As the national arm of the Democratic Party targets Texas’ rapidly growing and changing suburban districts, various voting groups could play a role in efforts to flip some reliably Republican seats. One of those groups is suburban women voters.

Until three years ago, Ana Maria Ramos could be counted on to help her Richardson neighborhood association. A life-long Democrat, Ramos was always ready to lend a hand with local party efforts. But she says Donald Trump’s election three years ago pushed something inside her.

“I actually was so furious that I ordered political yard signs that I made up myself. They were black and bold letters that said ‘Resist Trump,’” Ramos says.

Ramos was certain there would be backlash from her suburban neighbors after she put one of the signs in her front lawn. Richardson lives in solidly blue Dallas County. But a portion of the city lies in Collin County, a historically Republican stronghold.

Far from angering neighbors, Ramos was surprised to find out that her signs acted like a beacon. Like-minded political newbies came to her door. And from there, a bigger local coalition was born in her suburban living room.

“It was after that that through our movement and our passion for just fighting for our neighbors, that it just became, what I call now, it became a spiritual revolution,” Ramos says.

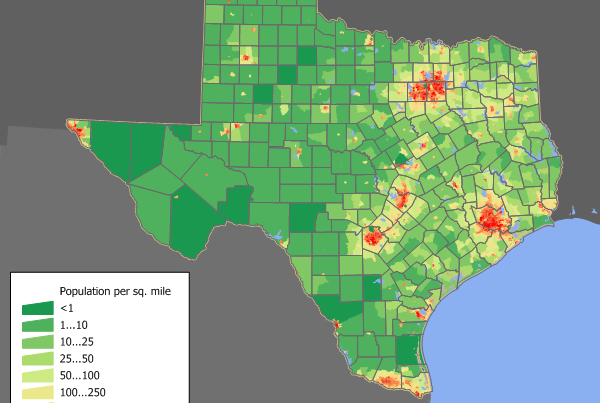

For the past three decades, the neighborhoods near where Ramos lives have mostly been Republican. But recently, House District 102 has become a more competitive seat. The district includes Dallas County suburbs that have seen rapid overall growth and a much more diverse populace since 2009. That shift could make this district less of a GOP sure thing.

And what’s happening in North Texas is also happening in other growing suburbs across the state.

Rebecca Deen, chair of the political science department at the University of Texas at Arlington, says this trend was more visible in last year’s elections in North Texas and across the state.

“Certainly, we have seen in the past couple of election cycles, especially 2016 at the national level, a movement of predominantly white women, who are married and with kids who might have in the past supported a Republican candidate uncomfortable with candidate Trump,” Deen says

She says women living in those suburbs are a key factor in this possible political shift.

In Ramos’ living room, her fledgling political group started taking a closer look at their lawmakers. As they learned more about their state rep’s voting record, Ramos and her group felt even more unsettled.

“It was very anti-immigrant, very anti-LGBTQ… and which is what we were resisting right?” Ramos says

And that pushed Ramos, a lawyer and community college professor, to take a bigger political leap. Overnight, the living room where she had her activist meeting became her campaign headquarters.

“I said, ‘guys, I’m gonna run for office. I don’t really know what this is all about, but I’m gonna do it,’” she says.

Last year, Ramos won her race against Republican incumbent Linda Koop by five percentage points. Ramos was heavily out-spent by Koop. But she credits her newfound political success to women living in her district.

“I could not have won it without the support of the suburban women,” Ramos says.

Some of the core voting issues for suburban women right now are education and health care, says Elizabeth Simas, a political science professor at the University of Houston.

“So in general a lot of the issues that women on public opinion surveys would rank as their most important issues again tend to be more of the bread and butter Democratic and liberal issues – stereotypically the things like education, health care, the social safety net,” Simas says.

And Simas says that as more college educated, employed women choose the suburbs over living in the city for more affordable housing, they’re bringing their political ideology with them.

“I am a suburban mother. I am a suburban woman right now,” Simas says. “But again, I think I am also an example of that changing demographic. I’m educated, I’m employed, I’m not necessarily that 1950s housewife that just votes the way my husband tells me to.”

UT-Arlington’s Rebecca Deen says this group historically leans Republican.

“In general we think of them as Chamber of Commerce Republicans,” Deen says. “So fiscally conservative and socially more moderate. Not liberal, but perhaps more moderate.”

So, if suburban women seem to be shifting their votes from red to blue, what do Republican candidates do in 2020?

Randan Steinhauser is a Republican strategist based in Austin. She’s sounding the alarm for her party.

“We as a Republican party need to better connect with these women voters,” Steinhauser says. “I think more than anything, we’ve got to connect with the women at the local level and make sure they understand that Republican policies are for supporting small businesses, supporting entrepreneurialism, limited government, lower taxes, making sure they understand our desire to have strong education opportunities for families.”

Steinhauser says the Republican Party needs to field stronger women candidates in general.

“Until we have strong conservative women candidates running for office that suburban women can identify with, that they can sit down and have a glass of wine with, or talk about the neighborhood school with, or understand the issues that affect suburban women. It’s going to be very difficult,” Steinhauser says.

Three Central Texas congressional districts currently held by Republicans are being targeted by the national Democratic party in 2020. One of those races is for Republican Congressman John Carter’s seat. Last year, Democratic candidate M.J. Hegar came within three percentage points of unseating Carter. Hegar has now set her sights on unseating longtime U.S. Senator John Cornyn.