they were to have it. And that can actually be very damaging if that’s all they focus on, because that’s going to, more often than not, prevent them from actually getting the help that they probably need – where we can actually address those other things that are treatable and reversible and improve their quality of life.

If individuals want to volunteer, participate in research to help us understand more about these things, that’s great. We need it. We need more scientific studies that are very rigorously done to understand these sorts of relationships.

We just don’t have good evidence at the current time to say it is or it isn’t.

If you found the reporting above valuable, please consider making a donation to support it here. Your gift helps pay for everything you find on texasstandard.org and KUT.org. Thanks for donating today.