Singer-songwriter Nanci Griffith passed away on Aug. 13 at the age of 68. As the news spread across social media, colleagues, friends and fans praised her songwriting, her performances and her kindness.

Griffith wrote songs about small-town Texas life, including “Love at the Five and Dime” and “Gulf Coast Highway.” But just as often, her characters longed to soar off to places far from their homes as in “The Flyer” and “The Wing and the Wheel.”

Griffith, who was born in Seguin and raised in Austin, cut her musical teeth in the 1970s Texas folk scene, eventually winning the hearts of critics and fans from Austin to Ireland. She released 18 albums, recording her own songs, and paying tribute to writers she admired. And her tunes became hits – but not for herself. Griffith combined a delicate, winsome stage presence with a fierce dedication to songwriting.

Nanci Griffith adored words. Several album covers show her posing with books. Her Grammy-winning homage to the songwriters she loved, “Other Voices, Other Rooms,” was named after a Truman Capote novel.

When Griffith spoke and sang in her own voice, she mourned lost love, and made keen observations about the Texas she knew as a young person. And as her world expanded, her writing chronicled some of the hard lives lived by those she encountered.

Stephen Doster was one of her earliest collaborators.

“I came to Austin about ’75 and started playing at the Hole in the Wall on the Drag, and Nanci Griffith was playing there as well,” Doster told Texas Standard. “Her residency was on a Sunday night; I think I was on a Tuesday night.”

He says Griffith held her own in the Austin dive bar scene.

“She … suffered no fools when she would play the Hole in the Wall,” he said. “In fact, it was a pretty well-known thing that she was going to be telling the crowd to shut up.”

Doster played guitar on Griffith’s first album in 1978, and joined her in Nashville for her third, “Once In A Very Blue Moon,” six years later. By then, Griffith had a record deal with folk label Rounder, and a lot of friends and musical collaborators to call on. Her acoustic sound had been amped up a notch, with stalwart Nashville players like Béla Fleck, Roy Huskey Jr. and Mark O’Connor – and a lanky guy she knew from the Texas music scene named Lyle Lovett, singing harmony. Doster played acoustic guitar, and taught the Nashville band Griffith’s songs. She called him her “musical director.”

“Of course, after that, things really took off for her even more so,” Doster said. “I would like to think that the ‘Once in Very Blue Moon’ record and her first Austin City Limits performance was a big jump for her, thanks to all those fine people.”

Beginning in 1985, Griffith performed on the PBS show, “Austin City Limits,” eight times.

Griffith didn’t write the title song from “Once In A Very Blue Moon,” but she made the Pat Alger tune her own – so much so that the band she formed in the late 1980s, and toured with for 20 years, was called the Blue Moon Orchestra.

It happened again with “From A Distance,” the Julie Gold-written song that Griffith was first to record. That version inspired Bette Midler to record it too, spawning a giant hit.

Many consider Griffith’s 1986 album, “The Last of the True Believers,” to be her masterpiece. It includes the iconic “Love at the Five and Dime,” which tells the story of a Woolworth’s cashier who falls in love with a musician, and their life together. The song would go on to be a breakthrough hit for Kathy Mattea. On the “True Believers” album cover, Griffith stands in front of Austin’s Woolworth’s department store, which would soon be torn down to make way for a 21-story office building. Lovett is in the crowd behind her.

Griffith left Austin for Nashville in 1985, and signed with MCA Records. Doster says she always had success on her mind.

“What most impressed me about her was her work ethic and her drive,” he said. “We would have a good time at shows and stuff. But she was very serious-minded about what she was doing. When we did work together, it was always with a plan in mind and she was moving that boulder down the road with everything she did.”

She worked with producer Tony Brown on her next few albums, and that connection would give Griffith a chance to help another Texas artist. Singer Kelly Willis was just starting out when Griffith caught her show at Austin’s Continental Club around 1989.

“She got on the pay phone – nobody had phones back then – and called up Tony Brown, her producer, and said, ‘You need to get down here; I think you’d like this girl,’” Willis told Texas Standard.

They only met once, but Willis says Griffith changed her life.

“That definitely played a huge role in my eventually signing to MCA, and getting to make music with Tony Brown,” Willis said.

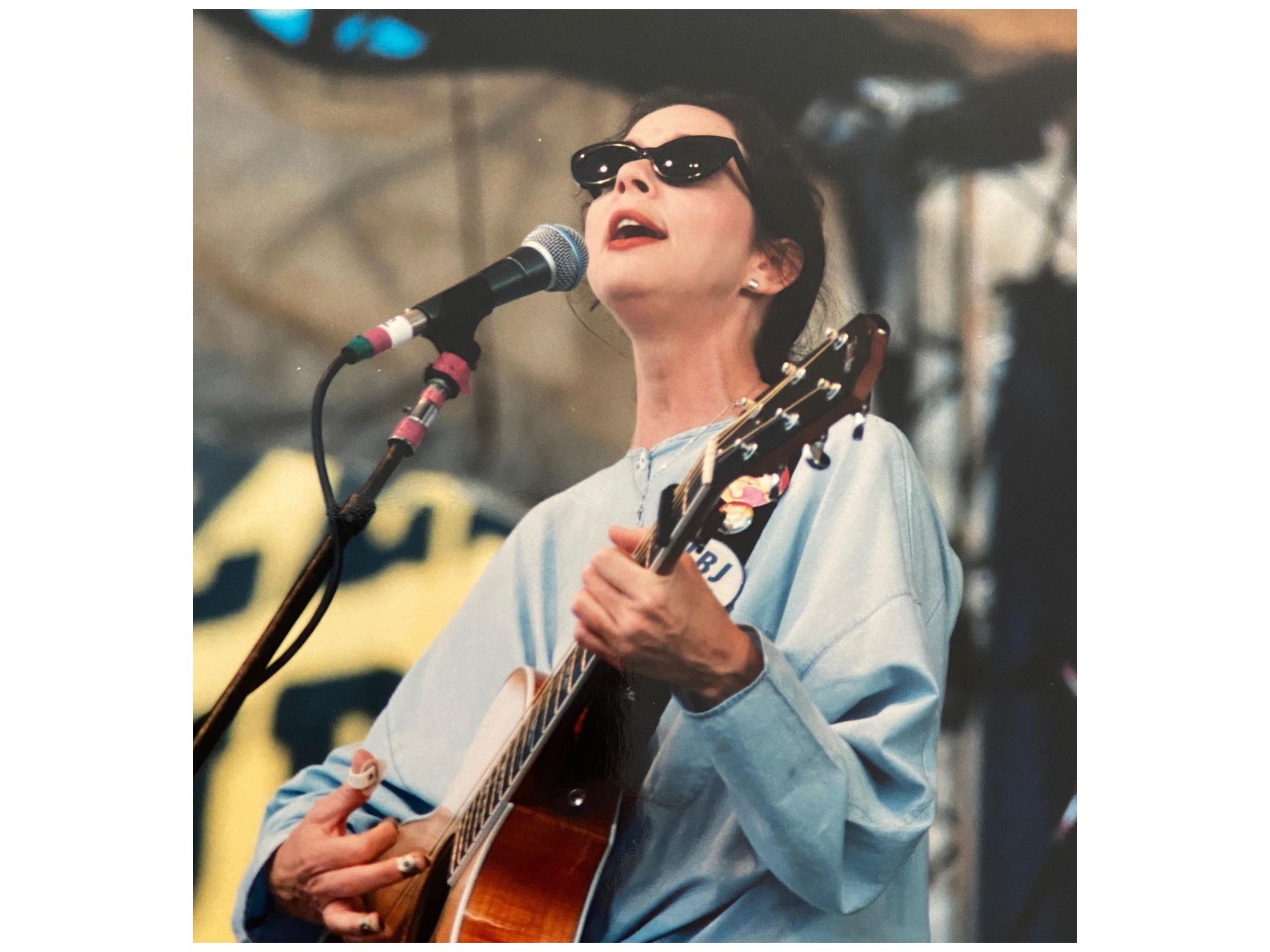

Nanci Griffith performs at the Newport Folk Festival in 1993

For Mary Gauthier, Griffith’s generosity took physical form, sometime in the early 1990s. At a Nashville party, Gauthier and Griffith were part of a group of writers swapping songs. Gauthier had just moved to Nashville to try her hand at music.

“I was handed her guitar and asked to play a song in the song circle,” Gauthier said. “And when she handed it to me, I did play. And then when I was done, I handed it back and she said, ‘I don’t think so; I want you to keep it.’ And she gave me that Taylor with that, that sunburst cutaway that you see in all those pictures.”

The guitar had once belonged to Harlan Howard, a songwriting hero of Griffith’s, who had given it to her.

For Willis, Gauthier and other women trying to forge music business careers, Griffith was an inspiration.

“She was a trailblazer for women,” Gauthier said. “And her hero, her role model, was Loretta Lynn. And I think she loved Loretta because Loretta wrote her own songs.”

Terri Hendrix first heard Griffith on “Live at Anderson Fair,” a 1988 album recorded at the legendary Houston folk club.

“My guitar teacher wanted me to hear it because [Nanci] was a great guitar player,” Hendrix told Texas Standard. “And I was trying to improve my guitar chops, and he felt she would inspire me. And then, what also inspired me was her lyrics. And it was that record – that live record – ‘Live at Anderson Fair.'”

In 2006, Hendrix shared a bill with Griffith and Judy Collins in New York. She says she was still learning from the way Griffith played.

“Her right hand, when she would strum: total control,” Hendrix said. “As an encore, we did ‘Not Fade Away,’ And she just totally held us down like a drummer.”

Over the years, Griffith’s sound evolved. In 1993, she moved to Elektra Records where she felt free not to pursue country stardom. She collaborated with Hootie & the Blowfish and the Irish group, The Chieftains. She became a huge star in Ireland, and spending time there led her to write “It’s a Hard Life Wherever You Go,” a song about the Troubles – the 30-year conflict in Northern Ireland – and prejudice in America.

Not everyone was taken with Griffith. Some critics complained that her singing and her stage patter were affected and “precious.” Hendrix believes Griffith made artistic choices to sound the way she did, sometimes emphasizing the childlike quality of her characters, and sometimes embodying them at a deep level.

“As an artist, there’s this parallel between light and dark,” Hendrix said. “And I think she danced on that razor’s edge. And I think part of that little girl voice was part of that; the deep little girl inside of her.”

Criticism hurt Griffith. In 1999, she famously penned a scathing letter to Texas music writers, denouncing what she felt was shabby treatment, and writing that Texas was “the only place on Earth that actually eats its young.”

Michael Hall got Griffith’s letter and wrote about it in Texas Monthly, amplifying some of the criticisms of Griffith. Today, Hall says he probably “piled on” in response to the letter. For Griffith’s fans, the incident is still a bit of a sore point.

Nanci Griffith in 2011.

Nanci Griffith survived two bouts with cancer in her 40s, and returned to performing. But in the past decade, she receded from the music scene. She released her last album, “Intersection,” in 2012.

There’s a tribute record in the works – delayed by the pandemic, but due in 2022. Mary Gauthier has recorded a song for it.

For her fans and fellow artists, Nanci Griffith’s legacy is secure as a gifted songwriter.

“She was just a good, good, good songwriter. And she captured the time that she lived in, which is, I think, the greatest thing any songwriter could do,” Gauthier said.