Texas sign language interpreters are the latest group to join the Black Lives Matter movement in exposing racial disparities. In a statement released this week, the Texas Society of Interpreters for the Deaf, or TSID, acknowledged the field’s lack of diversity.

Nationwide, 87% of interpreters are white, while only 13% are people of color, based on a 2018 report.

“The interpreting community is heavily female and heavily white, as opposed to the consumers that we serve – deaf people – who are obviously of every race and of every gender. And so that disproportionality does a disservice to the deaf people,” said TSID President Whitney Douglass.

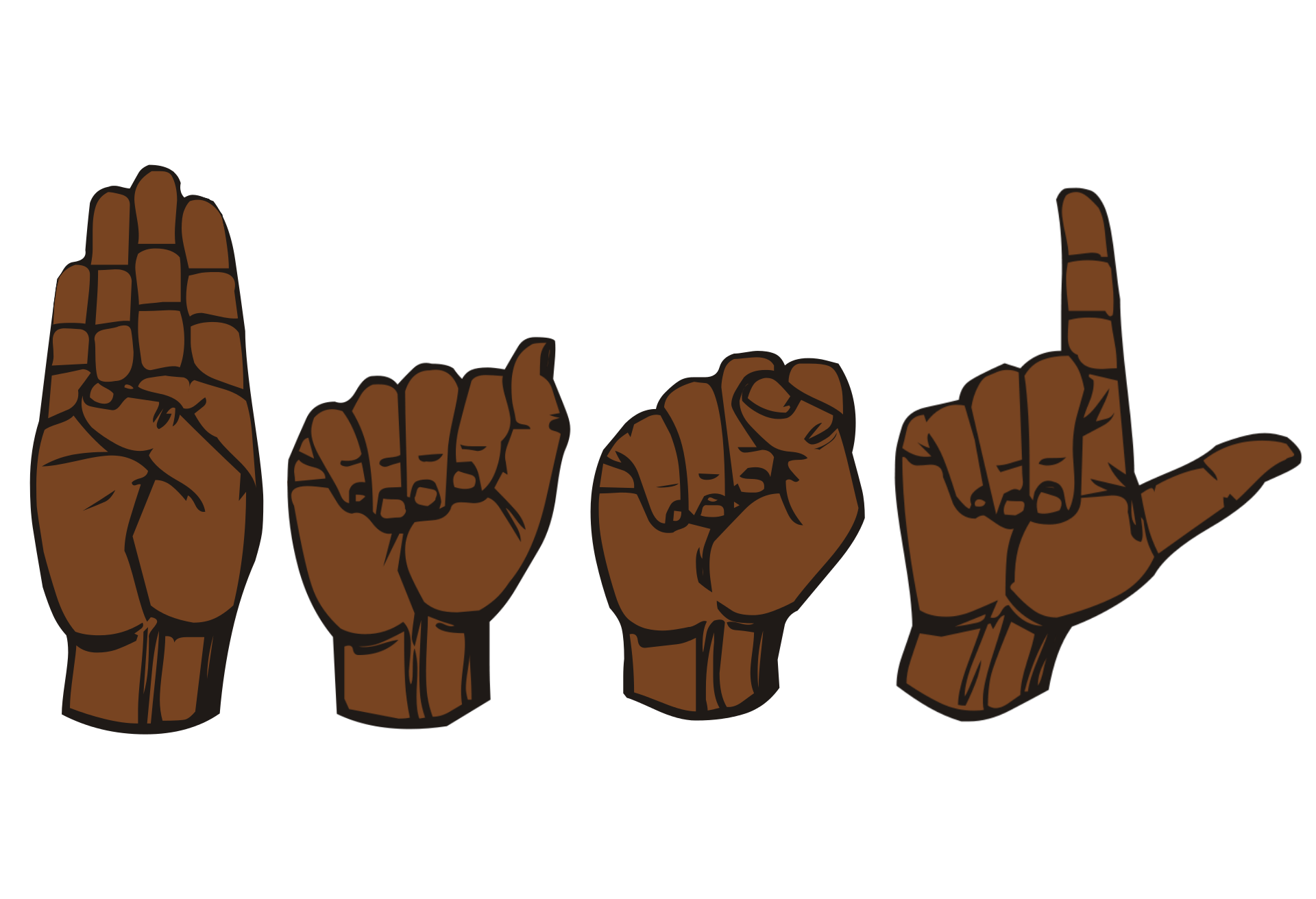

The different dialects within American Sign Language, or ASL, create a major communication barrier between white interpreters and deaf people of color. One of the most common dialects is called “Black American Sign Language,” or Black ASL, which first developed while schools for the deaf were still segregated. In Texas, schools for the deaf did not integrate until 1965 – 11 years after the Brown v. Board of Education U.S. Supreme Court decision outlawed segregation in public schools.

“Just having those separate schools before, I think, lent itself to the development of features of a language, of varieties of a language, that are slightly different than other features that are used at another school,” explained professor David Quinto-Pozos, who teaches linguistics and sign language at the University of Texas at Austin.

For example, to apologize in mainstream ASL, the sign is a closed fist to the chest with the palm facing inward. In Black ASL, however, it’s a fist to the opposite side of the chest, palm facing out. That’s the difference between the phrases “I’m sorry” and “My bad” in spoken English.

Growing up in Fort Worth, Texas, Pinky Collie said she only ever had two black, female interpreters – one in middle school and one in college. But she never questioned why her interpreters rarely looked like her. She just thought they were supposed to be white and rich.

“I was always misunderstood and underestimated growing up as a deaf, black girl, tomboy,” said Collie, who is now 34 years old and lives in Washington, D.C. “I try to voice more often when I am at a discomfort level with a particular interpreter, especially when they demonstrate my attitude, tone, and articulate vocal differently from my actual intention.”

Frank Peralez is part of the small community of Hispanic interpreters in Texas. When working with Hispanic deaf people, he said he can tell his clients are excited and relieved to see him for more reasons than just sharing a dialect.

“There’s a lot more meaning and a lot more impact when culture is shared between two people. And when you have a third party that’s trying to facilitate that community and create that bridge, it makes things harder and it makes things kind of sometimes awkward,” Peralez said.

To improve diversity among deaf interpreters, Peralez said the field should first improve access to education and testing for people of color, since most interpreting positions require a bachelor’s degree and certification test.

In its recent statement, TSID explored several ways to diversify the organization moving forward. Some of those ideas included waiving membership fees and conducting all of its business in ASL.