From KERA:

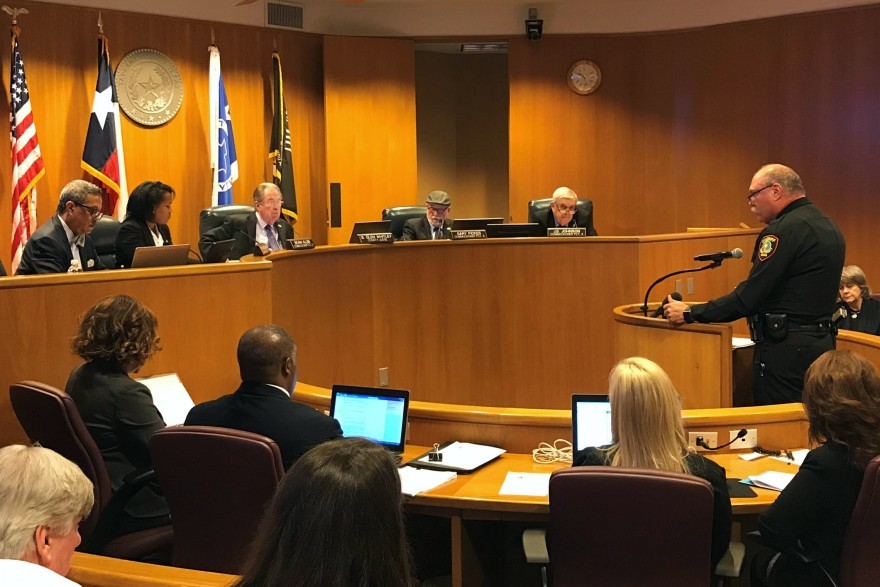

Last year, Tarrant County commissioners renewed a controversial immigration program, and got rid of its expiration date.

The 287(g) agreement allows local sheriffs’ deputies to carry out some of the responsibilities of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents. They identify undocumented inmates in the Tarrant County Jail and flag them for ICE.

In June 2020, dozens of people urged county commissioners to end the program.

“If you choose to renew the 287(g) program, you’re choosing to spend taxpayer dollars, our dollars, to pay to hurt families, discriminate, and put many people’s lives on the line during this worldwide pandemic,” one opponent said.

Despite the opposition, commissioners voted 3-2 to renew the program — this time indefinitely.

Republican commissioners Glen Whitley, J.D. Johnson and Gary Fickes outvoted the two Democrats, Devan Allen and Roy Charles Brooks.

Critics of 287(g) say it’s not a good use of local law enforcement resources and leads to racial profiling.

A 2013 survey from the University of Illinois Chicago found that when law enforcement works with ICE, it makes many Latinos hesitant to report crimes.

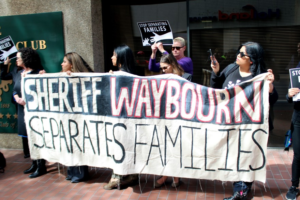

Anti-287(g) protesters stand outside a forum about the program hosted by the Fort Worth Hispanic Chamber of Commerce in 2018.

Christopher Connelly / KERA News

In Tarrant County, opponents of 287(g), like the group ICE Out of Tarrant, continue to organize against the program.

Activist Kassandra Dobbs spoke out at a commissioner’s meeting last month.

“I don’t know if anyone else sees the problem in having a program just forever be in place, but I do, Dobbs said. “I don’t think that that’s something that we should stand for.”

Opponents of the program later chanted, “Judge Glen Whitley, turned your back! Gary Fickes, turned your back! J.D. Johnson, turned your back! Fight’s not over, we’ll be back!”

The group got kicked out of the meeting. Whitley said he wanted them cited, if not barred from meetings entirely, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram reported.

What Is The 287(g) Program Supposed To Do?

Around the country, 146 local law enforcement agencies have some form of 287(g) agreement with ICE, including 26 in Texas. Joining is voluntary, and ICE has worked to expand the program in recent years.

Sheriff Bill Waybourn, Tarrant County’s chief jail administrator, signed up for the 287(g) agreement after he took office in 2017.

He told KERA in an interview last year that the program has identified undocumented people charged with serious crimes.

“If we don’t use our own discretion in order to hold them fully accountable, then we’re sending them back into the neighborhoods,” he said. “So if we have a responsibility to have safe neighborhoods, then law enforcement should cooperate together.”

Tarrant County Judge Glen Whitley has said if the program keeps a person in custody and prevents them from committing more crimes, it’s worth it.

“The folks that we’re holding onto in 287(g) are the bad apples,” he said.

“Bad apples” isn’t a label that should be thrown around lightly, said Albert Roberts, a criminal defense lawyer and former candidate for Tarrant County District Attorney.

“I definitely think it’s wrong for the county judge to use that term when he’s talking about folks who are sitting in our county jail, because the majority of the folks sitting in our county jail are just people accused of crimes,” Roberts said.

All it takes to get caught in 287(g) is a charge, not a conviction. That means even if someone’s criminal charges are dropped, they can still be still subject to 287(g)’s consequences, Roberts said.

Roberts works with undocumented clients. He said they face harsher penalties than U.S. citizens when they end up in jail.

Citizens charged with crimes can bail themselves out and go home to fight their cases.

Undocumented people often have to pay a lot more money to bond out, Roberts said, and then the 287(g) program could incarcerate them again.

This time, in ICE detention.

“If you want to see your community prosecuted, then fine. Just say that,” Roberts said. “Go on record and say, ‘You know what, I want to see undocumented folks prosecuted harder and harsher. I want them to pay more money. I want them to go through more trauma when they make a mistake.’ Because that’s what you’re doing.”

A Lack Of Information About The Program

Critics also have concerns about a lack of transparency related to 287(g).

A complete accounting of the program is hard to come by. In 2019, Tarrant County Commissioner Devan Allen, who opposes 287(g), said the sheriff wasn’t providing enough information about it.

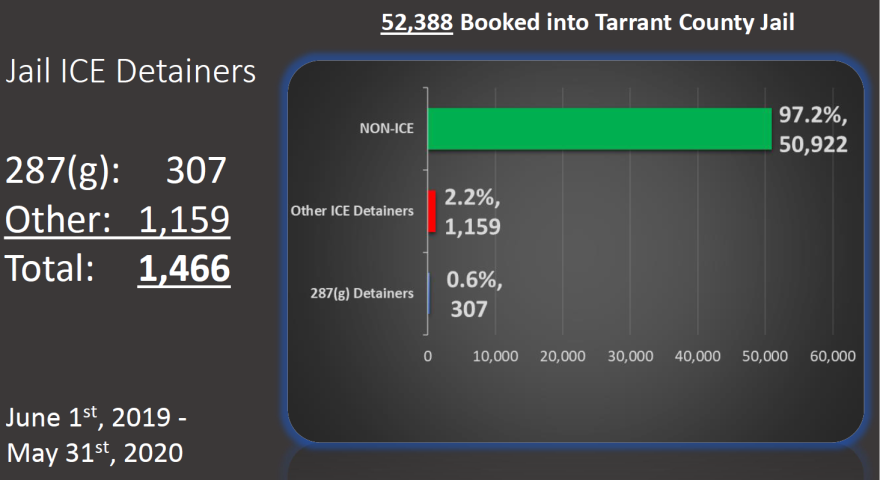

Last year, the sheriff’s office presented a chart of more detailed data about who has been flagged in the program.

Over a one year period, Tarrant County sheriff’s deputies flagged 307 people in the county jail as undocumented under the 287(g) program. Out of those 307 people, 70 were deported. There were over 1,100 held in county jail during that period under other ICE detainers.

Tarrant County Sheriff’s Office

From June 1, 2019 to May 31, 2020, sheriff’s deputies report they flagged 307 people under the 287(g) program. Those individuals were charged with felonies or certain misdemeanors. Deputies ignored the immigration status of people charged with the lowest level of misdemeanor.

Out of that group of 307:

- 236 went to ICE custody.

- 70 were deported.

- Another 61 people left the country voluntarily.

Since that presentation, KERA has learned that sheriff’s deputies have flagged at least 114 additional people in 287(g).

On a national level, ICE lacks full information about its 287(g) agreements.

In a January report, the federal, nonpartisan Government Accountability Office found that although ICE’s website lists examples of people who have been deported as a result of the program, the agency doesn’t have complete data.

“At the time of our review, ICE could not determine the total number of encounters through the 287(g) program that resulted in the detention or removal of the individual,” the report states.

The report also found that ICE doesn’t have concrete performance measures for ithe agreements.

“As a result, ICE is not well-positioned to determine the extent to which the program is achieving intended results,” it says.

Emily Farris is a political science professor at TCU who studies county sheriffs. She said instituting the program in Tarrant County was a political move on the sheriff’s part. Waybourn has aligned himself with former president Trump’s hardline stance on immigration.

“This isn’t a policy that’s being made or decided because of data or because of community input, but out of politics and Republican politics,” she said.

KERA reached out to each county commissioner seeking comment for this story. All either declined or did not respond.

The commissioners no longer have to vote to renew 287(g), but they did agree to an annual review of the program.

More than a year after the last vote, that review hasn’t come up in commissioner’s court.

Got a tip? Email Miranda Suarez at msuarez@kera.org. You can follow Miranda on Twitter @MirandaRSuarez.