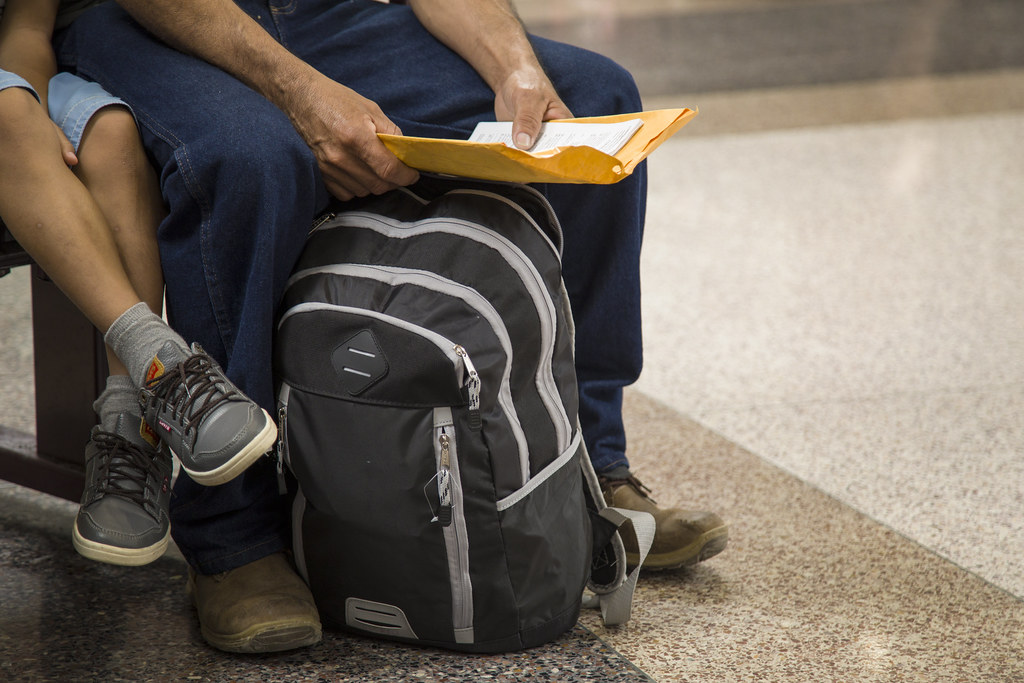

Over the weekend, officials of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, announced they would resume holding families at the Karnes County Residential Center outside San Antonio. And last week, the Trump administration reached a deal with El Salvador to send asylum-seekers there, instead of processing their claims in the U.S.

It’s all part of a comprehensive, multi-faceted approach to asylum and immigration, says Nick Miroff who covers immigration and homeland security for The Washington Post

Miroff says ICE had stopped holding families at the Karnes facility last spring in order to accommodate more single adults.

“They made a decision to hold single adults at that family facility in order to, in their mind, not lose control of the border,” Miroff says. “The fact that they’re going to resume detaining families there indicates that they’re starting to feel like they’re getting on top of the situation at the border.”

Miroff says immigration peaked at the southern border in May, with over 144,000 people crossing the border illegally. But crossings have dropped by as much as 60% since then, he says.

He says detention centers, plus the administration’s new deal with El Salvador, are all part of a “zone defense” strategy to deal with, and deter, immigration at the southern border. That includes: making some asylum-seekers wait in Mexico for their cases to be processed in the U.S; denying asylum to someone who failed to apply for asylum in another country en route to the U.S; and agreements with Central American countries to send some asylum-seekers to those countries instead of the United States.

“Any one of them could be blocked in court at any point, and they want to have a kind of diversified portfolio of enforcement strategies,” Miroff says.

The problem with the agreements between the U.S. and countries like El Salvador and Guatemala is that many people are fleeing from those very countries.

“These are some of the most violent countries in the world, and a lot of the people who are fleeing are fleeing from those circumstances,” Miroff says.

He says the potential of being sent to one of those countries could be a deterrent for many looking to seek asylum in the U.S.

“That, they think, will be something that would cause people to think twice about coming to the U.S. border to seek protection,” Miroff says.

He suspects that El Salvador agreed to the deal in order to protect the 200,000 Salvadoran nationals already living in the U.S. who have temporary protected status.

“Was there something in this deal that would provide a solution for those 200,000 people whose status is very much up in the air?” Miroff says.

Written by Caroline Covington.