From Texas Public Radio:

The signs of past abuse on Britney Pollack are unmistakable.

“I always get judged for my arms,” she said.

The 18-year-old’s left arm is covered in scar tissue from hundreds of self-inflicted cuts.

“For me, people didn’t want to keep me — didn’t want to have anything to do with me because I look like I’m insane. But in all reality, we’re not insane. We’re just looking for somebody to love us,” she said.

The cutting helped her cope with past trauma from an abusive family, she said, and with being in Texas’ foster care system the past four years.

Since she was 14, Pollack described her time in the system as being shuttled between treatment centers and psychiatric hospitals. Often changing doctors and medications each time — never finding stability.

Now, more than a dozen placements and 230 different medications later, she said the state’s child welfare system is a lie.

“I feel like it’s a lie because they say they’re trying to protect us. They want to keep us safe. They want to make sure we’re being taken care of. But we’re not,” she said.

Her cycle often led to having no place and being labeled a “Child Without Placement” or CWOP.

That means being warehoused in taxpayer funded hotel rooms with other kids. At one point in 2021, there were more than 400 children a night.

Pollack spent months in them. Months eating fast food or a sandwich for each meal (she can’t eat sandwiches anymore), being squeezed into a two-bed room with three or four case workers paid to watch them.

While at the hotel, the state often offered no psychiatric treatment or other services.

And after some hotels started throwing foster children out over their behavior — state staff cracked down even more.

“It got to the point where we couldn’t go nowhere,” she said. “We had to stay in our hotel room and not move. We were like locked in there. A CPS worker would sit at the door. We couldn’t get out because technically we are putting our hands on somebody and we end up in jail.”

Children without placement hotels exist because Texas doesn’t have enough places for children like Pollack — ones with high mental health needs — to go.

Federal court monitors call these placements dangerous, noting in its reports times when kids got assaulted, ran away or were sex trafficked.

And for more than three years, what was supposed to be a temporary placement for kids has often lasted for weeks or months. The state showed it cut the numbers in CWOP in half — but it’s still more than 100 kids a month.

It cost more than $260 million over three years.

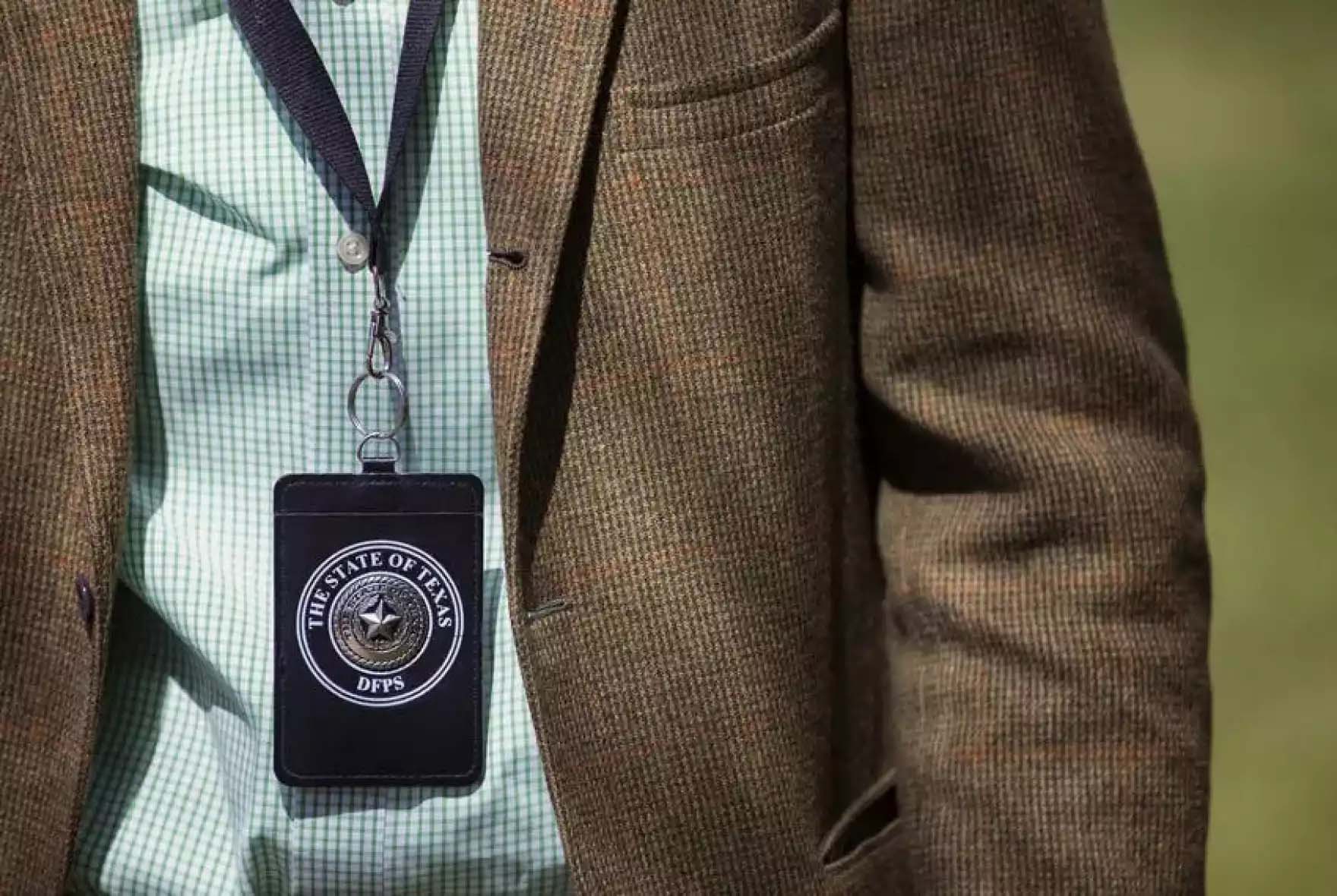

Texas’ foster care — run by the Department of Family and Protective Services and the Health and Human Services Commission is among the most troubled in the nation, and Texas regularly ranks towards the bottom of child well being.

For more than a decade, the state has faced federal action over what a Judge called a “broken” foster care system.

A federal court is now weighing whether to impose hefty fines over the state’s inability to make progress on court-ordered reforms.

“There’s just so much waste,” said Paul Yetter, an attorney representing current and former foster youth in the ongoing federal lawsuit against Texas’ system.

“There is no coherent plan to fix the problem. The state is just dumping buckets of money on a shadow system that is hurting children,” he said.

Yetter said this shadow system is a good example of how Texas has failed to reform.

Texas is a big state and state officials can’t just snap their fingers and fix it. But he said — for much of the last 13 years — it wasn’t trying.

“It has instead been aggressively refusing and opposing reform. So we have a big system with lots of problems, and we have a leadership that is just not willing to work cooperatively to get it fixed or to find solutions,” he said.

Yetter pointed to a hearing just last week showing the state’s uncooperative attitude.

Judge Janis Jack — who called the system broken when she ruled against the state years ago — has been overseeing the implementation of her orders ever since. The Clinton-appointed judge has a no-nonsense reputation and doesn’t shy away from grilling state executives.

A week before the hearing, Jack ordered the state to bring documents showing what if any effort the state had put into executing on recommendations an expert panel made to end CWOP from years ago.

At the time the panel, made up of child welfare experts some of whom had run other state’s systems, said they were shocked at the kinds of numbers they were seeing without placement in Texas. Their recommendations were not binding.

Within minutes of beginning the hearing, it became clear the state had not delivered the court-ordered documents.

“It’s after 9. Where are the documents? I need the documents in hand right now,” Jack said.

The state’s attorneys did not have them.

Judge Jack threatened contempt.

”Commissioner Muth, Commissioner Young,” she said, addressing the heads of the Department of Family and Protective Services and the Health and Human Services Commision, ”have you ever seen the inside of a jail cell?”

Ultimately, she agreed to give the state more time — two more days. But later in the hearing, her frustration boiled over. Judge Jack calls the bureaucracy that produced these ongoing failures “horrible.”

“You know what year this is? This is 2024. How long have we been wrestling with this problem?”

Conservatives like Texas State Rep. James Frank allege the lawsuit itself causes some of the problems it’s railing against.

“The judge is the arsonist saying there’s a fire,” Frank said.

He, like many others in his party, believe the federal lawsuit wastes money and resources. The Dallas Morning News recently reported the state had spent $180 million on the foster litigation. He said it’s scaring away scarce treatment providers that could care for these kids.

“Basically nobody wants to work with the state of Texas on high risk kids, because you are going to end up under the thumb of the judge if you do,” he said.

Texas has argued its foster system has shown significant progress on many of the court’s orders and is substantially in compliance.

In the coming weeks, Jack will decide if they actually are — potentially levying hefty contempt fines.

The system is still clearly in crisis, said Christie Carrington — a retired DFPS worker who now works for the state employees union.

“It’s not safe for anybody,” she said, referring to CWOP.

Safety around CWOP is one of the reasons people are fleeing the department. One in four case workers leave within a year of being hired. While only a fraction of the more than 25,000 Texas kids in foster care are in CWOP — Carrington testified at an earlier hearing that CWOP had hijacked the department.

“Keeping children safe is our job. That’s the only reason we exist. And if we’re not doing that, then we might as well pack up and go home,” she said.

She said the lack of progress is astounding, and she asked, if state leaders can spend billions erecting barriers on Texas’ southern border, why can’t they can’t fix this?

“The governor can do it. He does everything else, you know, razor wire in the rivers. What about these children?” she asked.

Texas is not the only state to deal with legal fights over foster care. Alabama, Mississippi, Kansas, and a host of others have all dealt with federal oversight — many still are.

18-year-old Britney Pollack’s time in Texas foster care went straight from a CWOP hotel … to county jail.

Like many kids with high needs in the program, she broke the rules — and a worker said Pollack hurt her when she tried to take away the girl’s phone. Pollack denied she ever touched the worker but she spent two weeks in the Brazoria County Jail for a misdemeanor.

She said her time with Child Protective Services was so bad that she would have rather stayed with her abusive family.

“Because we didn’t ask to be in CPS. I didn’t ask CPS to take me away from an abusive family,” she said. “All we want is a family. And when we’re not getting that, it hurts.”

Now living in a private group home, Pollack is free of the department. Tattooed over the hundreds of cutting scars on her left arm in dark cursive black lettering is the word “Survivor.”