“Welcome to Amarillo. Home of 160,000 nice people and a few soreheads,” reads a chipped and faded sign planted beside an Amarillo road.

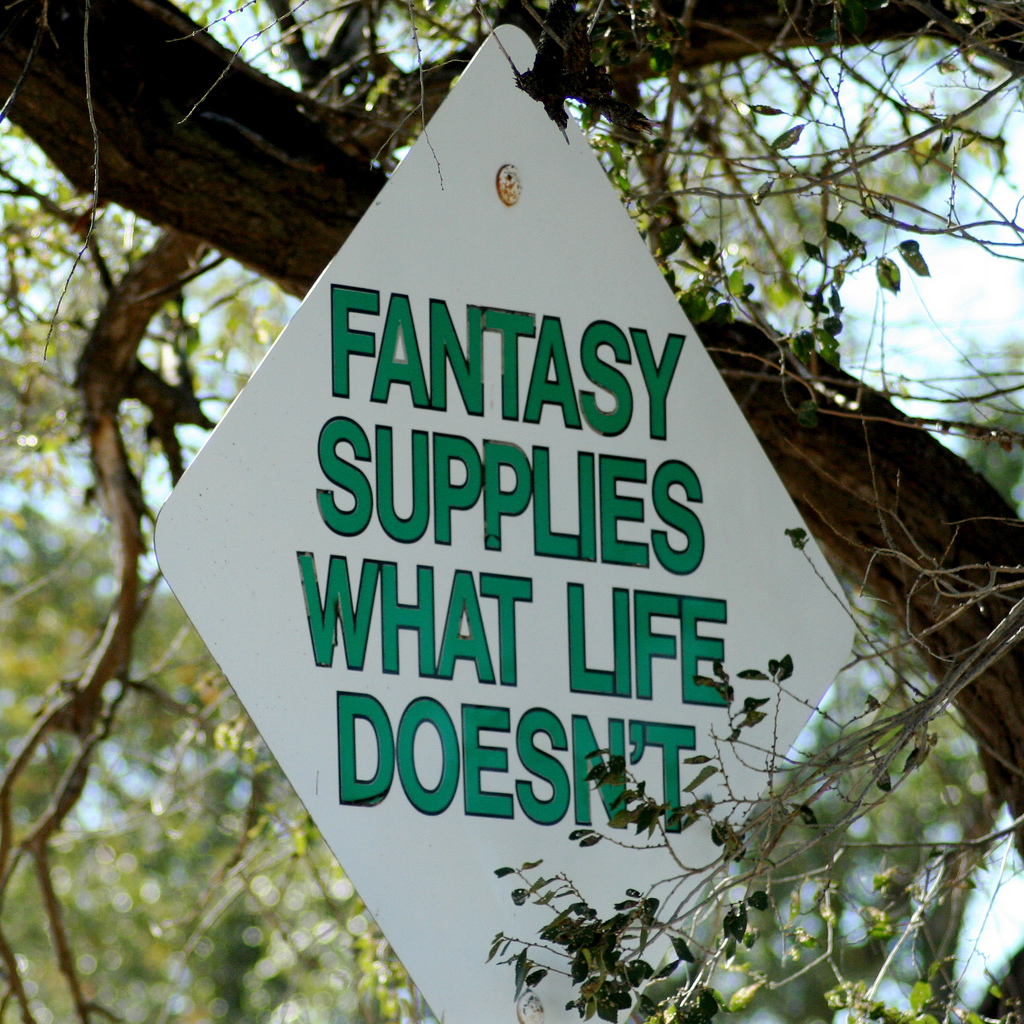

This is just one of thousands of fake street signs posted by oil magnate Stanley Marsh 3 across the city. The diamond-shaped signs, six to eight feet tall, feature paintings, variations on common phrases or passages from literature. Marsh, also a supporter of public art, was best known for the famous Cadillac Ranch installation.

Now a group called “Erase the Marsh Madness” wants the signs taken down, because of charges Marsh faced for sexual assault. Although those charges were dropped after Marsh died last year, the group claims the fake street signs are a painful reminder for alleged victims.

Aaron Davis, public safety reporter with the Amarillo Globe-News, talks to the Standard about the situation surrounding Marsh’s memory.

“It was alleged that he had been sexually abusing many young boys and one lawsuit was settled in 2013 with 10 boys alleging sexual misconduct with Stanley Marsh 3,” he says. “A recent lawsuit was filed with eight plaintiffs against the survivors of Stanley Marsh 3’s estate.”

Davis spoke with the alleged victims in the most recent lawsuit. “They said that every time they go out to get some milk at the store or go out to their jobs, they have to drive past these signs that, to them, were written in Stanley Marsh’s voice and triggered bad memories,” Davis says.

Many of the signs, however, are on private property, not on public roadways.

“All of the people who have these signs initially opted in for them in the 90’s when they were installing the signs,” Davis says.

Davis says that according to art professors and former members of the Dynamite Museum group – the artistic collective who put up the signs – the signs have an artistic value “as being in the historical vein of public art.”

Listen to the full interview in the audio player above.