For asylum seekers, the way their story is presented to the immigration courts can quite literally be the difference between life and death.

In order to prepare for a court date, those who are lucky enough to have a lawyer guide them through the overwhelmed U.S. immigration system must relive, again and again, the emotional trauma that sent them to seek asylum in the first place. And that court date is likely to be postponed months, sometimes years down the road – which often leads to weary asylum seekers contemplating giving up.

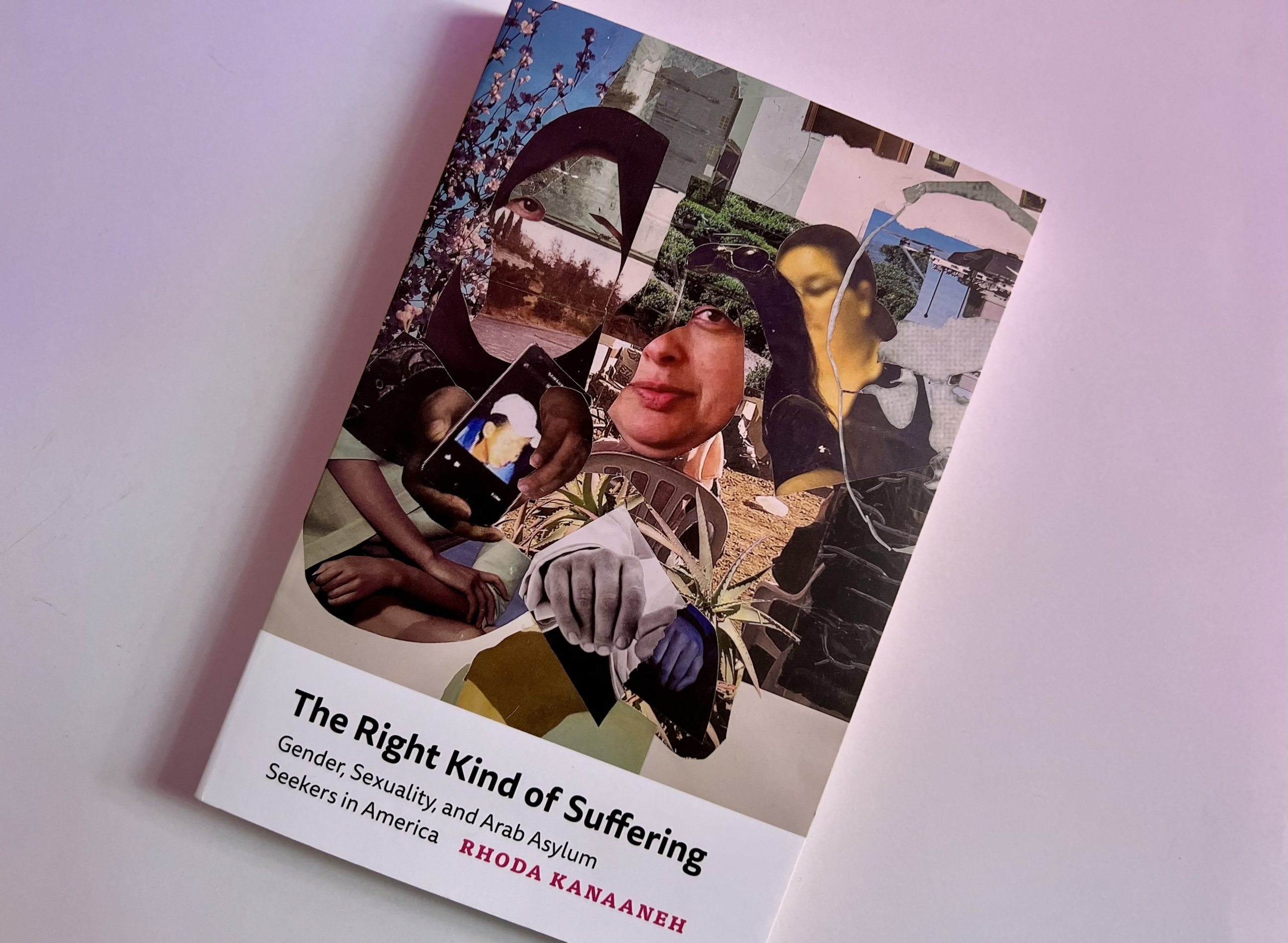

It’s as if it’s almost by design, notes Rhoda Kanaaneh in her new book, “The Right Kind of Suffering: Gender, Sexuality, and Arab Asylum Seekers in America.” She’s an anthropologist and also a former Arabic interpreter, volunteering her services to asylum seekers for over a decade. Kanaaneh spoke with the Texas Standard about being an interpreter for asylum seekers, writing the book in a tumultuous time for immigration policy and what readers should take away from her book.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: As you know, in Texas, we see a lot of asylum seekers entering from Mexico. They present themselves to Border Patrol, hoping to plead for asylum, and it’s become significantly harder since 2016, as you note in your book. The four asylum seekers’ stories, though, in your book are different from the sort of stories that you encounter on the southern border – you say not just because of time, but because of privilege, which feels odd to say about anyone fleeing their home for a safer place to live. Could you say more about that?

Rhoda Kanaaneh: Well, the asylum seekers that I met had the privilege of having an attorney, which a lot of asylum seekers do not have. So they were able to receive the very important guidance of legal counsel to navigate a very complicated and convoluted system, which greatly improves their chances of success. So in that sense, they were privileged. They all arrived here not by presenting themselves at the border, but by entering with visas, student visas, tourist visas, etc. So they were able to enter sort of less on their back foot than people presenting themselves at the border in the south.

This is a tumultuous time for U.S. immigration policy. Why did you want to write this book now?

I started to write it well before the current sort of asylum-focused moment. And at the time I was very interested in the kinds of stories that the immigration system and our larger political system likes to hear about immigrants and who it wants to welcome into the country. As my research dragged on quite a bit, partly because the cases took so long to decide, the political shifts made the subject more and more important or significant to the wider public. So it was an unfortunate development for the world, but fortunate for my book.

I want to talk about the four people that you focus on in your book, the sort of case studies, in a sense. They’re complex stories, but they have to be somehow communicated to the immigration judge, right? And that judge is making determinations based on, well, unofficial, perhaps you could say, parameters and certainly biases. Is that what you’re getting at when you say the ‘right kind of suffering’ in your title?

Well, one of the things that asylum seekers have to communicate within a very short period of time that they have in front of the adjudicator is both the persecution that they suffered and the pain that they experienced. They need to communicate that in a way that is the most legally impactful. Therefore, avoiding talking about the poverty or any economic aspects of their persecution or their migration to the United States, and they have to sort of resurface emotions that they’ve been trained to dull over practice periods with their attorneys because, you know, they’re lucky enough to have the attorneys to help them prep.

They’ve sort of dulled their emotions so that they can be able to withstand the stress of an adjudication while remembering all the details that they need to remember, in particular sequences and particular dates, etc. But then they’re encouraged to resurface their emotions in the moment, because the adjudicators are told to make their decisions based on appropriate demeanor of the asylum seeker, whatever that means. And that’s a very subjective thing of course.

I’m curious, what does that mean, ‘appropriate demeanor,’ and how does one even prepare for such a thing?

Yes, it’s quite a mind game that compounds the traumatization that is part and parcel of the asylum process, unfortunately. They have to sort of guess at what would be the right way to respond across cultural divides and to communicate to the adjudicator that they are being truthful and that they have been a victims of traumatization.

That must be a real challenge for you if you’re serving as in that role as interpreter, to communicate that sense that will strike the right sort of tone or note, I guess?

My role was as interpreter only for sort of affirmative asylum cases where the asylum seeker can bring their own interpreter. In the case of courts, there’s a court-appointed interpreter, which I am not. But my role was to sort of instinctually try and calm the asylum seekers through this very stressful period and to sort of be a witness to what they could not communicate outside of the court.

Surely you’ve been following what’s been happening at the southern border, and I’m wondering how your experience informs the way that you think about what is happening there?

I can’t imagine what it would be like to sort of have these rapid encounters that asylum seekers at the southern border must be having, if they’re lucky to have them.

I had a sort of a personal experience with my father, who had applied for a green card. It was delayed significantly because he was Palestinian and Muslim; we discovered he was under a prolonged security background check. In the meantime, he had to apply for this document that allowed him to travel in and out of the United States. And one time when we were traveling together as a family, the person at the airline didn’t recognize the document. And the document says, you know, this authorizes the traveler to enter the United States. And they decided that this document does not authorize them to board the airplane.

And that personal experience was incredibly frustrating. We were able to overcome it because of our contacts and our ability to absorb the cost of this experience. But it made me think about how complex and difficult it must be for people crossing the border, not only because of the difficult rules that they must abide by, but also the misapplication of rules, and then misrecognition of documents that they may or may not have.

What are you hoping people will get from this book? What are you hoping that people will walk away from it with?

I hope that they can walk in someone else’s shoes for a short time, to think about what it might be like to be an asylum seeker, with all of the history and difficulty that comes from. And I think that some of the stories that we hear in media are oversimplistic and demonizing of people who really we should be able to sympathize and understand and empathize with.