Over the summer, Texas was in the national spotlight for the tens of thousands of unaccompanied Central American children crossing the U.S.-Mexico border.

It’s not a new phenomenon.

Two years ago, Dilcia M. Asencio Mazariegos escaped her brother’s violent domestic abuse in Guatemala. With a family member, Mazariegos traveled by bus through Mexico and slipped across the Rio Grande on an inflatable raft with coyotes.

“We went across with men who were tattooed,” Mazariegos says. “They looked like they had been drinking and were on drugs.”

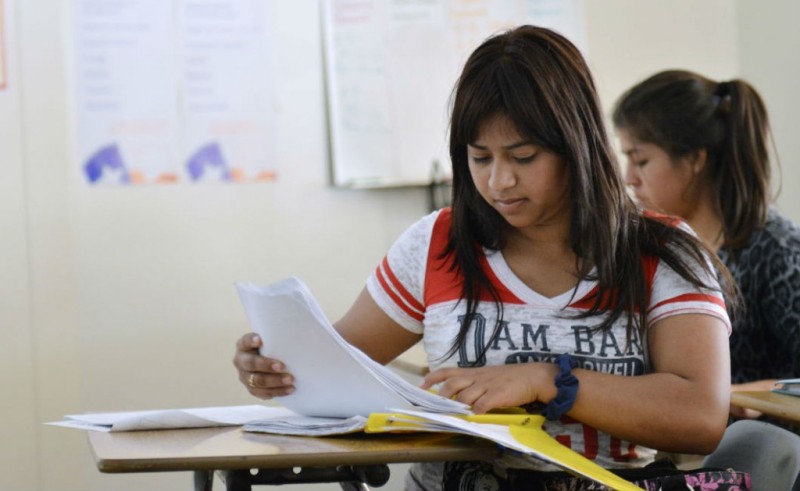

Border Patrol picked up Mazariegos on Christmas Eve, 2012. She then spent three months in a shelter before a family member paid for her flight to north Texas. Now, the 18-year-old is safe at Plano East Senior High, taking English classes.

Vincent Frost, one of Mazariegos’ tutors, says what she lacks in education, she makes up for in hard work.

“Dilcia’s incredibly sharp, she’s a very pragmatic girl and she learns pretty quickly,” Frost says.

On top of her classes, Mazariegos works two jobs — up to 40 hours per week. That work ethic is more often the norm than the exception, according her immigration attorney Paul Zoltan.

“She wants to be a productive member of society,” Zoltan says.

“She was eager to finish her studies — and I mean finish her studies, not drop out — in order to give back to those family members who’ve supported her.”

Mazariegos was approved for Special Immigrant Juvenile Status, which applies to cases where immigrant children have been abused or abandoned. That means she has a Green Card, permission to work and just received her Social Security number.

“Dilcia is one of the fortunate few to qualify for something other than asylum,” Zoltan says. “It’s through that program that she’s attained residency.”

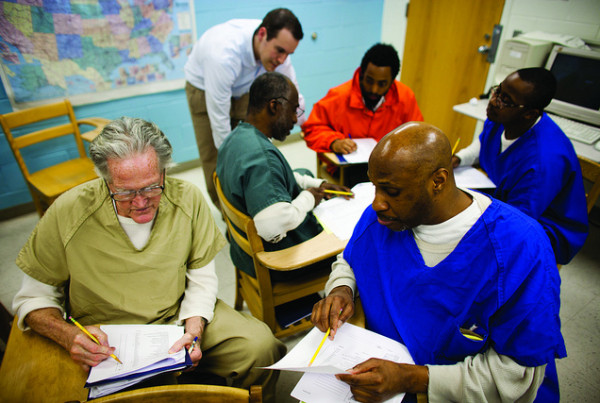

In Texas, one in three children has a parent who’s an immigrant or is an immigrant themselves. They have to learn a new language, adapt to a different culture and try to fit into a community that may not embrace newcomers, all while trying to make ends meet.

“Yeah, it’s difficult, but it’s for a reason,” Mazariegos says. “Every sacrifice leads to a reward. I’m one of those people who believes that to have a good future you have to work when you’re young, that way you don’t have to depend on anyone when you’re older.”

KERA’s American Graduate: Generation One series follows these first-generation Texans and the educators weaving them into the American tapestry. We’ll be featuring their stories, all this week on Texas Standard.