Willie Nelson’s landmark album “Phases and Stages” was recorded in 1973. It was unlike anything being done in Nashville – a concept album, about a relationship coming apart. Metaphorically speaking, Willie Nelson was separating from Nashville too, a place where he’d long written songs for others. But where the Nashville machine kept him from doing what he loved to do, his return to Texas was a symbolic break with the conservative conventions of the country music industry.

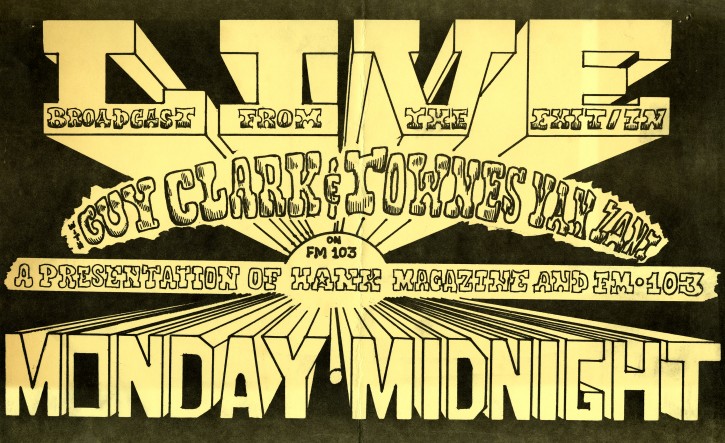

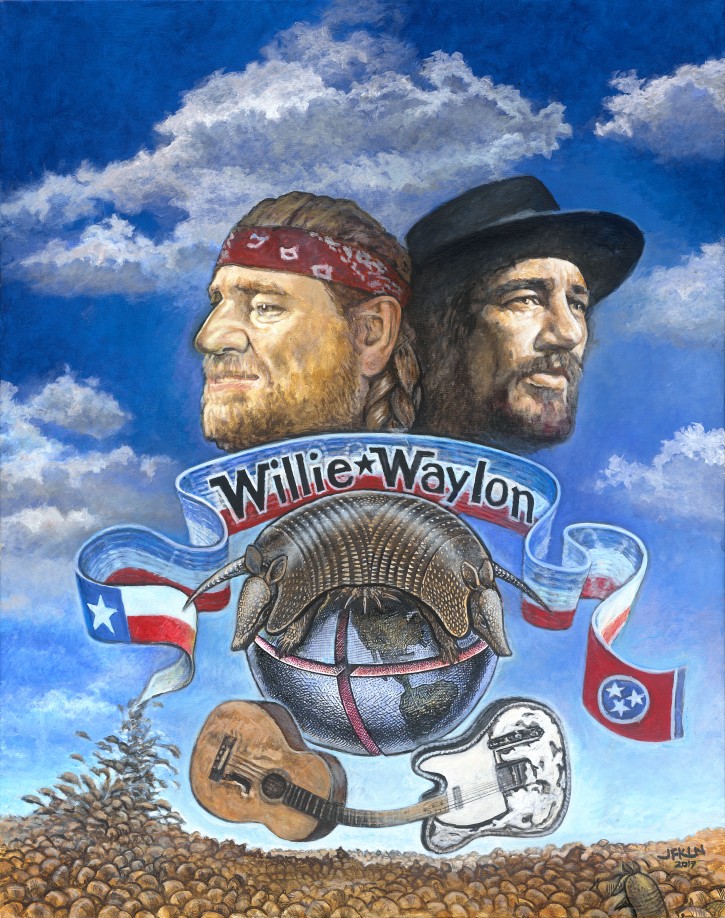

It is now part of Texas lore that Willie kickstarted an outlaw movement, that would include Waylon Jennings, Jerry Jeff Walker, Guy Clark, Steve Earle, Billy Joe Shaver and countless others who brought country back to its rebellious roots.

Friday, the Country Music Hall Of Fame in Nashville opens a new exhibit focusing on the story and influence of that movement. Peter Cooper is a country music journalist, senior lecturer at Vanderbilt University’s Blair School of Music and co-curator of “Outlaws & Armadillos: Country’s Roaring ’70s,” He says the exhibit celebrates more than just the music the 1970s outlaws made. There’s the door of the Luckenbach General Store that Hondo Crouch converted from a post office into a bar and dance hall.

“Jerry Jeff Walker looked to Hondo Crouch as kind of a father figure and creative north star,” Cooper says. “Jerry Jeff decided to make an album there in Luckenbach.”

The album, named for a bumper sticker on the general store’s door, was “Viva Terlingua.”

The exhibit also features the actual broken spoke that gave the legendary Austin music venue its name.

“Maybe when people hear about an exhibit called ‘Outlaws & Armadillos’” they’re gonna think that this is… Waylon and Willie and the boys,” Cooper says. “It certainly has Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson items, but it’s much deeper than that, and it includes people that were absolutely integral to the history of Texas music, and the development of songwriting.”