Popular culture often has a reputation for being a less serious form of cultural expression. Even if that’s true, others may argue that doesn’t make it any less valuable. Indeed, one historian suggests pop culture was one important the avenue through which Latinos and Chicanos/Chicanas have made their mark in American society.

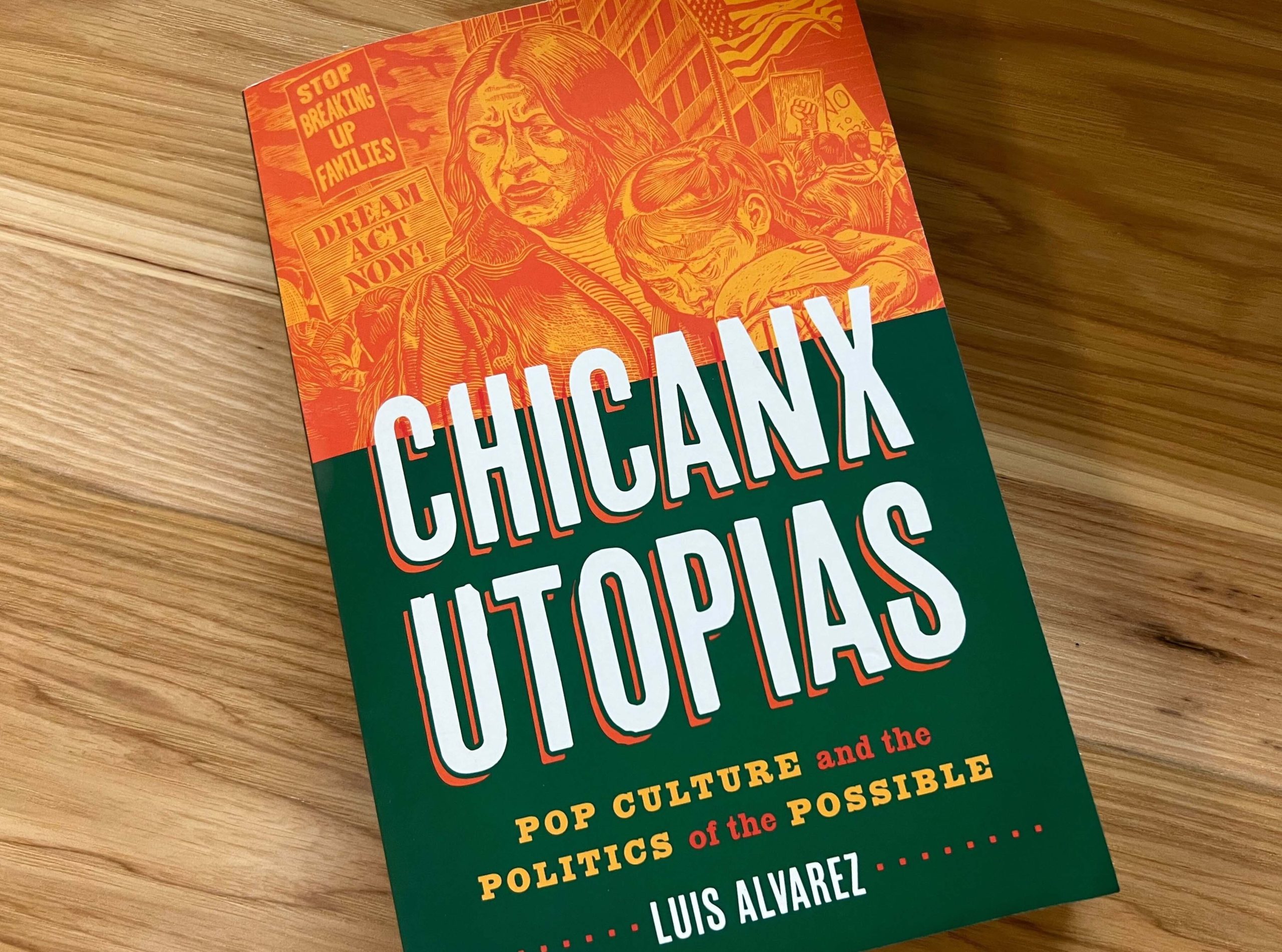

These sometimes brief moments of Chicanx visibility in television, music and film were hopeful signs that America could be more equal, more inclusive, even if they didn’t last long. University of California, San Diego history professor Luis Alvarez explores these moments in his book “Chicanx Utopias: Pop Culture and the Politics of the Possible,” and argues they were a step in the right direction not only for Chicanx people living in the United States, but for other marginalized groups too. Listen to the interview with Alvarez in the audio player above or read the transcript below.

This interview has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: Let’s start off with this general idea of cultural utopias: what does that mean to you?

Luis Alvarez: Great question. Utopias – it’s in the title, after all – is really about the visions and impulses of utopia that weren’t just part and parcel of Chicanx pop culture, but really part of people’s everyday activity. When I say “utopia,” I don’t mean just blueprints of finished communities or finished, completed projects, but really those small, profound moments where people might even for just a second enact or articulate the visions or impulses of a better world. These are moments of utopia that are really always in process, always unfinished.

And this is really not a book about utopia as all world-changing and Revolution with a capital R, but really more about the kind of many, everyday moments that gesture to the possibility of a different world that might function more like a kind of series of revolutions, with a small r. This is really what I mean by the kind of politics of the possible that’s in the subtitle of the book. And sometimes these pop-cultural politics went on to spark bigger changes, and sometimes they didn’t. Sometimes they were co-opted by mass culture, and sometimes they weren’t.

That reminds me of a recent conversation we had on our program about the young people in San Anrtonio who had developed their own style of rock ‘n’ roll because they felt excluded from the rock scene that had emerged nationwide in the late 1950s and early ’60s. They called it the “West Side Sound.” They didn’t even realize what they had created at the time, but they were building on the idea of inclusion. Would you describe that as a Chicanx utopia?

Absolutely. And I think the West Side Sound in San Antonio mirrored different sounds and soundscapes across the country, including the one that I write about in Chapter 2 of the book, which is really the Brown Eyed Soul scene in East Los Angeles that was unfolding around the same time and not-too-distant place from what was happening in San Antonio.

This is very much a book about what happens in these cultural worlds, not only making the argument that they matter, but sometimes [that] what happens in these cultural worlds – whether it’s music or visual art or film or even television, which I write about in the different chapters of the book – what happens in these cultural spaces sometimes doesn’t happen in other arenas of life, whether it’s electoral politics or labor organizing or what have you.

In your chapter “Chico and the Man,” which was a comedy series on NBC back in the 1970s, you write about how that was a sort of double- edged sword. Can you explain why?

“Chico and the Man,” along with “Welcome Back, Kotter,” the old sitcoms from the mid-’70s, are part of Chapter 3. And really what I want to convey in that chapter is that sometimes utopias were co-opted by mass-culture industry – in this case, the television industry.

“Chico and the Man” was a remarkable show, in part because it featured one of the only Latinx characters on television at the time. Freddie Prinze was a Puerto Rican; actually, he referred to himself as a “Hunga-rican.” And he started as a young Chicano male in this show set in East Los Angeles. And that created controversy, right? There were a lot of Chicano activists at the tail-end of the Chicano movement that were upset that a Chicano wasn’t portraying a Chicano on TV.

And there were all sorts of conversations about how the possibilities of what it meant to have a main character on TV that connected to the Chicanx and Chicano/Chicana communities at a really important time in American history – a time when we were really trying to make sense of what race relations in the country would look like after the end of the civil rights movement, and what that really meant for Chicanx communities. And to see that they didn’t really have the representation, they didn’t have the voice in the scripts and in how the storyline played out on television, really spoke to the limits of what could be portrayed, or what might be portrayed, in this particular cultural medium of television.

What I really argue in that chapter, both in terms of “Chico and the Man” and “Welcome Back, Kotter,” is that a kind of idea of multiracial harmony on these sitcoms was really shown to be available only to a few folks, and Chicanx people and communities weren’t always included in those conversations. And that’s one of the real limits of cultural utopias is that sometimes they don’t work out for the folks who are most invested in them.

What were you hoping people would take away from the book, as you were writing it?

I’m really writing this book for all folks. I think that if there is a takeaway message it’s that Chicanx pop culture is full of beautiful stories and dreams of a better world, that those sorts of things aren’t the property of Chicanx folks. But I focus in on their dreams and stories; I see it in the 1954 film “Salt of the Earth,” which is the first chapter of [my] book, and I think it weaves its way through the other chapters of the book.

I want us to really look at and listen to our TV, film and music with an eye for the political possibilities, the moments when people came together across racial lines to challenge segregation, which is a huge part of the book. Connections to the past – to really imagine a different future.

So I think if we listen and watch the artists and the singers, the actors, the producers that are in this book, they have the the capacity to teach us something about the power of culture to change the world, not just how Chicanx folks have long fought against forces that are more powerful than themselves, but really, how these utopian visions and impulses that might have been obscured in history can spring from just about any place or time from the everyday activity of folks.

One other follow-up point is that a big part of this book is about people who aren’t of Mexican descent, and who engage, produce, create, circulate, consume what has been considered to be “Chicano.” Popular culture that happens in film, that happens in music, that happens in the poster art, there are African Americans, Japanese and Japanese Americans, Jewish folks and all sorts of others that are engaged in the creation and the production, the circulation of Chicano popular culture that really make it a multiracial story. And that’s one of the arguments that I really want folks to take away, that being Chicanx or Chicano/Chicana, I want us to think about stretching the kind of ethnoracial logic of what that means, and the kind of territorial logic, that geographic logic, of what that means. And that really means writing for a bigger and broader audience.