It’s hard to miss the large colosseum-like structure off Ranch Road 1017 in the Rio Grande Valley. It’s the Santa Maria Bullring and it’s where Fred and Lisa Renk have been running bloodless bullfights for the past 19 years.

“Bullfighting in Mexico – it’s called the ‘ballet of death.’ And in the United States we call it ‘the ballet of life.’ Because the bulls live, we don’t injure them at all and they go on to the PBR and chase clowns the rest of their life. I probably got 300-400 out there on the rodeo circuit right now,” Fred Renk says.

82-year-old Fred greeted me at the front La Querencia Ranch where he lives and runs the Santa Maria Bullring.

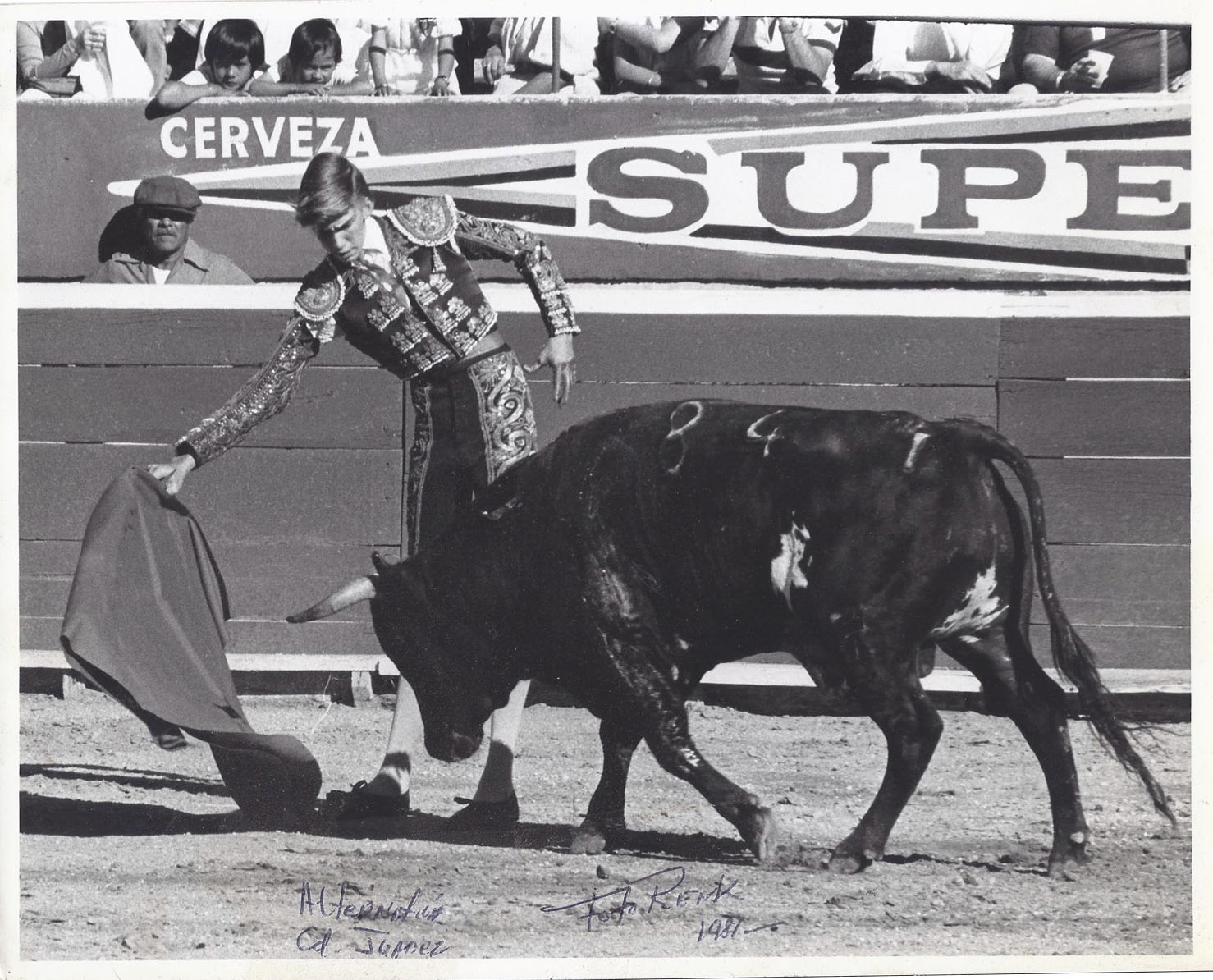

We walked under a pavilion through a museum of sorts. Almost every vertical surface was covered with pictures, clippings and memorabilia of bullfighters – matadors from all over the world – chronicling a tradition that is centuries old. But here at Santa Maria, these bullfights break tradition.

“It ends with the removal of a flower – a symbolic kill. You’ve got to go in over the horns, just like you would with a sword, and you grab that flower,” he says.

But Fred’s wife Lisa says it’s not as mild as it sounds.

“It’s more dangerous because of the fact that we don’t shed the blood of the animal or kill the animal, which makes for a more dangerous animal,” Lisa says.

“It is really dangerous to fight a bull that way,” Fred says. “But we’ve been doing it. In 1986, I put on bullfights in the Astrodome, Madison Square Garden. I’ve been all over putting on bloodless bullfights all my life,” Fred says.

Fred first became fascinated by bullfighting in 1952. He was an exchange student in Chihuahua, Mexico, studying to be a priest. He and a fellow seminarian decided to see a fight at the nearby bullring.

“I didn’t know anything about it. But I was sitting next to an old man and he started explaining it and I never forgot it,” Fred says.

He left the seminary, joined the military and in the years to come, wound up a salesman along the border. But something was missing. He just couldn’t shake his fascination with the matadors he saw. So eventually, he decided to study bullfighting. But by that time he was 28 years old – late to the game for a aspirante, or matador in training.

“After I got in and got hurt two or three times, you know – they say you should give up, but you don’t. Not if you really have the fever, the worm, they call it,” he says.

The life of a novice bullfighter, or novillero, is not glamorous. Most retire relatively young, with little money to show for the hours of training and dedication. And most never make it to the rank of matador de toros.

“Well, there’s not very many matadors in the world. There’s a lot that try and very damn few make it,” Fred says.