At pivotal moments in our lives – often during moments of crisis – many of us will interact with doctors. They may be delivering a child, giving us bad health news or making a decision that could end the life of someone we love. All of those scenarios can be emotional for us as patients, but they can also be difficult for the doctor.

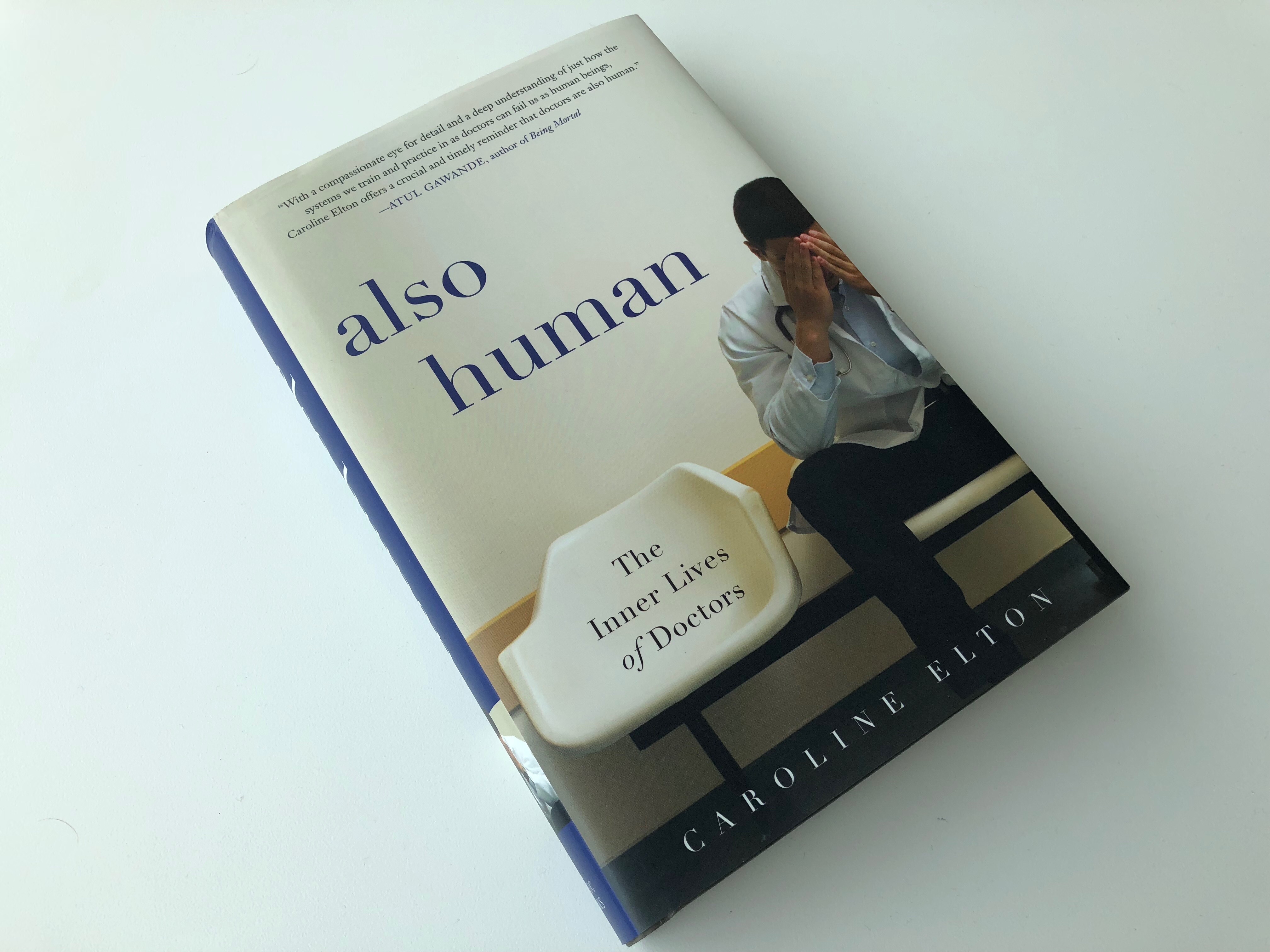

In her new book “Also Human: The Inner Lives of Doctors,” psychologist Caroline Elton draws from decades of experience working with doctors who are her patients – a specialty she got into purely out of happenstance. Elton says some of her patients choose their medical specialties to fulfill a personal mission, but their work can take a toll.

“In the book, I give examples of people who’ve lost a parent to cancer and they end up going into oncology or palliative medicine, and that can add a particular commitment and passion,” Elton says. “[But if] it feels too close – like one client of mine described it as scratching open a wound – then it can be problematic.”

Elton says the upside is that many medical specialities are broad enough that doctors can choose other types of work within that speciality if they are feeling emotionally taxed. For example, oncologists can focus more on training other doctors one week if they need a break from tending to patients. Some doctors learn to alter the balance of how they spend their time in order to make work more manageable. Others, she says, might end up changing specialities altogether.

Elton says doctors deal with a range of psychological and emotional challenges from their work. For one thing, they struggle with the pain and suffering of their patients, and, by extension, the suffering of the patients’ families. She says doctors feel extra pressure from patients and families to do more, even in situations when the doctor is powerless. Doctors also feel frustrated, Elton says, when patients don’t care for themselves in the way their doctor recommended. Doctors also struggle with their personal lives; many try to balance family life with years of medical school and post-medical-school training.

Elton says the patient-doctor relationship is at the heart of good clinical practice. That means that despite all their training, doctors can still be affected by their work, and patients need to be aware of that.

“We don’t know what they’ve just been doing before they come to interact with us because, obviously, that’s confidential. But they may have been doing some really difficult stuff,” Elton says.

She says if patients take a moment to remember that their doctor is also human, they will have a better relationship and ultimately will receive better care.

The correlation between medical errors and physician burnout is one reason Elton says patients should consider their doctor’s humanity – if not for their own sake. She says studies show that doctors who are burned out make more mistakes, and they also have less satisfied patients; those patients are also less likely to follow their doctor’s medical advice.

“There are numerous ways in which the well-being of the doctor ultimately will trickle down to the well-being of the patient,” Elton says.

Elton says she’s not alone in wanting more support for doctors’ health and well-being. But she says part of the problem is of their own making. That’s because doctors offer treatments for so many things like cancer, heart disease and infectious diseases – their work seems almost super-human, which makes it hard for patients to see them as people, with limitations.

There’s a worldwide trend, Elton says, that more and more doctors are experiencing burnout. She says it has been documented in places like the U.K and Western Europe, Canada, Australia and South Africa. She says that has happened, in part, because of increased demands on doctors without adding any support to counterbalance the emotional impact. For example, doctors can now keep alive extremely premature babies, but caring for them in such a delicate state is psychologically and emotionally taxing for all of the health-care professionals involved.

“Some of the successes of medicine bring with them very complex psychological and ethical challenges,” Elton says.

Written by Caroline Covington.

Support for Texas Standard’s ”Spotlight on Health” project is provided by St. David’s Foundation.