This story originally appeared on KERA Breakthroughs.

Warren J Smith III didn’t want to lose his leg, but an infection just kept coming back.

It all started with a motorcycle accident in 2009. Since then, he’d had dozens of operations and round after round of antibiotics. He’d spent countless days in a hospital bed, isolated in sterile rooms where doctors and nurses had to put on plastic gowns and gloves.

“It was like the kid in the plastic bubble,” he remembers, laughing.

At 49, out of his job in sales, Smith ended up at Parkland Hospital. If he wanted to keep his left leg, he’d need to complete another course of antibiotics – intravenously – through a port in his arm. For patients with health insurance, this usually means a minor surgery, then daily visits from a home health nurse to give the medicine. For uninsured folks like Smith, it means being stuck in the hospital for weeks, sometimes a month or more, or going to a place like a nursing home. An experimental program at Parkland went in a new direction, sending patients like Smith home with the tools to care for themselves.

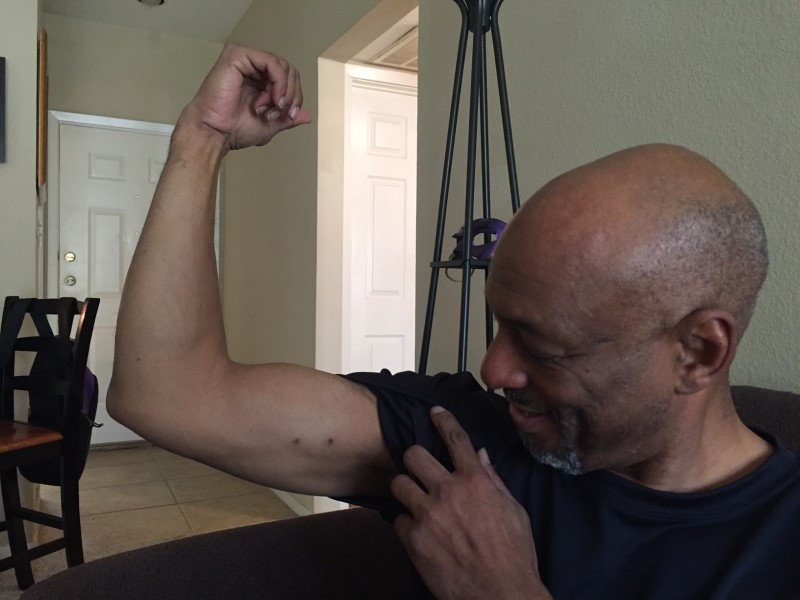

For a month, every day around seven o’clock, Smith would open his fridge, grab a plastic bag with antibiotics, then clean and connect it to a small plastic tube coming out of a vein in his arm, right below his bicep. To get the medicine to drip in, he rigged together an IV pole with a metal hanger.

Smith would take the hanger and, depending on where he wanted to be in his apartment, hang it on a lamp, or a picture frame above his desk, even on a cabinet above the stove so he could cook. He didn’t have to be in the hospital, taking up a bed that could be used by a sicker patient, and, he felt free.

“Having the IVs and administering at home gave me that self confidence that I’m still somewhat in control,” Smith says.

What’s incredible isn’t that he did this – without any infections or bleeding or allergic reactions. It’s that other uninsured Parkland hospital patients were doing it as well…Nearly a thousand of them.

Dr. Kavitha Bhavan, who led the research at UT Southwestern and Parkland, says the 944 uninsured patients who administered their own IV antibiotics were wildly successful. She points out there was a safety net built in – weekly checkups and a 24-hour hotline. Still, the results of the four-year study — just published in PLOS Medicine — challenge traditional ideas about what patients are capable of.

“Not only do they do it well, but they’ve done it better, in our study, when we looked at the controls who went home with some home health services,” Bhavan, who is also Medical Director of the Infectious Diseases Parenteral Antibiotic Therapy Clinic at Parkland, says.

“Most physicians will tell you we didn’t think that could be done,” Bhavan says. “[Succeeding] may be something as fundamental as tapping into engaging them in their own care.”

It’s not that patients have never been shown how to give themselves antibiotics through an IV – Dr. Donald Poretz, an infectious disease physician in Fairfax Virginia, says some well-educated, insured patients have been taking medication like this home for decades, this patient population though, was different. Many were far below the poverty line and with very little education.

“So this is unique,” Poretz says. “It proved it was just as efficacious whether you had insurance, didn’t have insurance, spoke English, or didn’t, if you were adequately taught, you could do it.”

To teach patients, a group of nurses, doctors, and social care workers distilled the education to a fourth grade literacy level; they did bedside training with a photo-packed manual, and used technology. They put a QR code on every bag of antibiotics that links to a YouTube video in English and Spanish for easy access.

By letting patients go home and care for themselves, Parkland estimates in 2015 alone, the program helped it save more than seven million dollars — it also freed up 6,000 hospital bed days – for patients who have emergencies like heart attacks.

Warren Smith III successfully completed his treatment. But an infection came back, and surgeons had to amputate his left leg. Still, he finds solace in the fact that he tried everything he could, and in the process, he learned about his own body, and became empowered to care for himself.

“I try to tell other people you have to be willing to try,” Smith says. “If you’re just going to sit there’re and feel sorry, it’s not going to get better. And for me, that was the attitude I took.”

Smith and Dr. Bhavan agree – it’s possible for more uninsured people to get better, faster, at home, — so long as doctors collaborate, instead of treat patients.