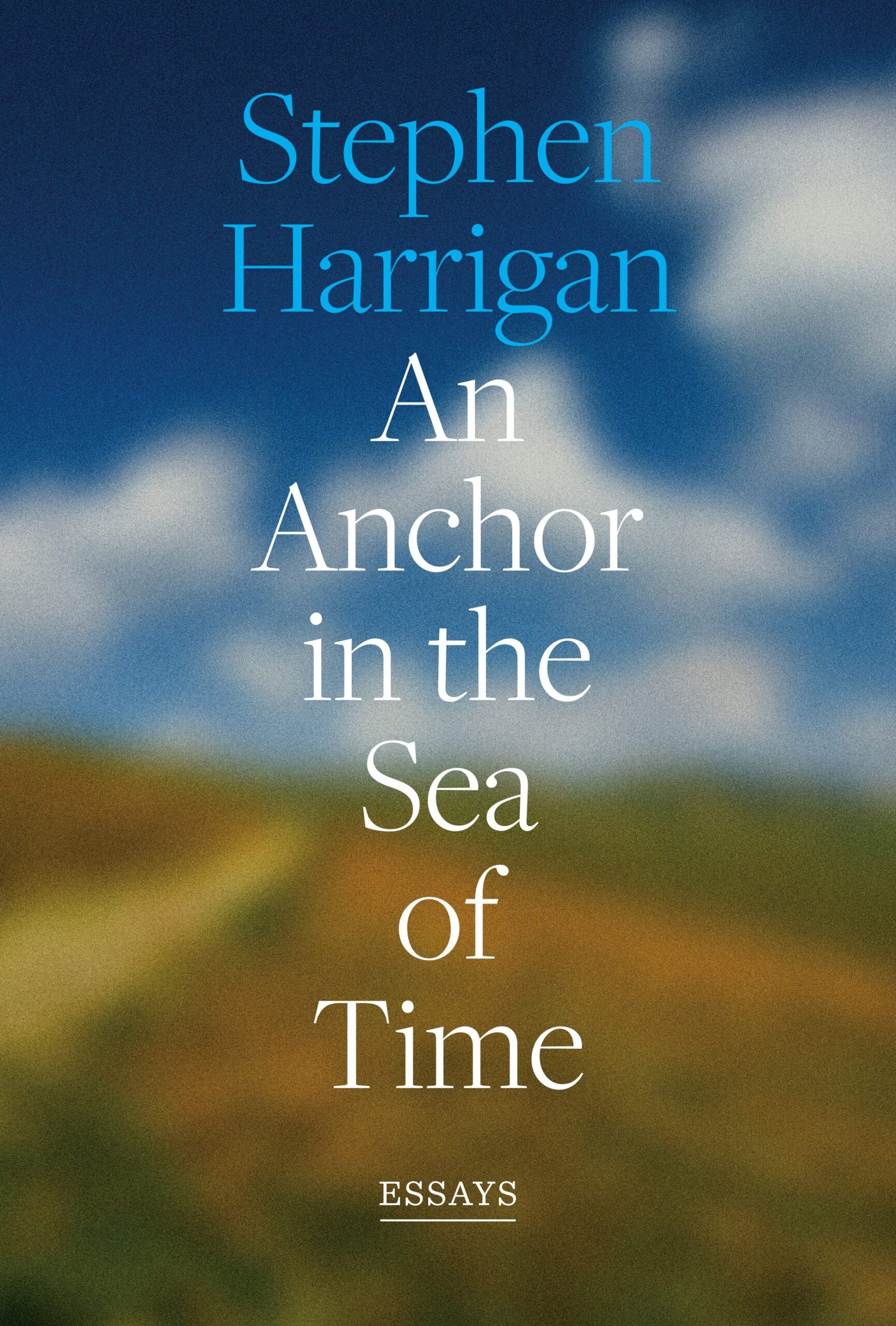

Stephen Harrigan’s new book, “An Anchor in the Sea of Time” might look modest next to his sprawling works like “The Gates of the Alamo” or “Big Wonderful Thing.” But don’t be fooled – this collection of essays spans vast territory: history, memory and how Texans make sense of both.

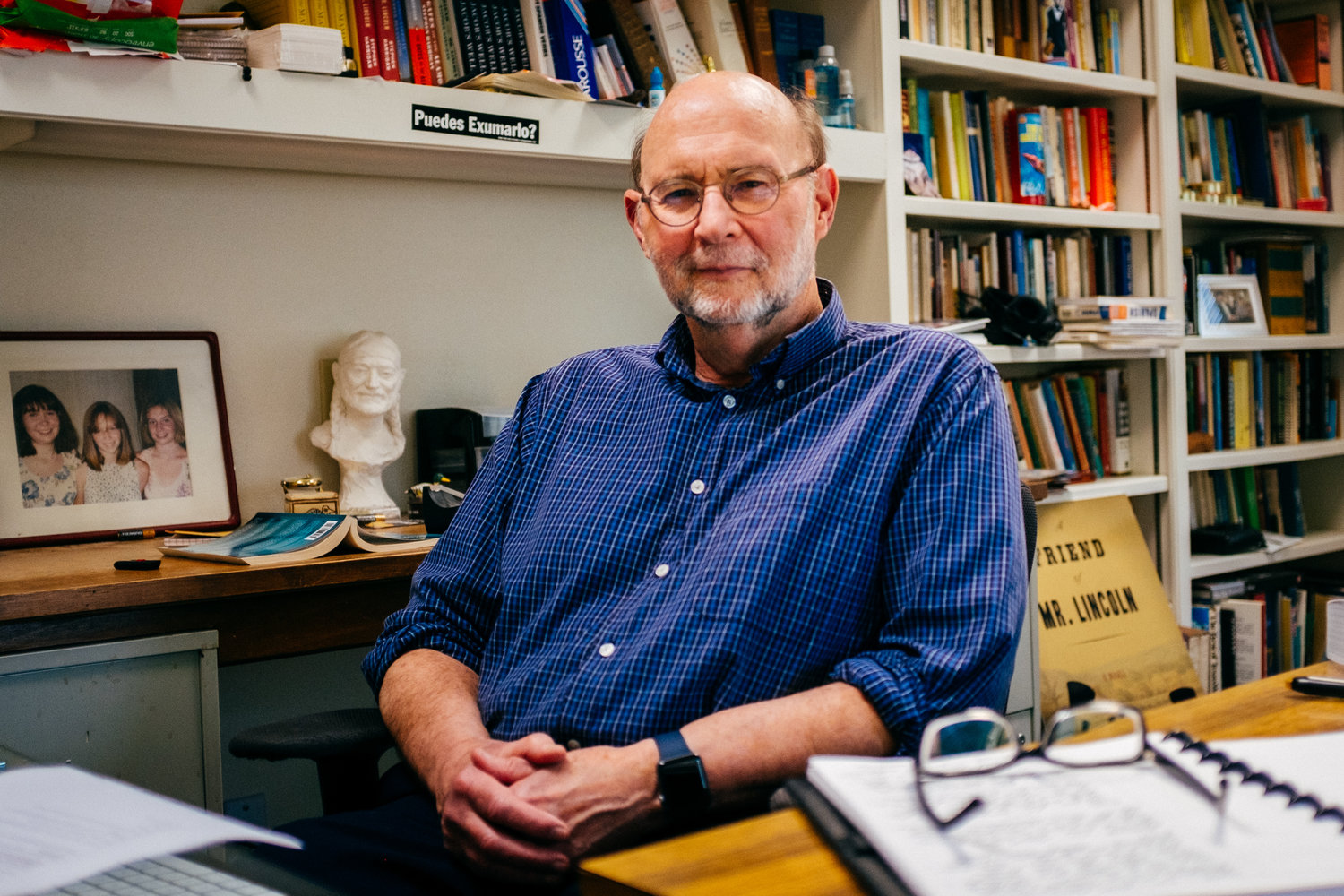

Harrigan spoke with Texas Standard about the moments that anchor us, the myths that define us, and how searching for his late father led to surprising discoveries about the truth and his vision of Texas. Listen to the interview above or read the transcript below.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: Collections of essays – and I’m sure you know this – can sometimes feel like a bit of a grab bag, but this has so much more of a deep narrative throughline. Do you remember a moment, the spark, that told you you wanted to write this book, “An Anchor in the Sea of Time?”

Yeah, I do. I think maybe it was 2016, 2017. I wrote all of these pieces – except for one, which was in The Alcalde, the UT alumni magazine, edited by my daughter, Dorothy Guerrero – all the other pieces were published in Texas Monthly. And I wrote a piece for Texas Monthly about a search for the father I never met.

It turns out it involved a lot of mountain climbing because I went to the site where his plane had crashed before I was born. But after I wrote that, I realized that this combination – for me, at least, of memoir and deep reporting – led to a kind of new field for me. And I began to think with each new piece I wrote after that, that I wanted it to – for want of a better word – harmonize with everything else I was writing.

So you rightly mentioned that a collection of essays can be a grab bag. This is not meant to be that. It’s meant to be kind of thematically coherent, even though each piece is completely different from the others. But there is a sort of shared awareness in all of them, I think, of, as you said, time and identity – and the reality of time and the reality of history itself.

The last essay in this collection takes you back to when you were 12 years old. There was this idea – and it wasn’t a particularly significant event or anything – but you had this sort of awakening as a kid that this was something that you needed to hang on to, that you needed to remember. And it’s something that I think a lot of us have experienced at one point or another, where there’s just almost this small voice that says “remember this.”

Could you say a little bit more about that and why that was so powerful to you?

Yeah, as you said, it was not a significant event. In fact, it was a non-event.

I was riding in the backseat of my parents’ car, and I think we were driving probably from Abilene or Corpus Christi to my grandparents’ house in Oklahoma City. And it was wintertime, and we were in a kind of desolate part of North Texas. And I was looking out at basically nothing. I was sitting there.

For some reason, I decided, okay, I’m going to remember this moment for the rest of my life. I mean, it was totally arbitrary, totally random. But I felt the need to put down a marker, I guess, or as the book’s title says, an anchor.

Because even at that age, I realized that my memories were going to slip away sometime, if not immediately. And there was an imperative to try to grab onto something, anything – you know, whatever life raft I could, or life buoy, or whatever I could find – that would just make this moment of my childhood last.

And, you know, every once in a while, lo these many years later, I would reflect on that moment. What caused me to do that? What kind of awareness did I have at that moment that time would slip away and memory would slip away?

But in a way, I think a lot of my career as a writer has been trying to catch up, in a way, to the experiences I had as a child and also to the experiences that I could not have had that took place before I was born. But there’s a sort of need, I think, I have to make things feel real to me and, I hope, to the reader.

I was going to ask why you thought that memory endured when, you know, obviously many others would have faded away, things that we just don’t remember. And I’m curious, why do you think that was?

I was going to ask why you thought that memory endured when, you know, obviously many others would have faded away, things that we just don’t remember. And I’m curious, why do you think that was?

And I wonder too, given your career, your life as a journalist and as a writer, if in a way there was this yearning for a pretty deep idea of what is actually true. You know, what is it that we are here for, in a sense? You know what I mean, or do you think I’m too off the mark there?

No, you’re not off the mark. I can’t claim to be as cosmically aware as that might imply, but I do think, you know, I think children of that age, let’s say 12, are starting to become aware that they’re no longer children and that there’s a world ahead, there is a lifetime ahead, but there’s also a lifetime behind.

I don’t know that I consciously was able to make that conclusion to myself, but unconsciously the notion that I could hold onto my identity, I guess, had something to do with holding onto memory. And so here I am, just this ordinary kid, with acne and glasses, sitting in the back of this car in this extremely ordinary landscape with nothing to see.

Maybe it was the plainness of everything. Maybe it was the lack of beauty or the lack of landmarks or something that sort of stirred me in a way. And I’ve always felt, as a writer and as an observer, I guess, that the sort of unacknowledged places are often the most interesting – the least beautiful places, the least noticed. There’s always something fascinating going on in those places.

A big part of this, you seem to sort of hint at, are those things that have been forgotten, overlooked, or almost rewritten from memory. And there’s a famous essay in “An Anchor in the Sea of Time” regarding the Karankawa tribe, an Indigenous group reclaiming its identity. It seemed like it really resonated with your own efforts to reconstruct your personal and family history.

In a way, yeah. I mean, certainly the story is about the Karankawas and their their efforts to sort of throw off the myth that they were extinct and to kind of reclaim themselves both as a tribe and a people and to reach out to one another to reconstruct, in some way, their history.

But their history coincides with other people’s history, and one of those people is me, because I grew up on the Texas coast, and I grew infatuated with the historical myth of the Karankawas as vanished people. I mean, that’s not true, and it’s not true that they were cannibals – or at least they were ritualistic cannibals, as a lot of Native American tribes were. But they didn’t eat people for food. They weren’t seven feet tall.

All these myths that kind of excited me as a kid, which turned out not to be true, but in a way turned out to fire my imagination for what the real story was of these people, of the place they lived. And that led inexorably, I think, in my life to being curious about Texas itself and what its history is and what really happened and what didn’t.

What you just said there reminded me of arriving at the Austin airport many years ago, and I think I was heading very quickly to the bathroom getting off a flight.

That’s what we do.

And there was a little, it was like a little plaque, and it was, I don’t know what the purpose of it was. It may have been just decorative, but it said, you know, it had a little emblem of Texas in it and it said “Memory, mythology”… Something else that was alliterative, I’m sure.

And I thought about how much mythology is celebrated, certainly in the Texas story, and a lot of Texans obviously celebrate a lot of mythology as well. And I wonder, there is an argument to be made that, in a sense, mythology kind of takes over and that the truth doesn’t just get lost, but it becomes really part of that sense of identity that we all sort of carry around with us.

And what do you think of the notion that that’s okay? I mean, there have been some people who have made this case that it’s not just about the literal what has happened or what happened, that mythology takes on a life of its own.

I think mythology creates history just as much as history creates mythology.

Is that okay? I mean, should we be – I mean, I know that, but there’s something that sort of gnaws at me about this idea that mythology does sort of wipe out whole groups of people. The stories aren’t told and they are forgotten. Just wondering what you make of that.

It’s a big and interesting question, you know, because mythology is what defines us as much as history, and that mythology can be great or it can be toxic. But it’s inevitable, it seems to me, that just as human beings seem to be hardwired in some way for religion, I think we’re hardwired for making stories out of the facts or the rumors of the past and presenting those to ourselves.

And, you know, as a historian, which I guess I kind of am, and as a journalist, you know, it’s all about the facts. And so you’ve got to get those right and you’ve got to delve beneath the myth, but you can’t throw over the myth because that’s a defining element of what very often brings you to that curiosity in the first place.

And so I think they’re embedded in each other, history and myth, and we just have to accept that, but we can’t rely on that, I guess, in terms of our own intellectual development.

» GET MORE NEWS FROM AROUND THE STATE: Sign up for Texas Standard’s weekly newsletters

But it also seems so important to the here and now, especially as we talk about, you know, the statues that we have, right? What we think of when we call ourselves “Texan.” All of these much bigger questions that are such a big part of the current, even political conversation.

Not being able to agree on the facts has some pretty profound implications for the way we see ourselves and the way we see our future, it seems to me.

Oh yeah, I think as we’ve experienced, you know, agreeing on the facts is the baseline for a workable society. And I think we’re in deep trouble right now as a country because there was that famous phrase, “alternative facts,” that has entered the bloodstream of our national, and probably, global identity. And I don’t know how to purge that idea out of us because it’s so dangerous.

But I guess the only thing is to keep looking for the facts – for the real facts, not the alternative ones – presenting them and just doing the best you can to give some perspective to those facts so that they don’t just seem like things, but they’re living, breathing elements of our history.

I want to loop back to that first essay, “Off Course,” where you’re reflecting on the father that you never met. Did you feel that you were able to find your father in thinking about the memories or trying to connect these different aspects? Were you able to get closer to the truth, do you think?

Yes, I really feel like for the first time in my life I understood who he was and who he had been.

And partly that’s because for most of my life – I mean, he was a fighter pilot in World War II and died a few years later, before I was born, in a training accident in the Pacific Northwest – part of the way of dealing with trauma in that generation was not to talk about anybody too much. So we didn’t grow up, my brother and I, knowing anything about our father except what we could catch on the fly from conversation.

And it was after my mother died that we decided, well, we need to know this guy because this is the foundational identity of us. So Jim, my older brother, and I, and my younger brother, Tommy, who had a different father but the same mother, we went to this mountain, Mount Pilchuck, in the Cascades in Washington State, and climbed up to the site where his plane had crashed.

Along the way, I contacted the families of the other two people who died in the crash. So we had this wonderful sort of reunion, if you could call it that, with the descendants of those two people. You know, we went through letters and diaries and all of us, I think, learned about our relatives.

In one case, it was their uncle, and in the other two cases with my brother and me, it was our father. And, you know, you can’t say we came face to face with him, but we did really come close. We went to the Army base, or the Air Force base, where my mother, who was an Army nurse, and my father met. We stood on the grounds of the now torn-down hospital where they had met, and she had met him while he was recovering from malaria.

We read through many letters, my mother describing this guy, Mac, that she had met, that she really was dazzled by. And so it was as close as I could have imagined getting.

And yeah, I’m still curious. I see features of him in my grandchildren and in my nephew, and to some degree in me – physical features. And so there’s a kind of never-ending story there, at least in terms of genetics, that is interesting to me as well.

One of the reasons I wanted to loop back on that is because to the extent that we are trying to get to what is real, I wonder if there’s not a prescription there somehow – that to the extent we are willing to chase down those threads of memory, that it’s a journey worth taking.

You know, one of the things that’s not in the piece that I wrote, but happened later, was my father was shot down in the Pacific during the war and was in a raft and was about to be captured by the Japanese on this island where he would have certainly been tortured to death. And a heroic crew of a PBY, a flying boat, came and picked him up under intense enemy gunfire.

And I started to think, I wonder who those people were. And I did some digging and I found out the name of the captain of the plane that had rescued my father. And I found that his wife was still alive at almost 100 years old.

So my two brothers and I got on the phone and called her and told her thank you. And she remembered it. She remembered that incident – her husband had told her about it.

And what I took away from that is, you know, there’s kind of always somebody to say “thank you” to. There’s always more digging to do. And if you just keep turning over rocks, you’ll find something fascinating and also something deeply satisfying.

Stephen, what do you hope that people reading this collection of essays will ultimately walk away with?

You know, I never think so hard about that. I guess I just hope that if they choose to read it, they’ll find it illuminating or entertaining.

I guess entertaining is probably the first order of business, that they have a momentary relapse from checking their social media on their phone or watching Netflix. But I do think there’s something in here that all of us can relate to, and I think that’s why I wanted to create this collection, because even though it’s a very personal book, I hope it’s personal in an expansive way that other people will understand and recognize.