Parish Hirasaki was not planning on being a scientist. At least, not when she first got to Duke University.

“I was sent off to college to find a husband,” Hirasaki says. “And to get a teaching degree so if god forbid anything ever happened to that husband I could work when my children were in school. So that is the era I came from. “

The year was 1963. And as Hirasaki tells it, that’s what most women did… if they had the opportunity to go to college at all. But once she reached college, Hirasaki quickly realized teaching wasn’t in the cards. She struggled with the liberal arts courses. But she had always been good at math. So she changed her major.

But somewhere along the line I got interested in working in the space program,” Hirasaki says. “And thought, ‘Gee, maybe I can be an astronaut one day.’ And I think if most people back then who went to work in the space program fess up, that’s what they were thinking, too.”

Hirasaki did not become an astronaut.

Instead, she worked as a heat shield specialist for the Apollo 11 mission. Her job was to make sure that the lunar command module could withstand re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere.

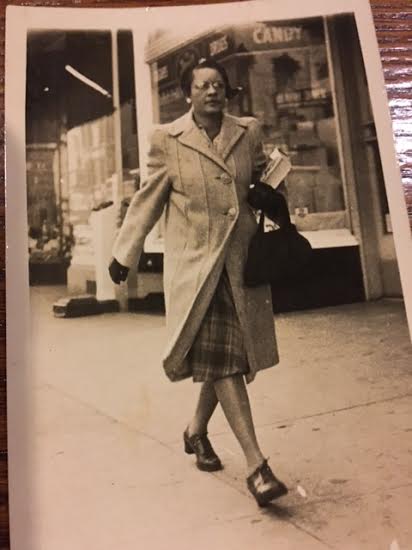

She wasn’t alone. Hirasaki was one of several hundred women working for NASA behind the scenes in Houston. You might not know if you scanned the black-and-white news photos of the time, which often featured scores of white men with pocket protectors seated inside NASA’s famous Mission Control. But that doesn’t mean they weren’t there, something that former First Lady Lady Bird Johnson noticed.

“I’m very proud of the role women are playing in space,” Johnson noted in a diary entry reflecting on the Apollo program. “About 20% of the payroll at this spaceflight center consist of women. Ranging all the way from clerks and typists to aerospace engineer.”

One of those engineers actually worked her way to Houston’s Mission Control Center. Meet Poppy Northcutt.

“I did grow up in Texas. I went to high school in Dayton. Texas in Liberty County, and then I went to the University of Texas. I studied mathematics and when I got out of school i ended up working at TRW Systems which was a contractor for NASA.”

Northcutt landed in Houston in 1965 with the curious job title of “computress” – basically a gendered technical aide position. She was quickly promoted to work on Apollo 8 as a “return-to-Earth” specialist. She would become the first woman to work in Mission Control in a technical role. But like all women living in that era, her technical chops didn’t insulate her from rampant sexism.

“For many women, it was like for gravity is for you and I,” Northcutt says. “You don’t notice gravity until you go into a gravity free environment, or a heavy gravity environment.”

But that sexism didn’t necessarily always come from Northcutt’s male colleagues, she says. Once they saw that Northcutt was qualified and serious about her job, most of them came to respect her.

The media at the time was a different story. Northcutt says her age and looks received a lot of attention, and even sexual harassment from the press.

“I was doing an interview outside sitting somewhere,” she says. “And there was a photographer there, but I was concentrating on the person I was talking to. Then I glanced out of the corner of my eye and was like, “what?’ and his photographer is laying on the ground shooting up my skirt. So it was definitely a very sexist environment”