When the coronavirus reached Lubbock in the middle of March last year, the city’s public health director Katherine Wells and her team started a spreadsheet.

“A spreadsheet that was literally, like, a basic line listing,” she recalled. “Name, age, date of birth.”

Contact tracers added notes in one box. Had the person traveled? How long were they instructed to quarantine?

“That spreadsheet just kept getting bigger and bigger and bigger,” Wells said.

Creating her own spreadsheet to list data is nothing new for Wells. She said that the state surveillance system was out-of-date and not that helpful for local health department needs.

Then, as the virus spread in the community, contact tracing became more challenging. Wells said her priority was to count cases and track spread. Some demographic questions fell to the wayside – particularly about race and ethnicity.

“I know for historical reasons, it’ll be very important to see that,” Wells said. “But when someone has COVID, it’s like, we don’t care. We need to isolate and quarantine people, regardless of who you are.”

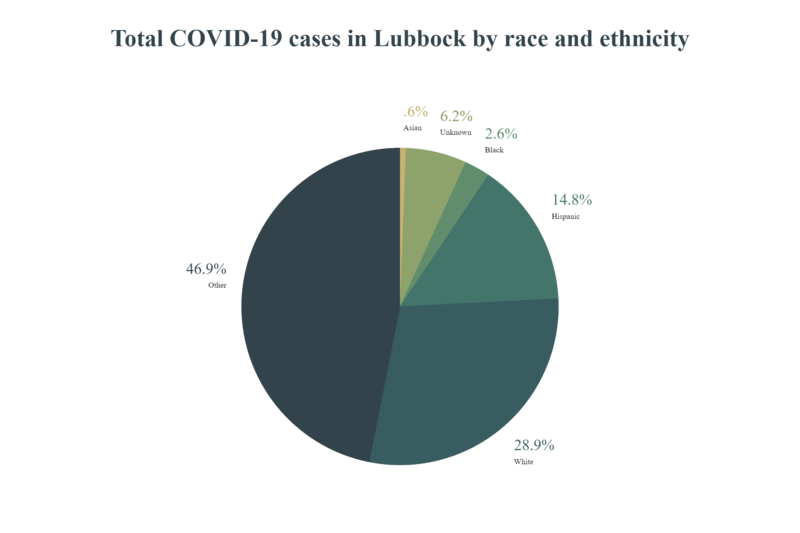

More than 48,000 people in Lubbock have tested positive for the coronavirus in the past year. Data from the county shows the race and ethnicity of more than half of those people is listed as unknown or other.

“I think it hurts the public trust part,” Wells said. “That I haven’t been able to say exactly what communities have been affected most locally. I haven’t had that concrete data that a lot of people want.”

Based on speculation and zip code data, Wells said she knows Lubbock’s lower income neighborhoods and communities of color saw the worst of the pandemic. That’s the case nationwide, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Still, Christy Martinez Garcia wishes there was harder evidence of that. She’s a local leader in the Hispanic community and the publisher of Latino Lubbock magazine. Martinez Garcia has seen the virus disproportionately impact her family and friends. She said she’s been to too many funerals this past year. It’s one of the reasons why she regularly asks city leaders about the missing numbers.

“Because that’s how we learn,” Martinez Garcia said. “That’s how we’re able to gauge. And so if we’re not keeping data, how can we learn from that?”

The one-year anniversary of the coronavirus pandemic has offered a look back at some grim milestones — from the earliest cases to the very first death associated with the virus. Health officials have been busy tracking the data, providing an important look into how Texans have lived so far and what comes next as vaccines give hope. But, there’s still some key race and ethnicity data missing statewide, according to the Texas Department of State Health Services.

Ben King, an epidemiologist and clinical assistant professor at the University of Houston College of Medicine, said years of underfunding and disjointment across Texas’s public health departments made collecting data hard, from the beginning of the pandemic. That was compounded by further misalignments at the federal level.

“Finding a way to actually capture that relied on departments that were completely overwhelmed with just simply counting,” King said.

He said race and ethnicity is the biggest hole in data that was partially collected and could have been remedied through case investigations. Though, he noted that health departments and contact tracers were working under crisis conditions with limited resources.

There are other questions he wishes were asked. For example, King said people of color, particularly Hispanic communities, often have multiple generations in one household. Tracking possible spread in that environment would be enlightening.

One identifier the state has been good at tracking is age. King said experts knew early on that older people were at a higher risk for serious COVID symptoms, so that data set is mostly complete. While it was predictable that race could become a factor in virus spread, due to cultural and medical predispositions, it wasn’t a top priority during initial data collection.

“The cynic in me said that speaks to the priorities we had at the time,” King said. “We knew that age was a priority, we knew that we needed to know how many people were testing positive. But there just was not a priority set, at any level I’ve seen, really, to capture race.”

Still, King said coronavirus data collection has improved since last year.

“The missing data is far better than it was before,” King said. “But will forever be an incomplete picture.”

Meanwhile, age played such a big factor during the pandemic that it led to older populations being one of the first to get the COVID-19 vaccine.

Race and ethnicity has not yet played a role in vaccine eligibility, but the state is now making collecting that data a priority.

“We have about a 20% unknown for race and ethnicity currently,” Imelda Garcia with the Texas Department of State Health Services said at a recent news conference. “However, we continue to see improvements and expect to see that number decline overtime.”

Lubbock has one of the highest vaccination rates in the state. But race and ethnicity data is missing for over a quarter of people who have gotten a shot. That’s improved after a change in data collection in February, when about 40% of vaccine recipients’ race and ethnicity was unknown. As people come to the Lubbock Memorial Civic Center vaccination hub for their second dose, Wells said workers are making sure that data is collected.

Have a news tip? Email Sarah Self-Walbrick at saselfwa@ttu.edu. Follow her reporting on Twitter @SarahFromTTUPM.