This is the first story in TPR’s three-part series “Justice Ignored: Texas has a long way to go in helping child victims of sex crimes.” Read the second story here and the third story here.

On the last night Shawna Rogers could speak, she was lying.

The lie: that her friend from a treatment center, identified only as D.D. in court documents, had just gotten out and was visiting family. The truth was that both 17-year-old girls were on the run from treatment providers, foster care, state and federal law enforcement, or some combination of it all.

With the lie, she convinced her maternal grandmother, Michelle McConnell, to drive her to a stretch of quickly darkening country road outside of Alvarado, Texas. It was there in the waning light of an autumn day that the running — which had punctuated so much of Shawna’s life over the past three years — would finally come to an end.

The lack of street lamps made it harder to see anything on that October evening in 2021. But finally, Shawna made out the figure of her friend, standing in a driveway on the opposite side of the road. She asked McConnell to slow down.

The desire to help a friend, or the need to commiserate with someone who had gone through similar traumas, brought Shawna to the road that night.

McConnell attempted to pull into the driveway alongside the girl, but D.D sprinted across the lane.

“That’s fine, I got it,” D.D. yelled, bolting for the car.

McConnell stopped her two-door Ford hatchback in the road.

Shawna was excited to see her friend. She hopped out of the passenger seat and slid it forward to allow D.D. to get into the back.

The lights from a car traveling the opposite direction caught Shawna in the darkness. Shadows from her small frame stretched and disappeared as she was quickly engulfed back into the rural night. The car’s high beams continued on.

Those bright headlights passed an S.U.V. not far behind Shawna’s car, which was still stopped in the road.

The glare blinded the driver, Jesse Esparza.

Without slowing, he slammed into the back of Shawna’s car.

“It was like that car fell out of the sky on us,” McConnell said.

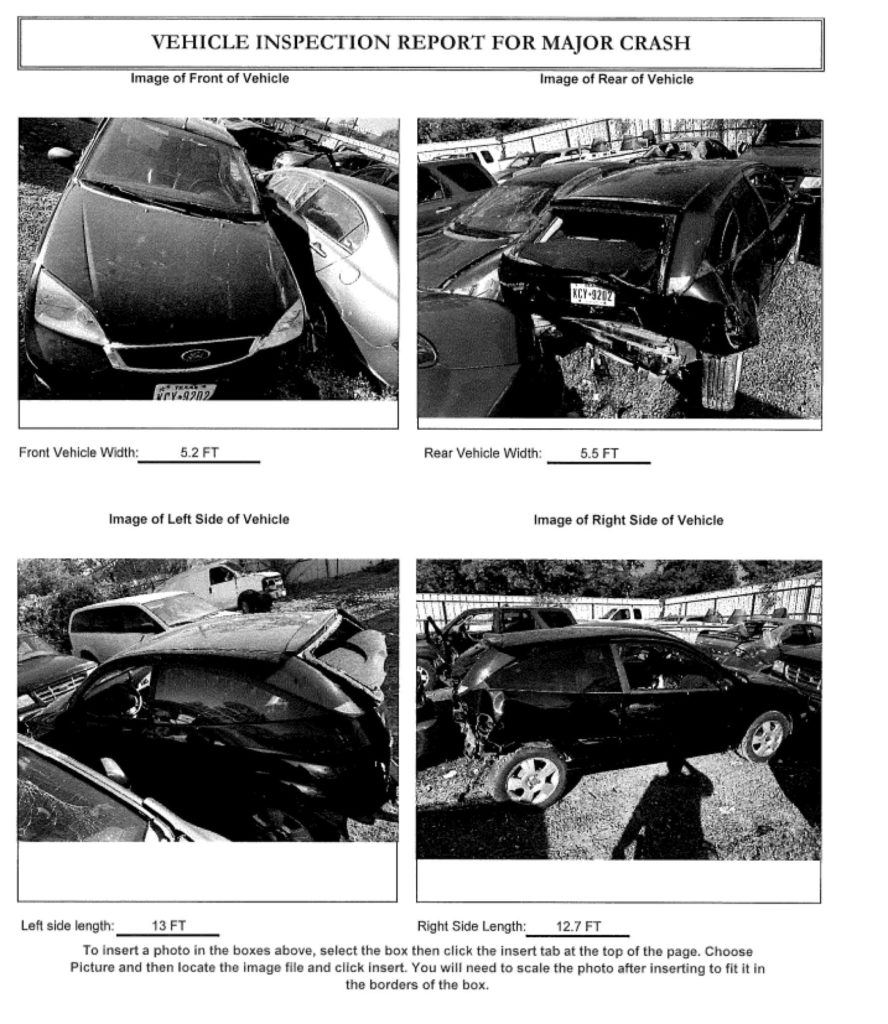

The Ford’s rear window exploded as the hatchback caved in. Most of the rear fender was gone — leaving an exposed rear tire.

The crash photos of the car Shawna was riding in.

Texas Department Of Transportation

The two vehicles rolled forward together, now quietly. They came to a stop on the side of the road. Shawna’s car limped into a small group of trees. That’s when Esparza heard the screaming.

“When I got out of my car the woman was screaming and yelling, ‘Where’s my (grand) daughter!’” Esparza told state troopers later.

Shawna had been bending to get back into the car when they were struck. Her body was thrown 40 feet into a ditch in a shower of broken glass, plastic and steel.

She was swallowed by the darkness. Disappeared. No one could see her.

Esparza called 911 and helped search.

McConnell was frantic. They couldn’t find Shawna.

“There is a lot of screaming and confusion at the scene,” read a note from the 911 operator.

Amber Deichert heard the collision from inside her nearby home. She ran outside to see what happened and found Shawna. She was alive, barely.

“Blood all over her face, ears, arms, stomach. She’s missing teeth,” Deichert told police “She wasn’t breathing at first.”

Deichert tried to clear Shawna’s airway, but there was too much of the dark viscous substance. She was choking. Deichert rolled her over to let the blood flow out.

A helicopter ambulance landed at a nearby elementary school and took Shawna to Texas Health Harris Methodist Hospital in Fort Worth.

The girl would spend her remaining days on a respirator without any brain function. Police guarded her room — driven to find the girl by people who called her “monster.” The road that led her to this hospital bed was filled with people indifferent to her needs and many who failed to see her as what she was — a child.

Robin Farris sits with the memorial poster she made for her granddaughter.

Paul Flahive / Texas Public Radio

The worst decision

Just two years before, Shawna led— on the surface — a fairly normal teenage life. Her grandmother worked long hours to provide for her. Shawna’s biggest concern at the time appeared to be ascending into high school just as her best friend moved halfway across the state.

But underneath that seemingly serene life lay the history of a troubled childhood and trauma.

Shawna’s parents both struggled for years with drugs and spent time in prison, said court documents. She was first removed from her mother’s home when she was 3 years old by Child Protective Services and given to her father.

Robin Farris, Shawna’s paternal grandmother, remembered when her son, Shawn Rogers, and a toddler showed up at her home in Marietta, Oklahoma, in 2008. Shawna’s father needed help with childcare, and Farris was the solution. She agreed to let them stay.

Farris was no stranger to struggle. She had watched Shawn (her son from her first marriage) fall into the trap of drugs. Her second husband had died, leaving another 12-year-old boy named TJ for her to raise alone. She also cared for her mother-in-law — a double-amputee who needed nearly constant help. She looked after both and worked two jobs, including one at a Walmart distribution center in a nearby town.

She faced a new challenge when her son arrived that day with Shawna, because he brought his addiction with him. Farris didn’t realize how bad the problem was until her own mother died. She left Shawn and Shawna at home and traveled to Illinois for the funeral. She returned a week later to a devastating realization.

“He robbed me blind,” Farris recalled. She said Shawn raided their garage. He stole her late husband’s tools, stored possessions and much more. “I mean, right down to my wedding rings — he pawned everything — and sold everything out from underneath me.” She added that he put about 1,000 miles on her car as he sold the items and found drugs to buy.

When Farris confronted Shawn about the incident, he packed up and fled with Shawna. “He took off with her because he was mad,” she recalled, “(but then) brought her back about a week later and said, ‘Here, you take her. All she does is cry for you anyway.’”

Shawna would later be haunted by the idea that her parents chose drugs over her. She talked about being “abandoned” by them. She would continue to seek her father’s approval and companionship.

“She loved her dad,” Farris explained. “She thought he was cool. He was fun. You know, he played with her, threw her up in the air and all that kind of stuff. But he was more of the good-time dad, not anything else.”

When Shawna was five years old, Farris used the money she inherited from her mother’s estate to file for legal guardianship of her granddaughter. She also struggled to keep her life together. She was still working two jobs, still caring for her mother in law, a stepson and still trying to be a mother to a little girl.

Laurie Monroe, Farris’ sister, wanted to help. She encouraged her to move to Austin. “My sister said ‘We can help you with Shawna. She can be raised with her cousin,’ ” Farris recalled. Laurie was raising her granddaughter as well. “I was, like, overwhelmed, so I said ‘ok.’ ”

Farris shared these memories with TPR in 2022, in her home. Down the hall was Shawna’s bedroom – a room her granddaughter never used. A few feet away from where Farris sat was a midnight blue urn filled with her granddaughter’s ashes.

The move to Austin was meant to make things better for herself and for Shawna. But Farris admitted that was the worst decision of her life.

“It just breaks my heart that I did this to this child. Because I feel like, if I hadn’t moved down there, then this would never have happened to her,” she said.

The dark road Shawna found herself on — the journey that would end with that ash-filled urn — began in Austin, she said, and with one man: Gerald “Jerry” Monroe.

‘Get things right within herself’

Shawna was described as a talented athlete who excelled in volleyball and basketball.

Courtesy Of Robin Farris

Shawna grew to be smart and athletic. She did well in school and was on both the middle school volleyball and basketball teams. Shawna even got a scholarship to join a basketball training program.

“She was really good at shooting. She was better at shooting than I was,” said Maggie Comstock, Shawna’s best friend. “But we would go to the courts right behind (Shawna’s) apartments, and we would always practice shooting.”

Maggie and Shawna first met at Anderson Mill Elementary School and were quickly joined at the hip.

“They used to call them the twins,” said Maggie’s mother, Jennie Pertzborn.

The girls spent hours at each other’s homes. Pertzborn remembered a girl who was unfailingly kind. She said Shawna always included Maggie’s younger brother Freddie in their activities, even though he was seven years younger. “He would go around at that age pretending to be a ninja, so she would run around and pretend to be a ninja with him,” she said.

Pertzborn said she brought a childlike innocence to daily life, despite being much older. Shawna grew so close to the family she took to calling Pertzborn “mom.”

Maggie often spent time at Shawna’s home in an apartment near the middle school. She had also eaten dinner with her a few times at Shawna’s great aunt and uncles — the Monroe’s home. Shawna called them “Ganga and Papa.”

When Farris moved with Shawna to Austin, they lived with the Monroes in their spacious home for a few months before finding their own place. The two continued to babysit Shawna for years after.

Gerald Monroe was a financial expert. He kept the books for a few organizations and was chief financial officer for Texas Foster Care & Adoption Services— a nonprofit that gets paid to place children in foster homes. He also started a nonprofit called Foster Kids & Families of Texas in 2011, according to state documents.

The family support and the fresh start in Austin might’ve promised a better life. But what seemed at first to be a second chance began to change.

Maggie did not feel comfortable when visiting the Monroe home, and she sensed Shawna did not want her to join her when she went to the house.

Maggie described Gerald Monroe as overly affectionate towards pre-teen Shawna.

“He would always give her money,” she said, noting that Shawna always had cash on her.

Shawna’s friends and family described him as showering the girl with expensive gifts throughout her childhood.

Farris grew uncomfortable with Monroe’s generosity. He had often found ways to give her money when the two first arrived. He had her do work for the foster placement agency, including processing payments from the state. Then he would try to give her cash. Once, he paid for an expensive car repair without her knowledge.

“And now I honestly think that he was grooming me too, in hindsight,” she said.

Finding her own place provided some distance from the Monroes, but it may have been too late for Shawna.

Shawna and Maggie finished middle school together, and they both had secured spots on Westwood High School’s volleyball team. But Maggie’s mother had remarried, and the family was relocating to Odessa. Shawna would have to attend the new high school without her.

Shawna did not like the “bougie” school, as one of her friends in treatment later referred to it.

Round Rock Independent School District had a higher income level. Farris earned about half the county median income. She lived with Shawna in an apartment across the street from the high school in an area where most owned their own homes. Farris cleaned the Monroe home to supplement her income at a grocery store. Shawna told people she didn’t feel she fit in.

Despite her problems with the school, Shawna did well in her first year, Farris said. But she also had new friends — boys that Farris instinctively did not like. One friend described the boys as “burnouts.” Farris also said this was the time when Shawna started using marijuana and Xanax, an anti-anxiety drug.

She would show up at home stoned or at times drunk with boyfriends. Once, she was so intoxicated that she fell into the street outside their apartment.

It was clear that things weren’t right. Shawna still saw Maggie every month or so, when she came to visit her father in Austin. And Shawna would make the six-hour journey to West Texas to stay with Maggie’s family.

“There was an uptick of drug use,” Pertzborn said. At first, she thought it was teenage experimentation. But it was escalating, and Shawna’s attitude and temperament had changed. She was quieter, and the last time she visited the family she wouldn’t come out of her room.

That last trip also ended in sadness. The two girls had a falling out. Maggie realized $100 disappeared from her nightstand, and Shawna was her only suspect. Shawna denied stealing the money.

Maggie’s mother stepped in. She sat Shawna down. “I didn’t tell her she couldn’t come back,” Pertzborn said. “I just told her she needed to get things right within herself before she came back.”

She hoped the new boundary would help Shawna. But the boundary became a chasm Shawna would never traverse. It would be the last time Shawna would spend time in the home with the woman she called “mom.”

Shawna and Maggie spoke only sporadically after that. Maggie remembered that the last time she saw Shawna was in the hospital after the roadside accident. Her “twin” was gone.

‘She wouldn’t have nobody’

As Shawna began her sophomore year of high school her behavior worsened.

Farris remembered how she would dress for school and the two would leave together to start their days. But then Farris would get a call at work saying Shawna hadn’t shown up for classes across the street.

Shawna’s drug use also increased, and it didn’t stop there.

“She was running away all the time, and disappearing on me for days on end,” Farris said.

Shawna’s abuse of Xanax grew to the point that if she overdosed or when she stopped using it, she would go into seizures. They ended up in the emergency room more than once.

Farris said she tried to take control of Shawna’s decline. But a tougher approach rarely yielded results — Shawna would just take off. She said she called the police 10-12 times to report her missing.

She learned her brother-in-law Jerry Monroe was still giving Shawna money. She asked her sister to make him stop. He didn’t, and when Farris found out why, she would never look at him or Shawna the same way again.

In March 2020, Shawna was 16. Farris took her granddaughter to get a late lunch. She wanted to understand what was going on with Shawna. She wanted answers. Farris begged Shawna to explain.

Shawna was anxious. She grew visibly upset from the conversation. Finally, she asked Farris to pull over. Farris pulled into the parking lot of a fast-food restaurant.

“She said, ‘Just get out of the car for a minute.’”

Farris got out and watched as the girl boiled over with anger. “She’s beating on the dash, kicking and screaming.”

Farris watched for several minutes and started to cry.

When she got back in the car, Shawna told her.

“Uncle Jerry” had molested her since the two moved to Austin, when she was 8 years-old, and the girl said it had escalated to rape.

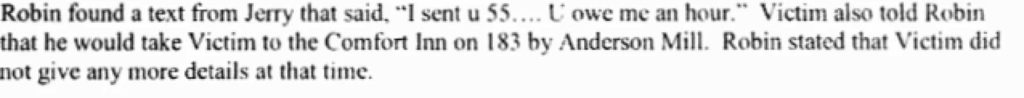

Shawna said in the last year Monroe would rent a room at a nearby hotel. He instructed her to use an Uber gift card he gave her to travel there. In the room he gave her money and forced himself on her, according to police documents. Shawna said it happened 20 times.

“She stated that it happened every time she went,” said a police affidavit. “He then gives her money after so she will not say anything. …”

A portion of the probable cause affidavit for Gerald Monroe.

Austin Police Department

Farris was dumbfounded. She asked why she had never told her.

Shawna explained that Monroe warned her that if she did, Farris wouldn’t love her anymore. ”That I’d go up and leave her. She wouldn’t have nobody,” Farris said.

The girl who was haunted by the absence of her parents was made to think she would have to choose: keep the one person in her family she still had or tell the truth.

Farris’ world cracked open, her memory actively reorganizing itself. The running away, the drug use, the teenage rebellion — she now understood it as coping. The elaborate gifts and spending from Monroe — once the attention and love of a wealthy relative — she now saw as hush money.

“It was devastating. I was mad. I could not believe he would do this to a child,” she said.

Her heart was pounding as she tried to calm down. The grandmother sat in the car and sobbed with her granddaughter.

When they returned home, Farris looked up counselors. She called crisis lines. She said she called Child Protective Services and the police.

But the situation didn’t improve. When Farris called the police, Shawna refused to speak with them and would run away. When Farris set up counseling sessions for her, Shawna attended one and never went back.

Farris said she found an old text message from Monroe on Shawna’s phone saying, “I sent 55…U owe me an hour.”

Two weeks later, Shawna overdosed on Xanax at a nearby park. Convulsing from a seizure, she was brought to the emergency room. According to a police affidavit, this was the first time law enforcement officers spoke to Shawna.

CPS launched an investigation into Jerry Monroe for sexual abuse.

But when a CPS investigator told Monroe to stop contacting Shawna, a police affidavit said he tracked her down at a friend’s house. It said that Monroe “came to talk to her after CPS came to talk to him … and confronted her and told her that she was lying.”

Shawna, in a panic, denied she told anyone and called her grandmother. “‘Nana, he’s here,’ ” Farris said Shawna told her. She could hear the fear in her voice. “He was asking her, ‘What the hell was going on?’ I said, ‘Go back in the house. Shut the door, lock it. Don’t talk to him.’ ”

And then Laurie Monroe, his wife and Farris’ sister, called. She said Shawna was a liar and an addict. Farris recounted that she complained about what the allegations would do to her husband and their lives. His work at the foster placement agency would be jeopardized.

“‘Look what I’m gonna lose,’” Farris remembered her saying. “‘I’m gonna lose my house, my car, everything.’” Farris responded: “Well, what has Shawna lost? She’s lost her trust, her innocence, somebody that was supposed to watch out for her, not abuse her.”

The sisters have not spoken since.

In a phone interview with TPR, Gerald Monroe denied that any of this happened. He said Shawna was good at lying and misrepresented their relationship.

“She was psycho dialing me. I don’t really want to talk about it. It’s over. There was no sexual assault. I didn’t pay for sex,” Monroe said.

Shawna was a bad kid running with a bad crowd, he said. He only got her hotel rooms because she was running away, and she needed a place to stay.

“I gave her money, and I gave her a room because she had no place to go,” he said.

He blamed Farris for Shawna’s problems and claimed that she physically abused her granddaughter. None of Shawna’s friends, family, or treatment providers TPR spoke with confirmed the allegation.

Child Protective Services found “reason to believe” that Shawna had been sexually abused by her great uncle from the time she was 8 years old in June 2020, according to a federal court monitors report.

CPS found no evidence of abuse from Farris.

An investigator from Austin police’s crimes against children unit attempted to speak with Monroe but he declined. It isn’t clear what happened next in the investigation, but Monroe wouldn’t be arrested until the week of Christmas, eight months after the complaint.

The delay was unusual in cases like this, according to experts TPR consulted, and could have cost investigators access to digital evidence.

A federal court report referencing Shawna said her abuser had video recorded at least one incident using his phone. It is unclear if that was ever recovered by police.

Investigators did not respond to TPR’s requests for comment.

Farris said she didn’t understand why he wasn’t immediately arrested. She said Shawna was scared. “She just didn’t know what Jerry was liable to do. She was scared. … She doesn’t want to be at home alone. She was truly running scared,” Farris added.

Throughout those eight months, Shawna’s life continued to fall apart.

‘Why is no one helping?’

As Shawna worsened, Farris had a recurring thought: “I was thinking that they’re going to find my child dead somewhere,” she said, “And I’d have to go and identify her.”

After work one day in May 2020, Farris returned home and found a note taped to the refrigerator. It was from Shawna. It was a suicide note.

In it, Shawna blamed Farris for her sexual abuse because she allowed her to be at the Monroe home. At one point it read, “sad how your whole shitty rapist gets away with everything.”

Farris was terrified. She searched the house. She called the girl’s friends. She couldn’t find her. Her calls went to Shawna’s voicemail. She texted her but got nothing back. After a sleepless night punctuated with attempted calls Shawna finally answered. She told her grandmother she was fine and that the note was “nothing.”

Shawna later admitted she tried to overdose on drugs, but the friends she was with saved her.

Police probable cause affidavit excerpt.

Austin Police Department

Farris checked her in to Austin Oaks Pediatric Behavioral Health Hospital for the suicide attempt. But three days later, when the hospital felt Shawna was no longer in crisis, it released her.

Waco Center for Youth, Cedar Crest, Bluebonnet Trails: Farris reached out to at least a half dozen other facilities across Texas. What she found was wait lists and rejection.

“I’ve been through people like crazy trying to find any help I could for this child. And it’s just like, I was getting blown off so much. It was like, ‘Why is no one helping?’”

Texas ranks last per capita in the number of mental health personnel. These long waiting lists for pediatric mental health needs are no surprise to those who have dealt with them.

“I think that there is a shortage in general of therapeutic providers, especially who are adept at working with kids and kids that have been sexually abused,” said Judge Aurora Martinez Jones, a state district court judge in Travis County who deals with youth in foster care.

She said even for private, more well-off families, the waiting lists can be a challenge.

But the wait proved too long for Shawna Rogers, whose grasp on her old life had slipped away.

By late May, she was only occasionally staying with her grandmother. She would often sneak into their apartment while Farris was at work, shower, and leave again. She was partying more often. It was at a friend’s party where she met Jamil Watford, a 23-year-old man who had multiple run-ins with police.

Within days of meeting him, the girl was staying in his hotel room. She believed the two were dating. He posted photos of her semi-nude on social media advertising her for sex. Before long, she spent most of her time with him in hotel rooms where men paid to rape and sexually assault her.

Chris Churchwell allegedly paid to rape Shawna.

Wilson County

Middle-aged men like 38-year-old Christopher Churchwell paid Watford to rape the girl, according to state investigators.

The arrest affidavit includes pages of text messages arranging the first encounter with Shawna or someone posing as her. The arrest affidavit references several videos of Churchwell sexually assaulting and raping the girl.

Phones later recovered by police show multiple men paying to have sex with the child.

According to multiple people who spoke to TPR, Shawna was plied with methamphetamines and Xanax, then raped repeatedly.

Watford also used her photos to set up fake sexual encounters, luring men to rooms where Watford or his associates would rob them, according to court documents.

Farris was unaware Shawna was being trafficked. She only learned who Watford was when Round Rock police called her on July 5, 2020, and asked her to pick up her granddaughter.

Shawna was discovered in Watford’s bed at the Element Hotel.

“Shawna was in bed and appeared to be intoxicated and scantily clad,” a police officer wrote.

There was a laptop with a camera pointing at the bed, according to a source with knowledge of the investigation.

Watford was arrested for drug possession. Police had discovered 1.26 grams of alprazolam (about four Xanax pills) in the room. Despite evidence of sexual assault of a minor, the production of child pornography and trafficking, Watford wasn’t charged.

“You’ve got a partially clothed 26-year-old (sic) and a partially clothed 16-year-old with cameras set up facing a bed, and it’s just a shrug of the shoulders,” said a source with knowledge of the case.

Neither Watford nor his associates would ever be charged with any crimes committed against Shawna Rogers. And she wasn’t the only victim, said a source with knowledge of the case; Watford and Perkins trafficked at least one other girl.

Shawna was advertised for sex on social media by traffickers and potentially later by herself.

Farris packed up Shawna and her car with as many possessions as she could and drove them 250 miles north to Gainesville, Texas, on the state’s border with Oklahoma. She planned to have the two stay temporarily with her stepson TJ. They were not going to live in Austin anymore.

Farris thought leaving Austin was the first step toward Shawna’s safety, stabilization and eventual recovery. She had survived emotional abuse, sexual abuse, suicide, drug abuse, and rape. Farris thought Shawna had a chance to be done with her past. What she didn’t realize was that Shawna’s past wasn’t done with her.

‘She lit the fuse’

On July 31, 2020, two farmers in Manor, Texas, found the body of Christopher Branham.

Having spent a month outside in the Texas heat, the body was too desiccated and decomposed to readily identify. DNA and dental records would give a name to the body. But it was readily apparent that he was murdered. There were two bullet wounds to his head.

The 26-year-old had been missing since June 27. Branham had two children and an ex-wife. He worked in decorative concrete, and he labored long hours in the Texas sun.

Conny Branham, his mother, had checked her son into the Red Roof Inn on June 19. Chris had been staying with his parents — Conny and Jim. Conny said they had argued that day, and the two needed space.

His parents were very involved in the investigation into his disappearance. They canvassed the hotel. His sister called hospitals. They reviewed internet, text and phone call traffic to his phone — which they could review remotely. Jim drove around in his car, scouring the area.

Chris was an easy going and friendly man who loved sports. His parents think it was this friendliness that led to him meeting the men accused of murdering him.

“He would talk to anybody,” Conny Branham said.

A few days after he checked into the Red Roof Inn, police documents showed Chris was hanging out with Jesse Perkins, Kyle Cleveland and Anthony Davis. His mother said she is sure Chris did not know the men.

Regardless, the four men traveled to a La Quinta hotel in neighboring Travis County where Jamil Watford stayed with Shawna Rogers.

Police records and a source with knowledge of the case suggested Chris did know the men that killed him. The last call made with his phone number was to Jamil Watford.

By the time of the meeting, Shawna had a recently inked tattoo, a small, green money symbol between the thumb and index finger on her left hand. Watford had branded her with his symbol that day.

He believed that he owned her. Another minor child victim was identified in a neighboring county with the same tattoo, according to a source with knowledge of the case.

Police documents TPR reviewed didn’t give an idea as to why Chris spent time with men who were previously accused of drug dealing, sex trafficking, and robbery.

“Why was he in that room?” asked Robin Farris. “Was he there to do something he shouldn’t do to my granddaughter?”

None of the affidavits TPR reviewed answered the question of why he was there, nor said explicitly he had a connection with the group.

“He was there for purchase,” said Zaneta Castro, Shawna’s case manager at a treatment facility. Shawna told her that Branham was there for drugs.

“They weren’t selling Shawna to him. He was there for drugs and also payment of drugs that he didn’t pay for,” Castro said.

Kirsta Melton is a 20-year veteran prosecutor who used to run the Texas Attorney General’s human trafficking task force.

Jesse Perkins (upper left) Kyle Cleveland (upper right), Jamil Watford (lower left) and Anthony Davis (lower right). Cleveland and Davis pleaded guilty to murder.

“In my experience, the people who are most likely to be robbed by traffickers are either buyers, or people who are in some other way affiliated with a trafficker,” Melton said.

What is clear is that a bad situation got worse. The group accused Branham of being a “snitch,” or a criminal informant. According to police records, Watford knocked him to the ground, and the other men punched and kicked him. Shawna would later tell people that Watford told instructed her to record the assault on her phone, and she complied. Watford told Shawna to kick Chris. She kicked him four times.

Chris was unconscious. And Jamil and another man went through his pockets, removing cash and other items.

Men could be heard antagonizing Branham on the video calling him “snitch.” So could Shawna.

Branham’s parents were given access to the video, but said they never viewed it. “He never in a million years (would) have hurt (Shawna),” Conny said.

TPR has not reviewed the footage but descriptions provided of what the video shows diverge from the police’s account in terms of Shawna’s role.

The police affidavit described Shawna “stomping” on Chris’ head, and it attributed a broken jaw to the 5-foot-3-inch girl whose drug-addled body weighed a little over 100 pounds, rather than to the four adult men, each twice her size.

The description of the video in the affidavit said Chris appeared to be missing teeth and that “JUVENILE (Shawna) makes comment: ‘You look really fucking pathetic buddy.’”

The Branhams believe Chris would be alive today if Shawna hadn’t kicked him. “He was too damaged … so they made the decision to go kill him,” Jim Branham said.

A source with knowledge of the case said it was unlikely that the teenager broke Chris’ jaw. He was on his feet quickly and exited the room with Cleveland and Davis. The video later that night showed him back at his hotel walking without incident.

Shawna told Castro one of the men told her to leave after the video was made. She never saw Branham again. She later learned he was dead.

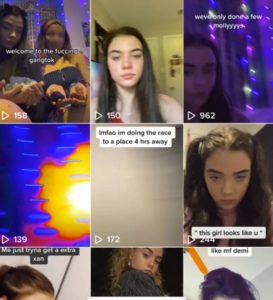

Cleveland and Davis took Chris back to his hotel room in Cleveland’s Toyota 4Runner, in the early hours of June 24, 2020. Video showed all three men entering and exiting Branham’s room multiple times. Then they left.

Davis later told police they took Chris to the hospital. Davis said he spent the next three hours digging a ditch for Cleveland’s employer and was paid $65.

Police timeline from arrest affidavit of Anthony Davis.

Court Records

Cleveland said that didn’t happen.

Police documents said Cleveland drove the men down a rural road, when Chris bailed out of the moving car. Davis pursued. He then shot Branham twice in the head with Cleveland’s gold-colored gun. Jesse Perkins told police that Cleveland and his girlfriend later threw the gun away.

At least one police document attributed confessional statements to Davis, including that he “sent him home” and that Chris was “in heaven.”

The police arrested Watford, Cleveland, Perkins, Davis, and Shawna. They charged Davis and Cleveland with murder. They initially charged Perkins, Watford, and Shawna with aggravated robbery. They later reduced Shawna’s charge to robbery.

The cases against the men have yet to be resolved, but the Branhams hold Shawna responsible for Chris’ death.

“She lit the fuse that killed my son,” said Jim Branham in an interview with TPR.

Did he see her as a victim of adult men? He responded: “Hell no.”

Ultimately Travis County prosecutors disagreed that Shawna was a responsible party in the murder of Chris Branham. She was sentenced to treatment for victims of sex trafficking at The Refuge for DMST (domestic minor sex trafficking) outside of Bastrop. She would be released on her 18th birthday with a sealed record.

“They treated her with total kid gloves. The whole justice system did. And it was just disgusting,” said Conny Branham.

During the Zoom hearing to determine sentencing, the Branhams railed against Shawna and the court for what they saw as a light sentence. They called the facility — which gave girls access to equine therapy by taking care of horses — a “spa” that they would like to visit on vacation.

Angry and powerless, the parents did not hold back.

“I have never been in a hearing where the court had so many admonishments,” said one person present, referring to the judge censoring the family.

They lashed out at Shawna calling her a “murderer” and a “monster’’ according to eyewitnesses. They threatened to sue Farris and Shawna’s father Shawn.

On the other side the Zoom hearing sat Shawna in Castro’s office at The Refuge.

“At one point she asked if she could hold my hand,” Castro recalled.

The hand was sweaty.

The minute the hearing ended and the screen went blank, Shawna started bawling.

“She just started saying ‘I am not a killer. I’m not a killer. I’m not a murderer,’” Castro said. “And she’s like, ‘Please don’t think of me that way.’”

The family had attended every hearing they could in Shawna’s case. They raised the specter of their son in media coverage. They were quoted in multiple stories about the case as well as in stories opposing legislation around reducing youth offenders’ sentencing. They protested the sentence Shawna received. They drove the narrative around what happened to their son.

In stories since the sentencing, the Branhams repeatedly told reporters Shawna was convicted of a violent felony, which was not accurate. Reporters — without access to sealed juvenile records — repeated those descriptions.

Shawna was convicted of robbery. Had she been convicted of a violent crime, experts TPR consulted said the state would not have been able to seal her record as it said it would. It would have been unlikely to sentence her to treatment and release at age 18.

TPR’s request for Shawna’s records was denied.

“What was stated from the Branham family was that she was almost like the ringleader of all this,” Castro said.

The idea that a young girl called the shots in a room full of adult men with criminal records was laughable to a friend of Shawna’s from her time at The Refuge.

“She was around grown a** gangbangers. They know how to manipulate you. They’re perfect at it. And Shawna was a little girl,” said the former Refuge resident, who said she also was no stranger to gang activity.

“We’re kids — f***, she was a kid. She was a kid that didn’t know, and even if she knew she was influenced by those grown men.”

At the end of the day, the Branhams didn’t want Shawna dead. They wanted her to go to prison. The car accident robbed them of that.

Refuge

The Refuge for DMST (domestic minor sex trafficking) was one of the few facilities in the state licensed to treat victims of sex trafficking. Set among the wooded hills of Bastrop County, the idyllic ranch’s work had been celebrated by politicians and faith leaders and had successfully raised tens of millions of dollars in funding.

The Refuge provided Shawna with stability. The people around her saw improvement. Her grandmother commented on her gaining weight. She added 40 pounds. Her case manager said she rose through the facility’s levels of treatment, quickly attaining the most trusted level.

“I felt like I was getting my Shawna back,” Farris said. She made a series of seven-hour drives from the Oklahoma border to south central Texas to see her.

Shawna pictured at The Refuge feeding her horse, Lucy.

Courtesy Robin Farris

Shawna was one of the few girls who opted to work with the horses on the ranch. She spent months in equine therapy walking and feeding her horse before she could ride it. Her friends admired her dedication.

She didn’t get into fights, and her friends there said Shawna made everyone laugh. One former resident and friend recalled the two spent hours talking about their families (“Shawna loved her grandmother so much”) and what they wanted out of life. She was described by administrators as easy to work with and was succeeding.

But girls in treatment with her knew better.

“She just needed some hope. Just something to grasp onto,” said a former resident and friend of Shawna’s.

Despite her friend’s progress, two former residents said part of Shawna was working the system. Trying to get just enough freedom to take off.

Shawna didn’t see herself as a victim, which is common among girls trafficked for sex. She saw herself as part of Watford’s crew. Her trafficker was her “boyfriend.” She admitted she did not want to have sex with the men, but she had yet to reconcile the opposing ideas.

“At the end of the day, you were their scapegoat. You were their crash dummy. Because you’re a girl and because you’re a minor,” a friend in treatment recalled telling Shawna.

But Shawna didn’t listen.

She had something else on her mind, drugs.

What she needed was access to a phone. Phone and internet use was supposed to be strictly controlled at The Refuge. The use of a staff member’s phone is prohibited. The facility had a landline and youth had an approved call list. Despite this, one former resident who asked not to be named said it was possible to use staff phones.

“You just have to be able to keep that a secret and the staff had to trust you,” said one former resident who asked not to be named. “It’s honestly pretty f****** easy. Like… I went on a phone there multiple times.”

Shawna manipulated a staff member into letting her check her social media on the woman’s phone under a false pretense. She told the employee it had been hacked and she wanted to change the password.

Accessing her social media triggered old appetites and Shawna planned to run, said friends at The Refuge.

Castro said she and the staff member in question reported it to The Refuge before Shawna had run away.

Initially The Refuge said no staff phone was used to “call” anyone who assisted the escape.

In an email to TPR, The Refuge confirmed Shawna used the phone, but that they didn’t learn of it until “later investigations” took place.

A spokesman said Shawna used the phone only to reset her password. Two former residents said Shawna told them she was coordinating her escape.

The weeks of heavy drug use with Watford and the years of self-medicating before that had left Shawna addicted. Touching the conduit to her old life triggered old appetites. Shawna planned to run.

“We can’t have access to that because us girls there — as soon as we hit our social media, anyone will come pick us up at the gate,” one former Refuge resident explained. “We have so many bad people that we know that they’ll just come in. They don’t care where you’re at.”

Before long Shawna was coordinating with a man named “Tommy” who offered to pick her up in exchange for sex — according to other Refuge residents.

“Our belief that no staff members shared their phones as part of (Shawna’s) flight has been corroborated by the initial law enforcement investigations,” said a Refuge spokesman.

Shawna’s opportunity came in mid-August when Farris traveled to see her. The two planned to stay at a Bastrop hotel after spending the day together, as part of an approved overnight stay.

This was the fourth time Farris had been to see her since she was placed there in April 2021. Her father was scheduled to come, but bowed out as he had in the past. This upset Shawna. It was to be the first time they had an overnight stay together. The other times Farris had visited The Refuge, or taken her to town for hours, they had returned the same day.

One former staff member told TPR that it was unusual a girl would be granted an overnight visit so soon into her treatment — about three months — but Shawna was a dream to treat, The Refuge would later write of her.

On the night of Aug. 14, 2021, Farris said Shawna waited until she was asleep and then took her phone. She logged into her social media again and got Tommy to come pick her up. Screenshots of the messages confirms the account. Farris would not see her again until she was in the hospital.

The Refuge consistently denied accusations that Shawna escaped using a staff member’s phone. The organization went so far as to file a brief with the federal courtsaying it never happened, and the responsibility of Shawna’s escape lay entirely with Farris.

“The Refuge conducted an internal investigation to determine what may have contributed to her decision to run from her grandmother … it found no evidence of her calling an unapproved contact, either by using the cottage phone or by using a staff member’s phone,” read the court filing.

Former residents and Shawna’s case manager told TPR that wasn’t accurate.

“I really wish and pray that The Refuge would just be honest about what was really going on,” said Castro, Shawna’s case manager.

TPR reviewed screenshots that appeared to show Shawna’s phone was logged into her social media on a staff member’s phone. Other residents TPR spoke to said she started coordinating with it.

TPR could not verify whether that was a staff member’s phone or another device.

After she escaped, Castro spoke with the private investigator the facility hired to find Shawna. There was no doubt in her mind that everyone knew this happened.

The Refuge did not address the screenshots directly in an email response. They described staff members who made allegations as disgruntled. A spokesperson said a state investigation into whether staff assisted Rogers, found no evidence.

The spokesman said they have fired people in the past for letting youth use staff phones and changed policies to require all staff phones are to be left in the administration office — if the facility is allowed to reopen.

A former resident said The Refuge failed to act before Shawna ran away.

Her peers at the Refuge did not want Shawna to run. She would be out of state’s custody in less than six months, free and clear of her sealed record.

When one former resident said she couldn’t convince Shawna — she told the staff.

“They didn’t do shit. They asked her…But they didn’t really do anything about it,” she said.

Instead she was able to pack a bag, take money out of an account, and leave with her grandmother (who was ignorant of the plan) as staff and youth looked on.

A Refuge spokesperson said no one came forward with that information before Shawna ran.

“Several residents came forward during the following days to tell us she had been planning to run,” said Steven Phenix, a Refuge spokesman, in an email.

From The Refuge’s perspective, Shawna was not in its care at the time of her escape, and the responsibility lies with Robin Farris. Farris was unconvinced.

“Are they covering their ass because they didn’t know what was going on, or they did (know) and they don’t want to get into trouble?” Farris asked.

Another resident later gained access to another Refuge staffer’s phone, in part sparking an incident that fueled the explosion of scandal for the facility.

It was shut down in March 2022 over allegations that staff member Iesha Greene sexually exploited youth there, giving them drugs and then conspiring with them to sell nude photos of the girls using Greene’s phone.

The tumult drew federal court scrutiny, statehouse hearings, and an uncertain future for the organization that has often cast itself as the victim of media attention, misinformation and over-reactive state overseers.

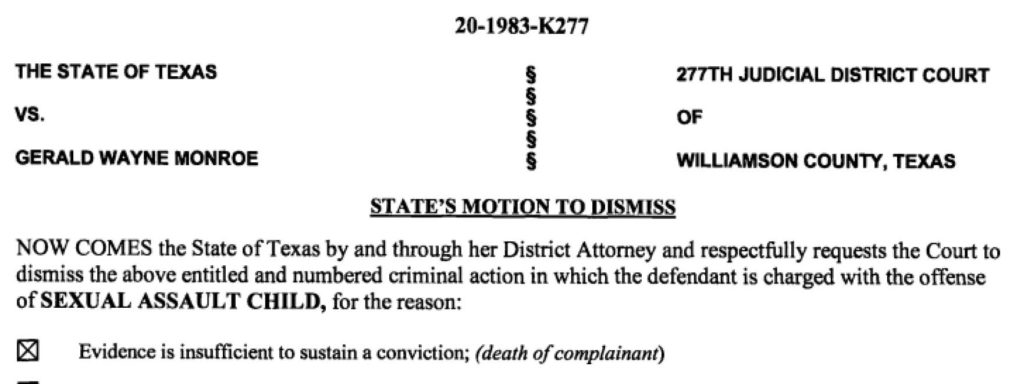

Without Shawna’s testimony, the case against Jerry Monroe was dismissed after her death.

Williamson County

Remnants

After Shawna died, the sexual assault case against Gerald Monroe was dropped. A single check mark gave the victim’s death as the reason on the dismissal paperwork. Unless new evidence emerges, Monroe will not be prosecuted. He denied anything sexual happened between him and his great-niece.

Prosecuting a child rape case without a victim is very difficult because most child abuse doesn’t happen in front of other people.

“She’s the only witness that the state would be able to call to prove the necessary elements,” said Kirsta Melton, the veteran prosecutor of child sex crimes.

One way to prosecute a case without a victim is to turn to digital evidence. But if police wait to arrest — as they did with Monroe, waiting eight months – the evidence is jeopardized.

“Then that digital evidence is very likely to be deleted or gotten rid of right prior to arrest,” Melton added.

The case against Chris Churchwell is a good example of a case against someone who allegedly assaulted Shawna that is progressing without her testimony. Messages and videos found on Churchwell’s and Shawna’s phone were all collected as part of the investigation.

Austin Police Department didn’t respond to TPR’s requests for comment but experienced prosecutors told TPR waiting eight months to arrest a perpetrator in a child sexual assault case is highly irregular.

“When you’re dealing with child abuse, that is one of the things we always move quick on,” said Nick Socias, who has prosecuted these cases for 12 years in Bexar, Harris and now Kendall County as a Special Victims Prosecutor.

You have to remove a suspected abuser’s access to kids, he said.

“A law enforcement agency taking eight months. I cannot see it. And again, I don’t know the whole situation. But that is a long time from activation to arrest,” he said.

The allegations against Monroe were made two weeks after the coronavirus pandemic shut down the nation in March 2020.

The summer that followed may have played a role as well. The officer who would ultimately arrest Monroe, Austin Police Detective Stanley Vick, was involved in the highly criticized response to Black Lives Matters protests. Vick was later indicted for his role and the case is pending. Vick did not respond to TPR’s requests for comment.

The CPS investigation continued and found “reason to believe” that Monroe had molested Shawna going back to when she was 8 years old in June 2020, according to court documents.

Farris blamed the lack of coordination between Austin PD, Williamson County, Travis County, and the Attorney General’s office for the failure.

“Why if y’all are all law enforcement agencies, is there such a disconnect?” she said.

Farris added that Connie Spence, who was prosecuting the case for the attorney general’s office, had repeatedly complained to her about the lack of evidence being provided by the counties.

Spence did not respond to TPR’s request for comment.

Jamil Watford and Jesse Perkins were not charged with trafficking. According to one person with knowledge, the prosecutor on the case — Victor Erbing — was solely interested in convicting Watford of the aggravated robbery alongside Kyle Cleveland and Anthony Davis with the murder of Chris Branham.

“It is well documented that around the time of the (Branham assault), (Shawna) was being trafficked by the other two defendants,” said a lawyer for The Refuge in a court filing.

The dearth of digital evidence seized — from the five cell phones to the five laptops — the transaction data from sex trafficking, and knowledge of other victims, makes a trafficking case winnable from a legal standpoint, a source explained.

Erbing did not respond to TPR’s request for comment. Neither did the Travis County DA’s office.

Branham’s parents, Conny and Jim Branham, plan to attend each of the men’s upcoming hearings, but they believed the lack of trafficking charges validated their beliefs about Shawna.

“If you say she was trafficked, when are you going to charge them with trafficking? ” asked Conny. “We’re still waiting on those charges.”

Shawna’s grandmother is also waiting but doesn’t have much hope.

‘How’s this fair to victims?’

An urn with the remains of Shawna Rogers sits in her grandmother’s front room.

Paul Flahive / Texas Public Radio

Shawna never regained consciousness after the October 2021 car accident.

When she arrived at Texas Health Harris Methodist Hospital in Fort Worth, her face was covered in grime and caked blood, and her hair was stained dark red with it.

Nurses had cleaned her up considerably. Half her head was now shaved on the right side.

A dozen staples ran the divide between her scalp and hair. A hole was created — a failed attempt to relieve the pressure inside her skull.

All that remained were light scars and scratches from where her face dragged across the ground along with marks from a surgical pen.

No brain function remained.

Police guarded her room, keeping an eye on the now braindead teen who was adjudicated for robbery. A lawyer had to go to court to have the police removed from her granddaughter’s bedside.

Texas was only interested in Shawna when she was a criminal, not when she was a victim: the lag in response to her abuse allegation (Shawna was arrested months before Monroe), the lack of trafficking charges for Watford, and the attacks by media via the Branham family.

The decision to end Shawna Rogers’ life at 17 was not an easy one. But nothing about the girl’s life had been easy.

Farris said there were no beeps or flatlining noises. Tubes were removed and Shawna was allowed to quietly pass away. An act of gentleness much of her life lacked.

Now, two years after Shawna’s death, the men that she said victimized her face no charges for their crimes against her.

“How’s that fair to these victims?” Farris asked. “That’s why they don’t come forward. Because they’re not going to get justice.”