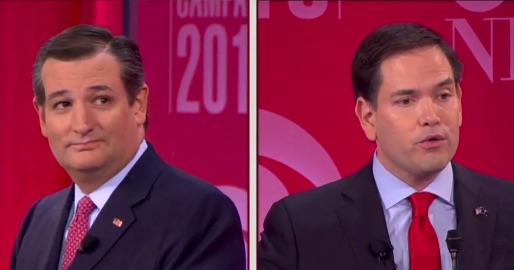

In the last republican presidential debate on Feb. 13, Texas Sen. Ted Cruz accused Florida Sen. Marco Rubio of having said something insufficiently conservative in an interview with the Spanish language network Univision.

Rubio bit back: “First of all I don’t know how he knows what I said on Univision, because he doesn’t speak Spanish.”

“Marco si quieres dicelo ahora mismo en Español, si quieres,” Cruz said back.

That’s telling, but not just because it says that candidates are clearly conscious of the Latino vote. It also tells us how the public embrace of the language has transformed from something to be shameful about to a symbol of sophistication and worldliness. Now there’s pride in speaking the language, where just a few years back it was something many everyday people tried to hide.

For Ida Maldonado, Spanish was the intimate language – the almost secret language her mother spoke with the children.

“I remember all of us sitting around while she read us all these stories. Well, she didn’t read them, she told them by memory,” Maldonado says. “I remember the Princess and the Frog the most and, of course, Cinderella and stuff like that.”

But that was only at home – at school it was very different.

“We couldn’t speak Spanish because we weren’t allowed,” Maldonado says. They told us in all the classes ‘You need to start speaking only English.'”

Now, Maldonado has forgotten most of her Spanish. “And, it’s kind of sad to me – you know?” she says.

Like Maldonado, Republican Presidential Candidate Ted Cruz speaks very little Spanish. But Laurel Stvan says that doesn’t matter. The exchange he had with Marco Rubio was strategic – more specifically it was what she calls strategic code-switching. Stvan is a linguistics expert at the University of Texas Arlington.

“As if to prove that he was a real Latino, right? And it wasn’t a super fluent performance but it didn’t need to be, because the switch out of English – that was the point,” Stvan says.

But what did it accomplish? Did it translate into “I can appeal to English speakers and Spanish speakers alike?” Did it translate into “I am worldly and well educated?”

Mark Hugo Lopez says maybe. Lopez is with the Pew Research Center. He says political intentions may not always be clear – but what is clear are the numbers.

“Spanish is the second most spoken language in the United States – by far,” Lopez says. “I mean the number of people who speak Chinese, the third most spoken language, is far behind the 40 million who speak Spanish.”

Something else that’s clear is who speaks Spanish.

It used to be, generally speaking, only Latinos. But times have changed.

At the Magellan International School in Austin, Principal Marisa Leon is surprised by the success of her Spanish Immersion program.

“We opened only with 45 students which was a big number for a start-up school and now we are at 450 – almost,” Leon says. “Almost 10 fold in six years.”

The majority of the families in the program – 75 percent – are not Latinos and the parents don’t speak Spanish at home. Such is the case of Ana Alleman.

Alleman tells me she’s going to read a poem she wrote called “What the wind whispers.”

Principal Leon is beaming while she listens to Alleman’s poem. After all, the expected outcome in an immersion program is fluency.

Leon says she gets a sense from parents that, just as politicians are strategic in their adoption of Spanish, parents are too.

“Parents are saying ‘Wait, it’s not enough to only speak English and speak one language. If we want our children to be successful and be competitive and actually be citizens of the world, they need to speak at least one more.'”

Right now that language, the one that makes sense to learn, is the same one that – years ago – Ida Maldonado was stripped from.