Heavy rainfall from Tropical Storm Beta has led to street flooding across Houston. COVID-19 remains a major health and financial concern for many people. And the federal government has ordered a moratorium on many evictions across the country.

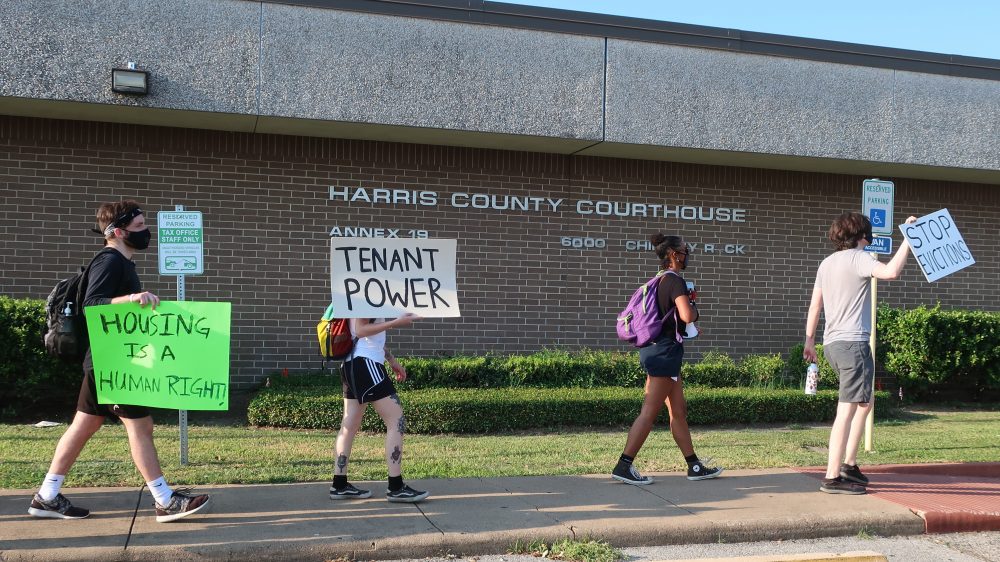

Despite all of this, Houston-area housing court judges are moving forward with evictions.

With 600 eviction cases on Harris County court dockets this week, renters, landlords and judges are continuing to grapple with how to navigate the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention national eviction moratorium that went into effect over two weeks ago. The Texas Supreme Court has stepped in to offer more rules but it’s still unclear if people who could lose their homes will be protected.

On Tuesday, with Harris County officials warning residents to stay off the roads due to the potential flooding impacts from Tropical Storm Beta, some courts remained open, including Justice of the Peace Lincoln Goodwin’s court, where 74 eviction cases on the docket moved forward as scheduled.

Houston leads the country in the number of evictions since the pandemic began. Houston-area landlords have filed more than 11,000 cases since mid-March, compared to just more than 500 in the Austin area, according to data from the Eviction Lab at Princeton University.

With no state or local protections in place, a national eviction order from the CDC promised some relief for Houston renters.

But after the CDC order came out, Houston At-large Council member Letitita Plummer said her elation quickly turned to frustration when she realized it wouldn’t stop all evictions in Harris County justice of the peace courts.

“The JP courts specifically are really making decisions based on their own mindset for every individual case,” Plummer said, “which really makes it difficult especially because a lot of people don’t really know what their rights are and so they can’t challenge whatever the decision is made in court.”

A Houston Public Media review of about 100 eviction cases found only one eviction was stopped by the CDC moratorium during the first week the order was in effect.

Plummer planned to bring an ordinance to Houston City Council to make sure renters had all the information they needed.

“We’re all waiting for someone else to give us the answer,” Plummer said, “and we have a lot of control in our own municipal government to make some solid decisions.”

When the Texas Supreme Court issued an emergency order addressing a lot of the gray areas she had pointed out, Plummer decided not to move forward with her proposed ordinance.

Renters and landlords weren’t the only people hoping for clarity. Harris County Justice of the Peace Jeremy Brown said he had questions about how to apply the moratorium in his court.

“One of the things that I was wrestling with before the order was, how much information should I give to tenants who come through the court about the CDC order,” Brown said.

The Texas Supreme Court answered that question: Judges can tell renters in the courtroom about their rights under the CDC order, though they’re not required to do so.

In order to be protected under the moratorium, renters must send a declaration form to their landlords stating their eligibility, or else the eviction can proceed. Renters must make less than $99,000, or have received a stimulus check, and they must have lost income as a result of the pandemic.

Under the Texas Supreme Court’s emergency order, now when renters get a written citation from a local court, it also has to include information about the renter’s rights, a link to legal help, and a copy of the declaration form to stop the eviction.

“Now on our new citation, it specifically is going to have information about the CDC order,” Brown said.

The new guidance could help many renters, but Brown said the majority could still fall through the cracks since most renters facing eviction don’t engage with the legal process — last year, 60% of renters didn’t show up at his court for their eviction hearing. Many renters leave as soon as they get a notice to vacate, particularly if they’re afraid to get involved with the legal system.

Other large states like New York, California and Illinois have their own statewide eviction moratoriums in effect, so the CDC moratorium has less of an impact. Brown said he would have preferred it if the Texas Supreme Court had issued a statewide moratorium last week, instead of simply clarifying guidance on the CDC order, but he wasn’t surprised.

“Texas treats housing as a commodity,” Brown said. “And when you treat housing as a commodity more so than an actual right, a guaranteed right, these are the collateral consequences.”

Meanwhile, others worry the latest Texas Supreme Court order actually could make it harder for renters to stop their eviction. Under the national CDC order, a renter has to give a signed declaration form to their landlord. Now in Texas, a renter also has to file that form with the court, at least in cases where an eviction lawsuit is already pending or has been filed.

Dana Karni, managing attorney with Lone Star Legal Aid, said that creates a new obstacle for renters.

“We have evidence of that because of the low percentage of tenants who participate in their own defense and certainly the absymally low number of tenants who are represented by counsel, where the concern is that tenants will not know how to file the declarative statement into the court record,” Karni said.

Karni and others said there’s still a lot to clear up as Harris County courts move forward, including how to enforce any criminal complaints if landlords violate the CDC moratorium.