From KERA:

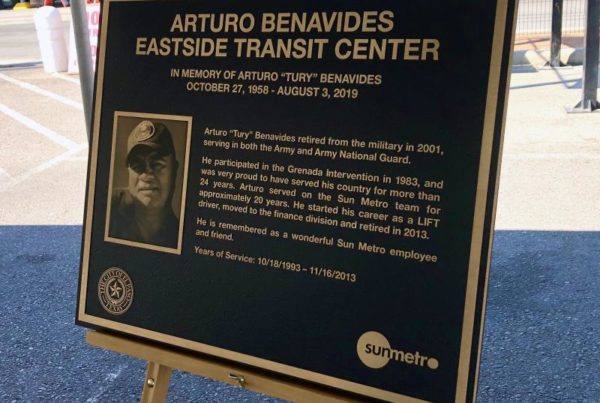

One year ago, police say 21-year-old Patrick Crusius opened fire on shoppers at a Walmart in El Paso, killing 23 people in what would be the deadliest attack against Latinos in recent American history.

Many believe the suspect developed his extremist views online, but the changing face of the North Texas county where he grew up may have also influenced him.

It wouldn’t be right to describe the community where Patrick Crusius grew up as a “small town.” In 2019, Allen had a population of north of 107,000, up 547% in the last three decades. Allen sits in the middle of one of the fastest-growing counties in the country. Collin County’s population has doubled over the past two decades, topping 1 million. Two of its cities, Frisco and McKinney, were among the fastest‐growing large cities and towns between 2018 and 2019.

Still, driving through the sleepy neighborhood Crusius once called home — seeing the manicured lawns, the large trees and the strangely uniform aesthetic — it’s easy to understand why the area’s often described as simply a northern suburb of Dallas.

But the fact is Collin County is no longer just a residential community within commuting distance. The cities north of Big D are booming. Companies and new residents are moving to Plano, Frisco, McKinney and Allen so quickly the Texas Demographic Center estimates Collin County will have 2.4 million residents by 2050. Other estimates put the county’s 2050 population as high as 3.5 million.

The thing many outsiders haven’t noticed is the surge in its nonwhite population. In just 20 years, the Texas Demographic Center said, Collin’s Black and Asian populations have more than doubled. The Hispanic population has expanded from 10% to 15% of the county. In all, 45% of Collin residents today are people of color.

This phenomenon was noted in the so-called manifesto Crusius published online 20 minutes before he entered the Walmart near the Cielo Vista Mall in El Paso. “This attack is a response to the Hispanic invasion of Texas,” the online screed said.