From Texas Public Radio:

An edgy outdoors art installation fascinated Austinites for more than two decades. Then a real estate deal brought it down.

Now though, there’s new life for one of the city’s quirkiest, most-loved pieces. Its odd little backstory starts with an artist named Ben Livingston who works particularly with light.

“And specifically with neon,” he said.

While he lives in Austin now, he wasn’t raised there.

“I hailed from Victoria, Texas,” Livingston said. “I’m a rare breed of South Texan, and I’m one of the few Jews, like fourth generation Jew, from South Texas.”

When he was a child his grandmother was assistant director at the San Antonio Little Theater, and she’d take him there often, where he built things in the scene shop.

“And I kind of learned how to build things that didn’t last, that looked really cool,” he said.

Like many artists he felt the need to create and developed a strong attraction to neon. Here in San Antonio, Fritz Ozuna had a neon business on Josephine Street that Livingston stopped in at.

He asked Fritz if maybe he could intern there, and learn neon. There was a near-constant stream of people who had asked Ozuna the same question.

“He said ‘I’ll tell you what, if you go to this school I went to in northern Wisconsin and do this workshop, come back and talk to me,’” he said.

Then a simple twist of fate made that possible.

“My grandmother died and left me 5,000 bucks and I went and did this,” Livingston said. “And the next time I saw Fritz, I walk in the shop, he goes, ‘What are you doing here?’ And I said, ‘Well, I just got back from Wisconsin.’ So I ended up apprenticing for him.”

In the next few years he lived in Washington, D.C., New York and Europe, but as is often the case for Texans, he wanted to come home. His significant other wasn’t so keen on the idea.

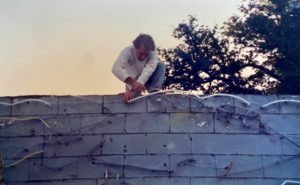

Ben installing the mural.

“My girlfriend insisted the only way she would come here is by way of Austin. So I’m one of the few Austinites that went there 38 years ago, kicking and screaming, but I’ve grown to love it,” he said.

Livingston established himself in Austin, and made a decent living making neon signs. But it wasn’t satisfying. He wanted to make art.

“I wasn’t born to make signs, and I could feel that pulling me.”

He needed a canvas on which to create that art. His business — ingeniously called Beneon — had a wall quite close to West 5th Street.

But…what to create? He got inspiration from an artist friend.

“And I had a friend named Terry Powell, very talented painter in San Antonio, and he had this great style and it was very childlike. It was like a child’s drawing of a house with a cat and a yard,” Livingston said. “And I borrowed or stole his, and this concept thinking that everyone responds to the fate of a child.”

So he had a style and a major element for the mural, and he was finally setting on what it needed to say. Problem was, the neon he knew how to do was either on, or it was off. He needed this piece to develop one section at a time. A computer guy named Frank Roberts had begun hanging around the shop.

“‘Frank, I’ve got a project, if you’re interested. I got something for you to do,’” Livingston recalled. “And he goes, ‘Oh, no problem.’”

This was in 1987 and computers were very rudimentary back then. Roberts had instructions for him.

“Just draw out on a Big Chief tablet what you want to see and how you want that to happen,” he said.

Livingston drew it out and Roberts sat down at his Macintosh to make the program. In a few days he came back with an animation program.

“It had this fixed sequence in it that would play at a certain time, just like a player piano would actually sound out a song,” Livingston said. “So I created this circle of life.”

That circle of life plays out like this:

“This 4-foot flower comes out of the darkness. And then this little house shows up, kind of Pee-Wee Herman, sort of little Astroturf yard with a scalloped sidewalk. And then it was like the moon and stars in space,” he said.

“And then the next sequence of the mural would be this jet rocket that’s flying over. And there’s like fire coming out of the tailpipe. And damn, if it doesn’t drop a bomb. The bomb drops down and it hits earth, the flower, and it blows up in this six sequentially animated mushroom cloud. It just blows up and undulates for a few seconds. And then the whole thing goes black,” he said.

And so, in a 54-second animated loop, the entire history of mankind plays out, with an apocalyptic ending. But wait. There’s more.

“And then the flower reappears and it plays all over again. And this cycle went on for 22 years,” he said.

News Reporter Jim Swift remembers seeing the neon play out.

“When I saw that thing on the side of the road, it was like, ‘Woah!’ It got your attention and it had a message, and it was art,” he said.

Swift did a couple of stories on Ben’s neon mural over the years. He reminds us that in 1988 the cold war was still going on.

“Back then, of course, the idea of nuclear warfare was still something that was on people’s minds,” Swift said.

Austin American-Statesman columnist Ellie Rucker caught wind of the piece and decided to do a story. And of course, she needed photographs.

“So she sent this guy named Smiley Pool, this young prodigy photographer from The Statesman,” Livingston said. “He’s a Pulitzer Prize winning photographer now. And he shot this thing and Ellie Rucker and the Statesman put this thing on the map.”

Pool remembers the experience fondly.

“It was one of the most fun photo assignments of my entire life,” said

Pool. “I remember being floored by the mural. I was just out there going ‘Wow,’” he laughed. “This is cool!”

In no time the mural went from obscurity to popularity. With all the positive response he submitted it for awards. And Livingston said he got a big one.

“It was an international lighting design award by the IES, which is the Illuminating Engineers Society,” he said. “And that sounds really nerdy, but it really is a very big deal, prestigious competition that a lot of people enter.”

He had a lot of competition that year. The lighting on a Bahai Temple shaped like a lotus flower. And that on the Philadelphia War Memorial.

“And then there was the Statue of Liberty. When we found out we won this award and they were a runners up, all of our jaws dropped,” he said.

In 1988, the Statue of Liberty’s lighting was runner up to Livingston’s 5th Street mural.

“We won an Oscar for a home movie, and it really was like that,” he said.

Thus began a two-plus decade period where people would come to view the mural at all hours.

“All night long they’d come by and it’s like sometimes they knock on the door thinking it was a bar,” he said.

It became an iconic part of Austin’s public art. But Austin is nothing if not constantly in change. In 2008 change came to West 5th Street.

“Someone bought our little building on Orchard Street, and I couldn’t have gotten kicked out by a nicer guy,” he said. “But he gave me time to get out and the neon had to come down.”

Livingston took the mural down and stored it. But as the years went by, what to do with it?

“And it got to a point where I thought, ‘Well, maybe I’ll just sell it piece by piece to people who would like a piece of Austin memorabilia,’” he said.

But Jim Swift convinced him not to, and there’s a good ending to this story.

Corrie Siegel is the executive director of the Museum of Neon Art in Glendale, California.

The museum has accepted Livingston’s neon mural, and will install it in the coming months. And just like its original installation, you won’t have to pay admission to see it.

“We’re hoping that when it is finally ready to be seen that it can be in the lobby of our museum and it will also be seen from the very busy Brand Boulevard,” Siegel said.

Livingston was floored when he was able to make this happen.

“It’s just this incredible success story that just came out of nowhere,” he said. “I don’t use the B word very often, but I feel very blessed about this.”

Livingston is planning to go to the Museum of Neon Art to help install the piece.