From KTEP News:

Under Gov. Greg Abbott’s estimated $10 billion Operation Lone Star, the number of DPS pursuits in this border city has nearly tripled.

According to an investigation by KTEP News, Department of Public Safety troopers initiated 140 vehicle chases from January through June 21st. There were a total of 55 pursuits and 10 collisions last year.

Of the 140 chases this year, at least 17 ended in a crash often resulting in injury. One person died.

KTEP obtained the pursuit and collision data with a Texas Public Information request.

Among the findings:

– On March 22, a DPS officer chased a truck carrying several migrants for nine minutes at a maximum speed of 100 miles an hour. The chase ended on an overpass when the driver crashed. The 35 year-old driver from North Texas, jumped off the overpass and died. A migrant from El Salvador also jumped and was seriously injured. Four other people in the truck were taken into custody by Border Patrol.

– On July 31, a DPS trooper chased a vehicle in far West El Paso. The chase ended with a collision with two other cars at S. Desert Boulevard and Redd Road. Nine people were hospitalized after the crash, six of those injured were migrants including a child. The others were bystanders.

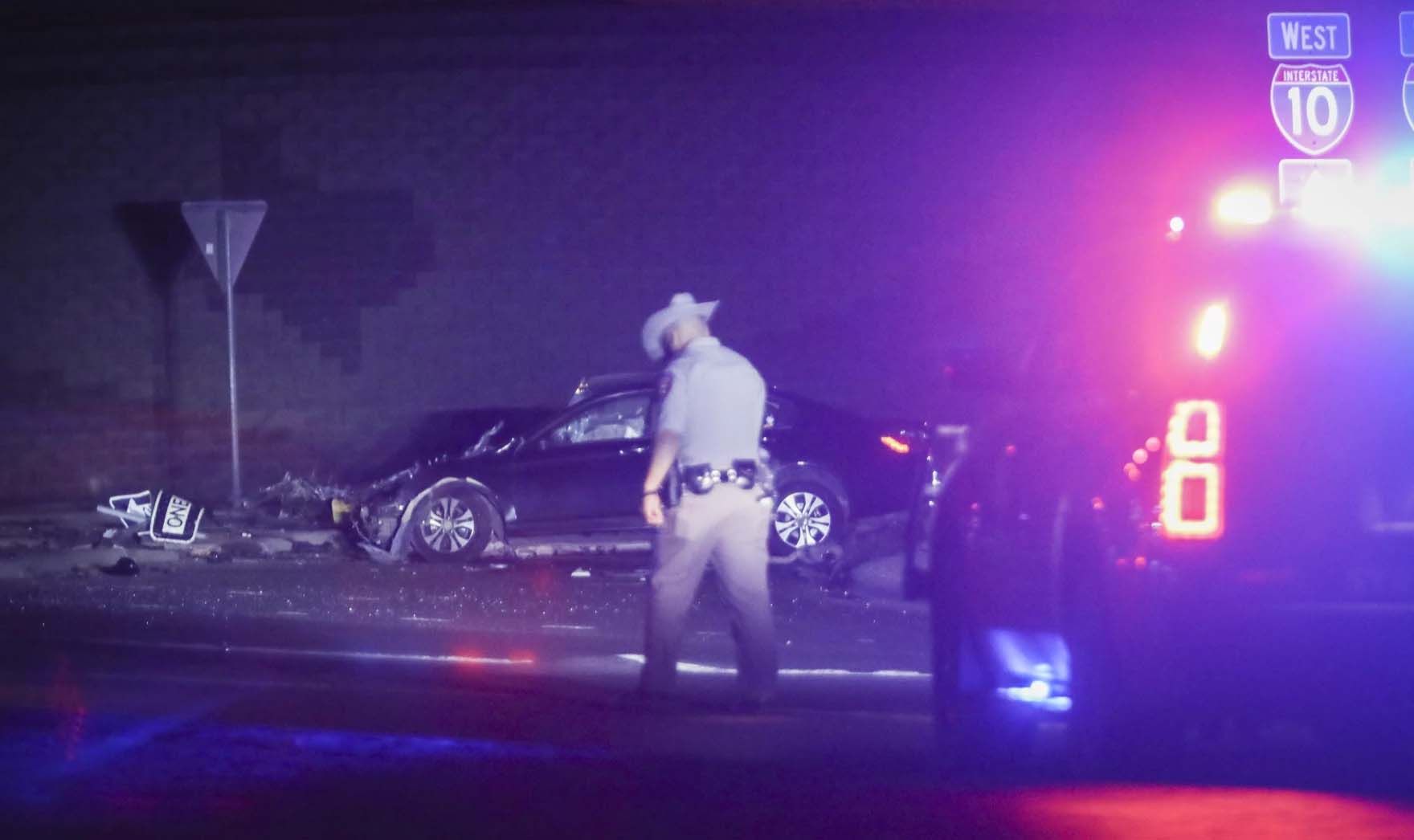

– On Aug. 9, a DPS trooper pursued a Dodge truck in far West El Paso after driver failed to pull over for a traffic stop. The chase ended with a crash at S. Desert Boulevard and Redd Road. Four people were taken to the hospital. Two migrants riding in the Dodge truck were among those injured. It was the second time in nine days a DPS pursuit ended in a collision at that intersection.

Abbott has long insisted that the state of Texas is working to “secure” what he calls “Biden’s open border.”

Lt. Elizabeth Carter, a spokeswoman for DPS, told KTEP News that the agency takes precautions to protect the public during pursuits. “We want to mitigate the situation as safely as possible.”

During a chase, troopers are required to inform a supervisor so they may “review and evaluate” each pursuit, according to the DPS manual. But “the decision of when to abandon a chase can only be made by the officer involved,” the manual states.

“Each of our troopers have been trained and they have the discretion to make these judgment calls,” said Carter.

DPS declined a request for a detailed interview about the pursuit policy and resulting collisions. The agency also did not provide information about the number of troopers assigned to El Paso County and the amount of Operation Lone Star funding spent along the border here.

On August 9, a DPS trooper pursued a Dodge truck in far West El Paso after driver failed to pull over for a traffic stop. The chase ended with a crash at S. Desert Boulevard and Redd Road. Four people were taken to the hospital. Two migrants riding in the Dodge truck were among those injured.

Aaron Montes / KTEP News

El Paso is the most populated county on the border and high speed chases can result in crashes in neighborhoods. The speed during a pursuit ranges from 60 to 133 miles an hour according to DPS data. Many of the chases ending in a collision reached speeds of 100 miles an hour or more.

Pursuits last a few minutes or go on for up to half an hour and the distance they cover can extend up to 20 miles.

One chase ended across the street from Alex Perez’s house in Central El Paso with a van crashing into a rock wall.

“I hope it doesn’t happen again,” he said.

DPS requires troopers consider several factors before chasing a suspect including population density, road conditions, weather and visibility. The type of crime and whether a suspect can be apprehended later are also weighed into the decision to pursue.

James McLaughlin, executive director of the Texas Police Chiefs Association, said most law enforcement agencies require supervisors to be involved in decisions to continue or end pursuits.

“The supervisor should be aware of the dangers,” he said. “If that supervisor, if he or she determines that the pursuit needs to be called off, they would. If not, they wouldn’t.”

McLauglin said the surroundings should factor into law enforcement’s decision to pursue a suspect on the road.

“You need to be aware of everything going on around you. Above and below. Backwards and forwards so you can react to something that is not going the way that you’d like it to.” McLauglin said.

In January, Border Patrol changed its pursuit policy in January acknowledging “vehicle pursuits do inherently pose risk – to members of the public, officers and agents and those in a vehicle being pursued who may not be willing participants.”

In El Paso, the city changed its policy in 2021 and requires officers to demonstrate a “clear and immediate threat to the public” to justify engaging in a high speed pursuit.

The American Civil Liberties Union has called on the U.S. Department of Justice to investigate Texas’ Operation Lone Star. The civil rights group filed a complaint last year citing at least 30 deaths and 71 injuries related to DPS chases near the border. It also alleges DPS traffic traffic stops disproportionately target Latino drivers.

This year the Border Network for Human Rights in its annual report on alleged civil and human rights abuses included concerns about DPS troopers.

“We are asking legislators to create some sort of commission to bring about accountability to DPS,” he said. “It is a rogue agency.”

Garcia calls Operation Lone Star “political theater,” pointing out the number of migrants crossing the border has sharply declined since the lifting of Title 42 in May.

He says border security is the job of the federal government not the state.

The Texas Public Safety Commission oversees DPS. The governor appoints the five members for six-year terms.

El Pasoans have watched the increasing number of high speed chases with growing concern. Several have resulted in injuries to bystanders including two this month near the same access road just off Interstate 10 in the Upper Valley.

Servando Hernandez, lives in a neighborhood near the Texas, New Mexico state line that has been the scene of several high speed chases.

“I’ve seen these types of accidents and they are very dangerous,” he said.

He says drivers shouldn’t evade the law, but the high speed pursuits put everyone at risk.

“For those of us who are driving, you or your son, or someone in your family could die because of a serious accident.”