In Texas’ history it’s no secret that the life of a cowboy was fraught with danger. But the role the vaquero played in that history has often been minimized. For vaqueros in South Texas in the mid-20th century, life on the ranch was just as perilous.

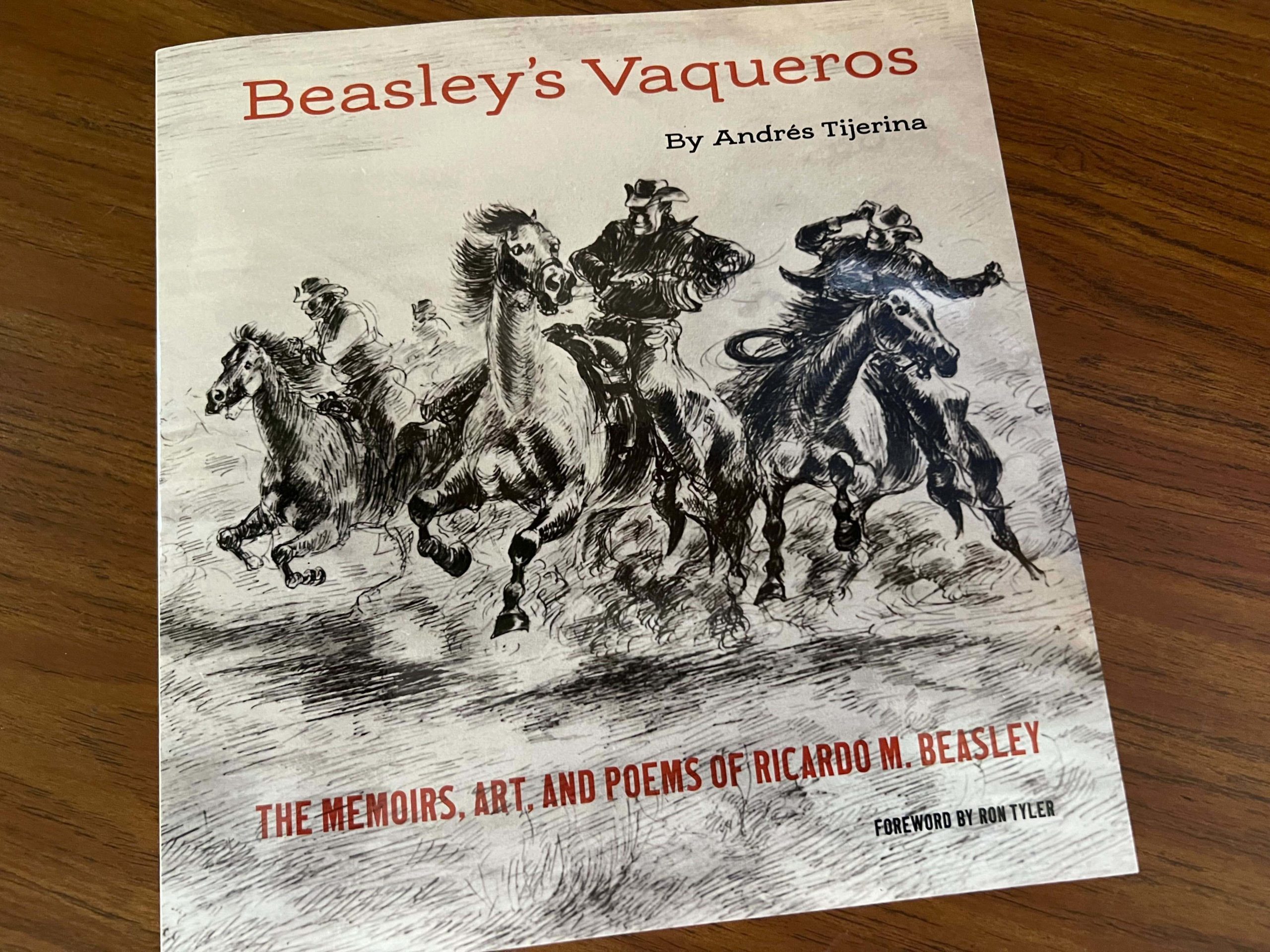

How do we know this? Because a young artist and vaquero himself, Ricardo Moreno Beasley, was there to capture these moments in ink, prose and poetry. Now, his life works have been collected by author, professor and historian Andrés Tijerina, a fellow at the Texas State Historical Association, in the new book “Beasley’s Vaqueros: The Memoirs, Art, and Poems of Ricardo M. Beasley.” Tijerina spoke with the Standard about Beasley, the moments he captured and why it was important to chronicle life on the ranch in South Texas.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: For those who don’t know, who is Ricardo Moreno Beasley? Tell us a little bit more about him.

Andrés Tijerina: Well, he’s an artist who lived in San Diego, Texas, and Duval County from 1908 until about 1994. And he literally was a vaquero – that is, a cowboy – out in the dense brush of South Texas around San Diego, which is halfway between Corpus Christi and Laredo. It’s halfway between San Antonio and Brownsville. It is the heart of the cattle industry of the 1800s. That’s where the Texas Longhorns came from. And he was a vaquero all of his life until he got to be about maybe 50, 60 years old. And the whole time he was doing art out in the field on a tablet that he had. So he is an artist who was a vaquero – that’s who Ricardo Beasley was.

He was, as I understand it, self-taught and, like many on a ranch during that time, didn’t go much past sixth grade or so in terms of formal education.

He went up to the sixth grade in a little bitty ranch town called Palito Blanco, which is maybe 10 or 15 miles south of Alice, Texas. It’s a ranch village, really, a little community. And he then continued drawing with no formal training at all, no schooling. And yet he became a prolific, eloquent writer and he became a prolific, elegant artist. The other thing about his education is that he read magazines and books on art. He evidently subscribed to art magazines of the time, because when I went to his old ranch home – which was so dilapidated, it had trees in the living room floor growing out of the floor, out to the outside window, and as you walked on the floor, you had to be careful not to go through the floor; I was able to walk into his ranch house – I saw a couple things.

One of them I saw on the concrete – they had laid a concrete sidewalk up to the front door – he did one of his drawings in the concrete, so his concrete is there forever. The other thing is that when I got to the kitchen, on the bulletin board, I saw not only notes to friends and relatives, but I saw magazines on the kitchen table. And there were magazines with stories about Eugène Delacroix, for example, these European artists. And so he does, in his tape recording that I have of him, he does indicate that he learned from them to express danger, high tension and stress in his drawings. So not schooled, but an educated man.

Tell us a little bit about his artistry and his style; it’s very unique. How do you describe it to others?

Well, the first thing I will say is that it is focused on the vaquero cowboy ranching life – that is, the wild steers, the animals, the horses, riding, roping. It is focused almost completely on that.

The second thing I will say is that while he did draw all of those scenes of the roping of a steer or whatever, he did it in a highly stylized manner. It’s much like you see in the drawings of Picasso, where Picasso will take a 3-D object and then draw it as a simple, very quick line – just one thin line. So some of the steers, for example, like a longhorn steer, the horns are not shown to be round, full, two-inches-in-diameter horns. They show to be nothing but a simple line, one simple, very highly stylized, but very beautifully, elegantly drawn. So that the animals and the wind and the bushes and the shrubs and the trees, etc., all are highly stylized. It’s not realism. You don’t see like it was a photograph.

Especially in U.S. popular media – you know, the movies, TV shows – the idea of Mexican or Mexican American cowboys have largely been absent. The representation just hasn’t been there despite the facts. And I’m wondering how you square that with what you see in the images and read in the prose and writing of Beasley. What was your takeaway as you lived this art, in a sense?

Well, as you say, we do not see the Mexican American artists the way you do see Remington and Russell and others, especially in Western life, which is, of course, the one major gift that Mexican Americans gave to the United States. The United States would not have longhorns, it would not have mustangs, if these people down in San Diego, Texas, had not bred the unique longhorn, the unique mustang. And then roping and boots and saddles and spurs – all that came from South Texas. It did not come from Mexico, did not come from Spain, did not come from North Carolina, South Carolina, England. It came from South Texas. All of the cowboy, all of the roping corral, the barbecue, everything that has to do with ranching is from South Texas – San Diego, Corpus Christi.

And yet very little art. Every once in a while, Remington or Russell or one of those Western artists would do one drawing of a vaquero from the waist up just to show his face in his hat. So you don’t have art of the vaquero. And this is the irony of it: The vaquero is the cowboy of the North America. He is the original cowboy. All the others copied him. Beasley knew this. He also knew that you don’t have books about the Mexican American. You don’t have artists; not until my generation came along in the 1970s do you even have people writing about Mexican American history. And we still do not have a history of Mexican Americans in Texas. He knew this. His whole community in San Diego knew that the Mexican American history has been intentionally, effectively silenced. And he, in his art, that’s what he was trying to do.

He was not trying to be a great artist. He said explicitly in his memoirs, “I want you kids to learn about the men of bronze who were like knights in shining armor.” So he wanted to fill the void of that unrequited gift that Mexican Americans have given, made to North America, to Texas. That’s what he wanted to do.

Correction: This story has been updated to correct the spelling of Eugène Delacroix’s name.