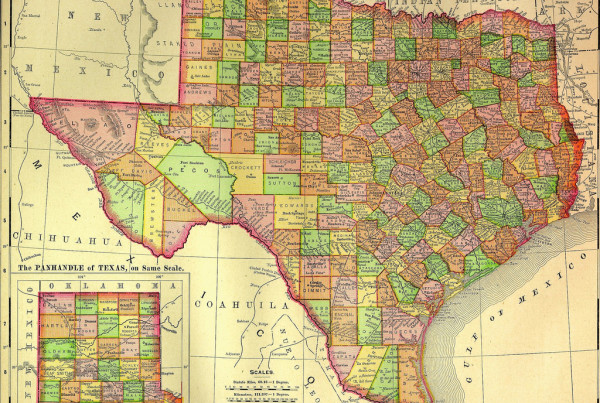

Paulino Serda was a small ranch owner near Edinburg, Texas, in 1915 when a group of Mexican bandits came through town. They demanded he open the gates that connected the ranches so the group could pass.

“And of course, you didn’t really say ‘no’ to these individuals,” says Serda’s great-grandson Trinidad Gonzales, assistant chair of history and philosophy at South Texas College. “And apparently word got back to the Rangers that this had occurred. And when they went to his ranch, they asked to talk to him, to question him in private. And while that was going on, my great-grandmother heard the gunshots.”

The Texas Rangers killed Serda, no questions asked. Gonzales’s family was one of many affected by some of the worst state-sanctioned violence in the history of the U.S. Today, he’s part of a group of scholars working to get this part of Texas history recognized.

“Well essentially, the Matanza resulted because of reprisals by state and local authorities against a guerrilla uprising that had occurred,” says John Morán González (no relation), associate professor of English at the University of Texas at Austin and part of the group of scholars.

He says the guerrilla uprising was small and not very well organized, made up of bandits or Mexican revolutionaries. Nevertheless, the Texas Rangers were called in to control the situation. The repression, however, was not just directed at the bandits, but at the Texas-Mexican population as a whole. Morán González says that between 1915 and 1919, hundreds – if not thousands – of Mexicans and Tejanos in South Texas were killed by the Rangers and other vigilantes.

“So in that sense, the project of policing throughout much of this era was also about the establishment of a racial order, of white supremacy,” Morán González says.

For the first time, this part of history will be acknowledged by the state of Texas through an exhibit at the Bob Bullock Museum called “Life and Death on the Border, 1910 to 1920.”

“The scholars and professors approached the Bullock with this idea of this exhibit, to learn about this piece of history,” says Jennifer Cobb, Associate Curator of Exhibitions at the museum. “I never knew about it until I started working on this exhibit, and it was astounding that this is not public knowledge. This is largely faded from public memory after the period ended, aside from those who were directly affected by it.”

Cobb says the exhibit will be a look into what life was like leading up to, during, and after this violent period. It’ll showcase court documents, photographs and artifacts from the era, even one of Pancho Villa’s saddles. But Gonzales, whose great-grandfather was killed, says the exhibit is more than just about the victims.

“It’s also a way of celebrating our resiliency of the community against these conditions,” Gonzales says. “To respond by pursuing our civil rights and our rights as equal participants within our society.”

This violent period spurred what would become the Mexican-American civil rights movement. One important document on display is the complete transcript of the 1919 Texas Legislative Investigation that looked into the Texas Rangers’ actions, and found them guilty.

“This was the first time that the Texas Rangers had ever been called to be held accountable for atrocities against the Texas-Mexican community by the legislature,” Morán González says. “Prior to that, the Texas Rangers knew pretty much anything goes.”

The group of scholars – which includes both Gonzales and Morán González – have named their project Refusing to Forget. Their goal is to commemorate this forgotten period of Texas history by making it known to a wider public. Currently, it’s not part of the Texas public school curriculum. The exhibit is just one part of their efforts: They are also working to erect historical landmarks and develop a traveling exhibit to tour Texas, and eventually, the country.

The Bullock exhibit will open to the public on Saturday, and run through April.