From the American Homefront Project:

As the Army renamed the last of nine bases originally named for Confederate generals, an entire category of memorials venerating the Confederacy disappeared.

The bases had been named for men who fought against the very Army that uses them, and who fought for the right to own slaves. The new names could scarcely be more different.

At the first renaming in March, Native American dancers and musicians were part of the ceremony as Fort Pickett in Virginia became Fort Barfoot for World War II Medal of Honor winner Van Barfoot.

Barfoot was a Choctaw Indian, which made it the first Army post in the continental United States to bear the name of a Native American soldier.

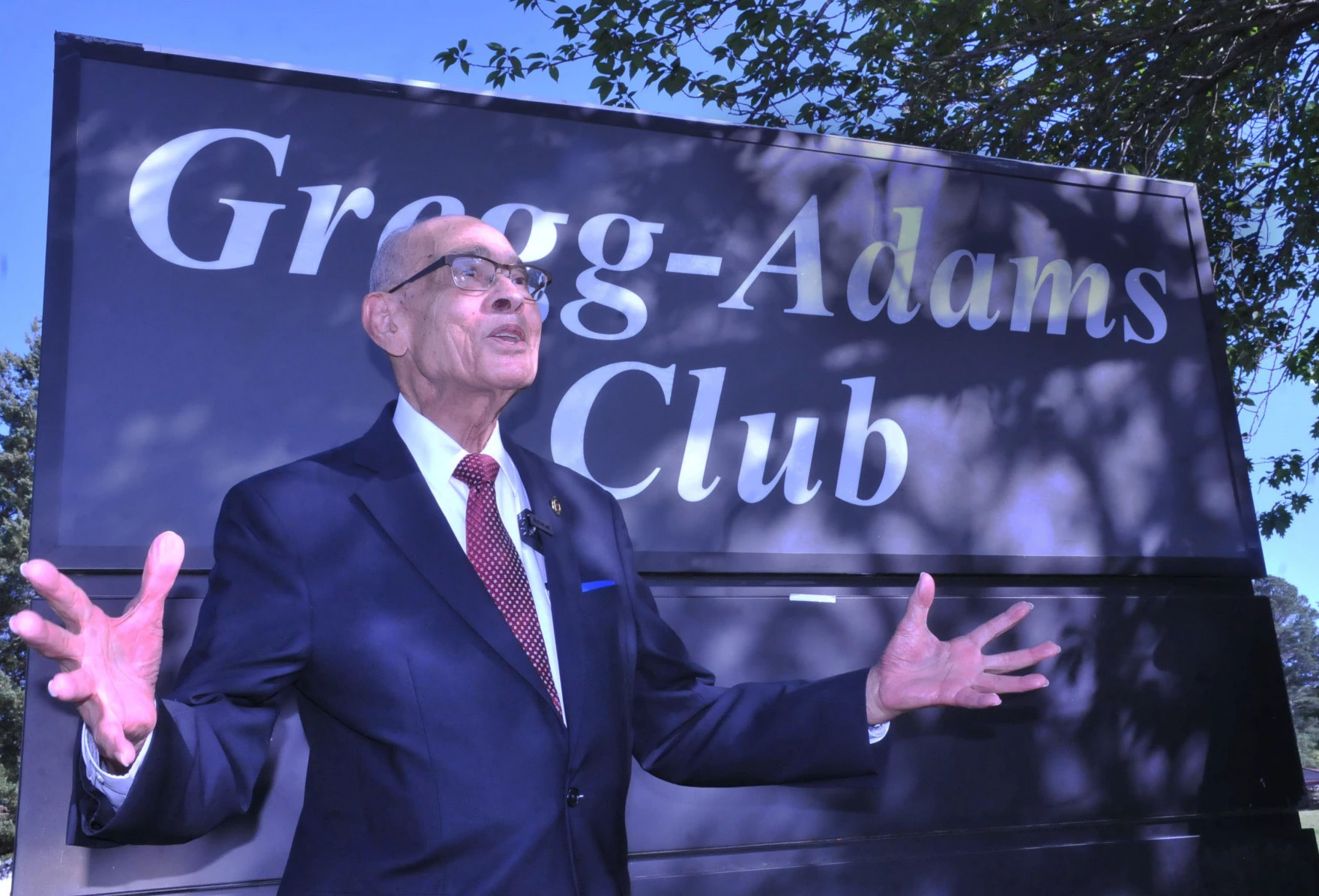

A month later, nearby Fort Lee was renamed for Lt. Gen. Arthur J. Gregg and Lt. Col. Charity Adams, both unusually distinguished Black soldiers.

Other bases were renamed for people like Dr. Mary Edwards Walker, a Civil War surgeon who was the first woman to be awarded the Medal of Honor, and Gen. Richard Cavazos, the first Latino four-star general and a hero of the Korean and Vietnam wars.

Now, in the final renaming, Fort Gordon in Georgia will be known as Fort Eisenhower for the general who planned and led the D-Day invasion and later became a highly-regarded president.

It’s a diverse group. People who did big things for their nation rather than against it.

Historians said the renamings – like the removal of many Confederate statues in recent years – are part of a national return to a more accurate understanding of the Confederacy.

Connor Williams, now finishing work on his PhD at the Departments of History and African American Studies at Yale University, was the lead historian for the federal commission that led the renaming process.

“United States soldiers had gone through this horrible conflict, which had killed more Americans than all of our other wars combined, and they were going to allow the Confederates back into the nation,” he said. “But they were very clear that the United States Army had defeated treason.”

“So by changing these bases, we’re we’re just getting back to the reality as it was in 1870, and 1890,” he said.

Around the beginning of the 20th Century, groups – notably the United Daughters of the Confederacy – began promoting the “Lost Cause” myth that made heroes of Confederate leaders and blamed the war more on Northern aggression rather than the Confederacy defending slavery.

They paid for hundreds of memorials to bolster their case, including statues of Confederate leaders placed in front of public buildings like courthouses.

As the effort to mythologize the Confederacy began gaining traction, the Army – as it rushed to build bases in World War I – decided to name those in the north for Union officers and those in the south for Confederates – preferably with short names to reduce clerical work.

Even if the Army’s decision-making on the base names weren’t directly part of the campaign to glorify the Confederacy, that doesn’t mean they weren’t a product of it, said Rivka Maizlish, a senior research analyst at Southern Poverty Law Center who works on its “Whose Heritage Project,” which is dedicated to to tracking and removing Confederate memorials.

“I think the fact that you could even use the names of people who made war against the United States of America for the cause of slavery and white supremacy for military bases shows the success of the propaganda campaign of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and other groups,” she said.

Maizlish noted that hundreds of Confederate memorials remain, many of them protected by recently-enacted laws in seven states.

“But it’s certainly a step forward to rename those bases,” she said.

Historians draw a distinction between the past — what actually happened — and “history,” which is how people decide to portray the past.

“What we think is more significant or less significant, what we think is more important or not, we always make those kinds of choices,” said University of Arizona history professor Susan Crane. “That’s how historians work, that’s how history gets taught… So it becomes a big, ethical, moral question, what are we choosing to pay attention to? And how does that reflect our values?”

Memorials, Crane said, are like history in that they are crafted to preserve and highlight a specific memory or meaning. And even those carved from granite aren’t the last word on the history of something.

“Everything decays and falls to dust eventually,” she said. “So just because it’s written in stone or made of stone doesn’t mean it’s permanent or needs to be permanent. It just means that was some of the hopes and intentions of the people that created it.”

Williams – the renaming commission historian – said the nation’s views about the Confederacy has shifted in recent decades, which he could see as he visited Army base communities to explain the history behind the old names.

“I was really impressed by how many Americans — North, South, aged, young, white, Black — were embracing this as a chance to really change the narrative,” he said. “I would give a talk to 75 people, two of them would make very loud and vociferous protests, but 73 would nod their heads or be okay with it.”