This story originally appeared on KUT News.

How does the waiver, and the money attached, help Texans?

Our explanation starts at Seton’s UMC Brackenridge hospital in Austin. Nurse practitioner Ana Marie Houser walks into a patient’s room, where the lights are off. Some sun is shining in. Houser greets her patient, who has a life-threatening illness. Family members are in the room, including her patient’s mother.

“Do you have any concerns about all of the information that you’ve received?” Houser asks in Spanish. “I know that many doctors come in here, one after the other. Do you have any questions?”

Houser offers support, purposely sits down on a stool so she can see her patient at eye level. How’s the nausea?, she Houser asks. Does everyone in the family know how serious her condition is? Do they need her help in reaching out to family?

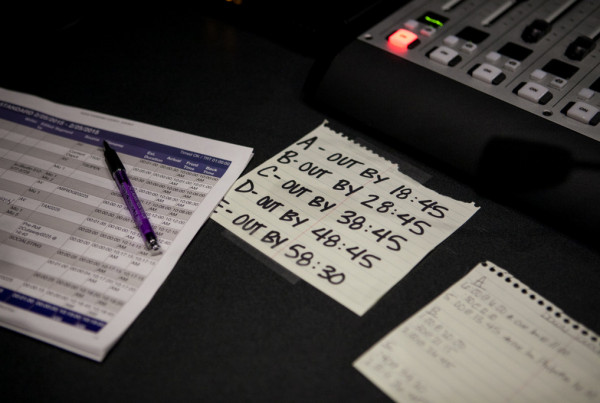

As patients journey ‘from point A to B’

“It really helps create a model of shared decision-making,” says Steven Bekanich, a palliative medicine physician with Seton. His patients are coping with side effects from illnesses or trauma that could last a while, so Bekanich and his team help them through means other than just medication. His says palliative care is not hospice care. His team includes a social worker and a chaplain to allow for culture, spirituality and family history to play into the care.

“In palliative medicine we say, ‘hey, as they journey from point A to B, we want them to feel as well as possible,'” Bekanich explains. “That’s the goal. I don’t know if they’re going to get to point B, C or D. But I know that I can help them, with our skill set, get there in a more dignified, comfortable manner.”

Palliative care doesn’t bring in big bucks for a hospital, though, and insurers don’t usually pay for it. The type of care Bekanich gives is largely made possible by the Medicaid 1115 waiver money.

That waiver uses about $2 billion in local tax dollars from across Texas to draw down about $4 billion a year in federal matching dollars. This money pays for uncompensated care provided by safety-net hospitals, and also some 1,500 delivery system reform projects statewide, like the palliative care.

Now, Texas has to reapply for the money this fall, before the five-year agreement expires next September.

Moving forward, without Medicaid expansion

“I think naturally the folks that are earning these funds now are concerned about what happens after the five years,” says Lisa Kirsch with the Texas Health and Human Services Commission, the state body negotiating the new waiver.

The waiver expires in September 2016. In the meantime, remember that the Affordable Care Act wanted states to expand who qualifies for Medicaid. The Supreme Court ruled to make that optional, and Texas has chosen not to do it. But the feds are not planning to pay for care to uninsured Texans that would have been covered by Medicaid.

State Rep. Sylvester Turner, a Houston Democrat, raised his concerns about the prospects of a new waiver at a hearing in May at the State Capitol.

“The reality is, is that our hospitals — urban, rural, general, you name it — are at risk if we do not address the fact that the uncompensated care portion of the waiver is about to come to an end,” Rep. Turner said.

He pointed out the not-so-smooth negotiations between federal Medicaid officials and another state.

What’s happening in Florida?

“They sent a signal to Texas to say please look at what’s happening in Florida,” Turner said.

What did happen in Florida? Its waiver was renewed, but that state’s getting less money this time around, and like Texas, Florida didn’t expand Medicaid.

The feds could say to Texas, ‘if you refuse to expand Medicaid eligibility, then you’ll need to increase Medicaid reimbursement rates.’

“So that every time a patient goes to the hospital or goes to the doctor, we’re paying closer to cost than what we’re paying now,” Lisa Kirsch with the Texas Health and Human Services Commission says.

But she says she’s confident Washington will work with Texas. After all, Texas now has the highest rate and the highest number of uninsured.

Plus, it has patients like the one in Austin, getting support from the palliative care team to make very difficult life decisions.