Emelia Garza is not the main character in research papers about San Antonio’s red-light district. A description won’t even appear if you Google her name. But Garza altered the course of sex work in San Antonio, and historians have tried to understand why she doesn’t dominate the pages of that history.

Her life in the public eye started in 1889 when San Antonio passed its “bawdy house” ordinance, which allowed brothels to legally operate in the city — “legally” being the key word. Brothels existed before the ordinance and were labeled in fire insurance maps as “female boarding houses.”

Then-mayor Bryan Callaghan was inspired by other cities that enjoyed significant profits from vice industries, so he introduced the ordinance to city council with a plan to rake in money. This mayor was nicknamed “King Callaghan” and was somewhat of a political boss during this era.

Once the ordinance was in effect, the city immediately started charging brothel owners with hefty licensing fees — about $500 for a license in 1889. (That’s about $15,000 in 2022, according to an inflation calculator.) But San Antonio’s charter didn’t actually allow the city to require licenses on brothels, saloons or gambling halls. So, why would city officials introduce the ordinance if it was illegal?

It’s possible they looked toward other Texas cities — like Austin, Waco and El Paso — which had charters that allowed them to charge licensing fees, wrote history teacher Jennifer Cain in her master’s thesis while at the University of Texas at San Antonio. Perhaps San Antonio officials looked at these cities and assumed they could do the same, she added.

Either way, one San Antonio madam, Emelia Garza, refused to pay her fee and was arrested.

“She was basically required to pay a city licensing fee that, as far as I can tell, was even more money than the purchase price of the actual structure itself,” said David Carlson, Bexar County’s Spanish Archivist.

She challenged the city, and her case went up to Texas’ State Court of Appeals.

The case gained public attention, and the newspapers in town started following Garza’s story.

Dr. Lilia Rosas is a lecturer in the Department of Mexican American Latino/Latina/Latinx Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. She wrote her dissertation on San Antonio’s red-light district and dedicated a chapter to Garza’s court case.

“She did admit, ‘Yes, I do run a house of prostitution. Yes, I am a madam. No, I won’t pay for this license. And no, your license is illegal. And yes, I am going to seek counsel to fight this. So basically screw you,’” Rosas said.

Garza was right. While other Texas cities had charters that allowed them to enforce licensing on vice businesses, San Antonio did not.

“She stands out as the only Mexican woman who successfully — not only took a case to one of the highest courts in Texas — but actually won,” Rosas said.

The San Antonio Daily Express wrote an account saying they received a “special” telegram from Galveston when the ruling came down. A reporter went to Mayor Callaghan’s house to tell him the court ruled in Garza’s favor. The mayor didn’t believe the reporter at first and needed to be assured of the telegram’s “accuracy.”

Garza’s case was settled just two months after the bawdy house ordinance went into effect.

“This had to really stick in the craw of some people who had come to expect payment of those licenses. So any time you have somebody who disrupts a network that is generating a lot of revenue and a lot of money, you can typically expect there’s going to be repercussions from that,” Carlson, the Spanish archivist, said.

City council members voted to refund the money they had collected. Then, they had to submit a request to state officials in order to revise their city charter. Finally, they rewrote the bawdy house ordinance to legally issue licenses and charge fees. This took about a year-and-a-half — time wasted when city officials probably thought they would have already seen a profit.

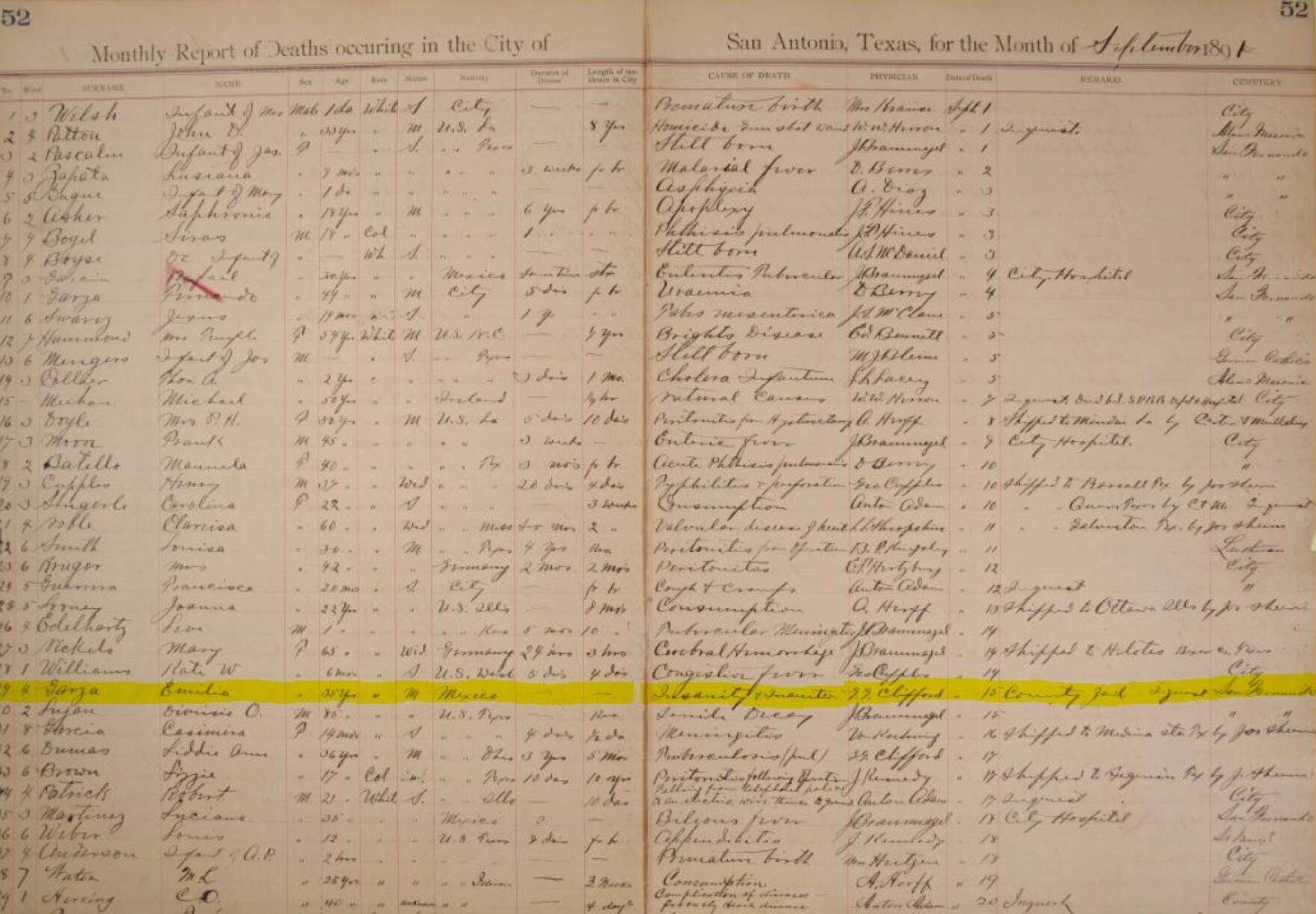

The second version of the bawdy house ordinance was passed July 20, 1891. Less than two months later — on Sept. 8 — Garza was declared insane by a jury of six men and put in jail. There isn’t a detailed explanation in the ruling of how or why Garza went “insane.”

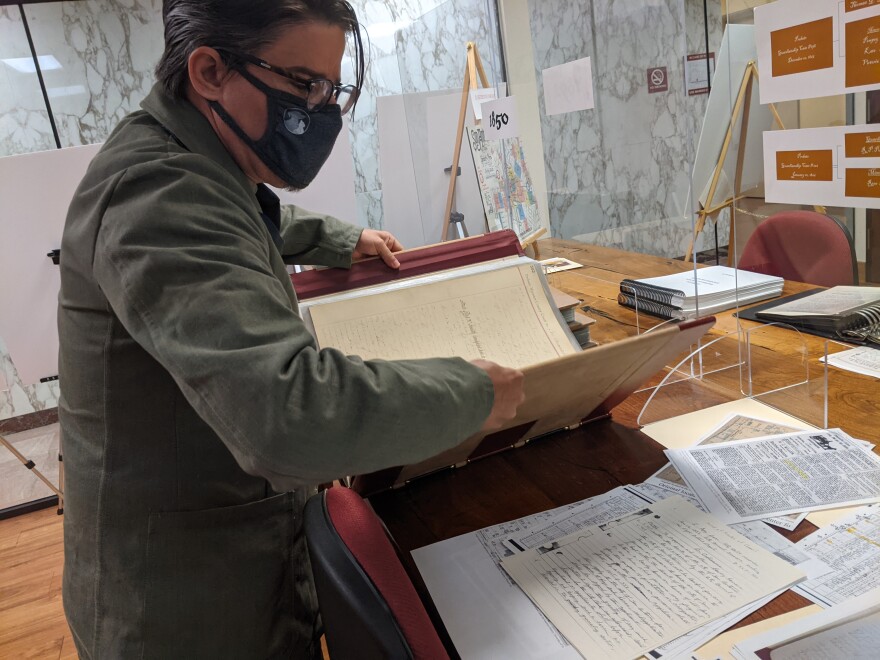

Carlson found the probate minutes where this decision was made by the jury of “good and lawful men.”

“They describe her as having had a quote, unquote ‘attack of insanity’ that had a duration of two days,” said Carlson. “But it’s hard to gauge given how it’s described.”

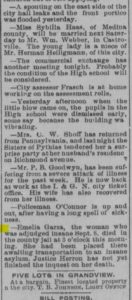

The San Antonio Light wrote an article titled “The Insane Woman.” It said Garza was leaving behind nice furniture, diamond jewelry, a piano and four children.

She was scheduled to go to the state asylum in Austin, but again, the court records don’t give examples or details of Garza’s insanity.

Cain — who wrote her master’s thesis on San Antonio’s red-light district at UTSA — now teaches U.S. history at Sandra Day O’Connor High School in Helotes and at Northwest Vista College in San Antonio. She never knew what happened to Garza after the insanity ruling.

“A great untold story of brothel owner Emelia Garza who boldly challenged city officials as a woman and as a prostitute, remains to be told,” she wrote near the end of her thesis.

Rosas expressed a similar sentiment. She added that during this time period any woman who was considered a nuisance could be declared insane. This was used, particularly, to control powerful women.

“For them to seek to not only discredit her, but to determine that she was insane, says to me, ‘Wow, what else were they worried that this woman was capable of?’” Rosas posed.

There were a few tricky obstacles working against the search to find out what happened to Emelia Garza. Namely, her name. “Emelia” was often misspelled even in official documents. And “Garza” was, and is, a very common surname in San Antonio.

Women historically haven’t been well documented in local records, especially if they don’t come from money or own property, according to San Antonio Public Librarian Debbie Countess. The library has a database of newspapers and city records, and since Garza owned her brothel, it was possible there might be a document on record.

“I would have bet, probably, there was a 20% chance that I would find something on this woman for you,” said librarian Debbie Countess.

If Garza was sent to the state hospital in Austin, the newspapers in San Antonio probably wouldn’t have kept up with her. Her story would have ended there.

“But I went ahead and I did a search and bam, there it was,” Countess said. “And I about fell out of the chair because it was exactly what we wanted to know.”

The San Antonio Light newspaper announcing Emelia Garza’s death on Sept. 15, 1891. Courtesy Debbie Countess/San Antonio Public Library

Emelia Garza never made it to the asylum in Austin. She died in jail, exactly a week after she was declared insane.

The San Antonio Light article was digitized, somewhat recently, in the library’s database. Countess said if TPR asked her to search for Emelia Garza 10 years ago, she probably wouldn’t have found anything.

Knowing Garza’s date of death helped find other details — like her entry in the Bexar County death ledger. It stated Garza died of “insanity.” Countess explained that was likely a euphemism for malnourishment or dehydration.

“I can’t believe that within a week you would die from that,” she said.

None of the sources TPR spoke with could say for sure how she died. The ledger stated there was an inquest into her cause of death. But the historians and archivists told TPR that records of that investigation couldn’t be found.

Carlson also wasn’t sure what happened to her at the jail. He found in the probate minutes from her trial that she was ordered to be restrained. He said he believes that could have meant a number of things given the time period: handcuffs, a weight placed onto the chest or being restricted in a straightjacket.

Garza was buried in the city’s San Fernando No. 1 Cemetery — a Catholic cemetery.

“You’d like to know more about that funeral, right?” Carlson posed. “Like who showed up? Who were her friends? What was her social network like? Who were her pallbearers?”

Carlson did more digging on Garza. He found an article written 17 years after she died. It was about a student also named Emelia Garza — same spelling — who came from “difficult circumstances.” The article praised the young woman’s academic achievements at her Catholic high school.

“You know, like everyone, I’m a sucker for a happy ending,” Carlson said. “And I had thought, you know, wouldn’t it be great if this was one of the children of Emelia Garza?”

It’s a nice thought: maybe her family thrived after her death. But San Antonio’s census from this time period was lost in a fire — making it near impossible to know anything about her descendants.

But with four children, it is possible she has living family members today — some who might still reside in San Antonio. If you think you’re one of them, email us at redlights@tpr.org.