In part 2 of our series on the impact of West Nile, we look at reducing the risk of the virus.

Eighty percent of people infected with West Nile virus never have symptoms, so that’s a big reason confirmed cases are lower than actual infection numbers. But even of those who do seek medical care with serious symptoms suggesting West Nile, less than 40 percent of adults and only a quarter of children are ever tested for it.

That’s according to research done by a team including Dr. Kristy Murray. She studies insect-borne diseases at Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston. She says many doctors choose not to test for West Nile because it has no specific treatment or cure. But Murray says forgoing a diagnosis may put others at risk.

“If we know what kind of cases we have, then we can go in and do mosquito control, prevent other people from getting sick, doing what we can to educate people around where that person contracted the illness so that they can be warned that there’s a dangerous virus in the mosquitoes in their area. So, on the public health side, it’s actually critical for us to know,” Murray says.

Rosalee Kibby is also pushing for more testing. Her 13-year-old grandson Cody Hopkins died within days of getting sick with West Nile in 2016. She told experts at a recent meeting of the state’s Task Force on Infectious Disease Preparedness and Response how hard it had been to get her grandson diagnosed.

“Cody was in the hospital for two days, and my son-in-law, who’s a vet tech for equines, is the one that recognized the symptoms of West Nile. And the doctor argued with him and said there’s no way he has West Nile. And then it took three more days to get the tests back. So Cody was in a coma for five days and he finally passed from a heart attack,” Kibby says.

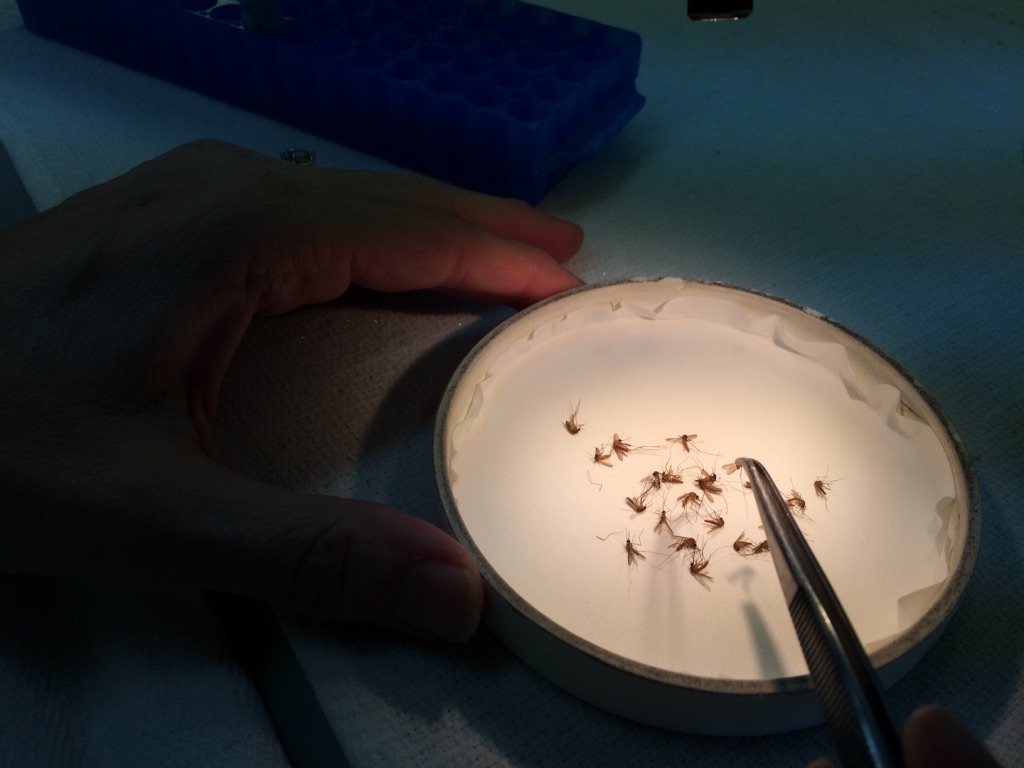

Human illness is one way we find out about West Nile; testing mosquitoes is the other. But that information is also very incomplete. Currently, in Texas, only about 55 of the state’s hundreds of cities and counties collect mosquitoes and submit them to the state for testing. Just a handful of jurisdictions do the procedure themselves. Bethany Bolling is the microbiologist in charge of the state lab that tests for West Nile and other diseases.

“Ideally, we would like to get them from every county so that we’re doing surveillance. The idea is we would detect viruses in mosquitoes before they are detected in humans. We want to avoid human cases,” Bolling says.

While the lab also tests mosquitoes for dengue fever, Zika and several other diseases, Texas Department of State Health Services spokesman Chris Van Deusen says the program has the greatest potential to prevent West Nile transmission.

“Of the common mosquito-borne diseases in Texas, it’s the one you’re most likely to find in mosquitoes before it gets to people. So that’s why the surveillance for West Nile is particularly important because it really can be an early warning that lets jurisdictions educate the public or do some kind of integrative mosquito control,” Van Deusen says.

There’s no requirement that cities or counties monitor mosquitoes for disease, even if residents contract West Nile. But Van Deusen says the state provides training and assistance for those that want to participate.

Meanwhile, attempts to develop a West Nile vaccine for humans have so far not borne fruit. That frustrates Dr. Murray, who sees people every day whose lives have been devastated by the disease.

“It permanently impacts their lives and you see people who are paralyzed. We’ve done studies looking at the brain, you know, how much the brain doesn’t recover from infection, and we can actually see the brain get smaller in size afterwards because it’s basically like having scar tissue because you have this traumatic assault to the brain,” Murray says.

A drug being investigated by the National Institutes of Health seems promising and could prevent a slew of diseases, not just West Nile. The vaccine, currently known only as AGS-v, works to reduce the body’s allergic reaction to mosquito saliva – that itching and swelling you experience with a bite. That matters because that allergic response impedes the anti-infection response your body would otherwise mount. Dr. Matthew Memoli is leading the current research into AGS-v.

“Instead of developing a purely allergic response like you do normally to a mosquito bite, you would develop less of an allergic response and more of an anti-infection response when you get bitten, so that any organism that is present would have a harder time causing an infection,” Memoli says.

Considering how many diseases mosquitoes carry, it’s easy to see how such a vaccine could be a game changer. But the drug is still in the earliest stages of testing. And even if it does prove successful, the entire process of assessing its safety and effectiveness will take years.

In the meantime, improved reporting and surveillance could help, along with simply trying to avoid mosquitoes whenever possible. As Dr. Murray reminds us:

“All it takes is one mosquito bite from an infected mosquito and your life could be permanently changed from that point forward.”

Support for Texas Standard’s ”Spotlight on Health” project is provided by St. David’s Foundation.