From KERA:

This story is the third in a five-part series “The Asylum Trap: Stories From Migrants Forced To Wait In Mexico While Seeking Asylum.”

Steering carefully, Will Rocci maneuvered a van across a bridge from El Paso, Texas, into Ciudad Juárez, Mexico.

“We’ve got a list of families today who have reached out to us asking for dispensas,” he said, nodding toward a clipboard with the day’s mapped out route.

He makes these deliveries a few times a week, to asylum seekers living outside of shelters.

“Some of them have children,” Rocci said. “Some are just single adults who have lost their jobs. Just a lot of people battling right now due to the pandemic and not having a source of income to support themselves.”

The van’s back seats are removed, making room for supplies Rocci and his colleague Lindy Morrison will pick up and deliver: eggs, beans, baby formula.

Will Rocci drives through downtown Ciudad Ju‡rez en route to take Levis to a Dental Appointment on September 24, 2020. Rocci, along with Lindy Morrison, run Seguimos Adelante, an NGO that has continued helping migrants stuck in Juarez because of MPP, despite the pandemic.

Paul Ratje for KERA

“We’re also picking someone up for a dentist appointment this morning,” Morrison added.

Once over the bridge, Rocci headed to a dusty neighborhood on the outskirts of Juárez. He pulled up a steep hill and parked in front of a small, cinder block house, with children playing out front.

“They contacted us a few days ago saying they pretty much have no food and also asking for some diapers,” Rocci explained.

‘They have basically closed the door on us’

A woman came out in a striped shirt and surgical mask, her long, dark hair in a high ponytail. She said her family recently started renting this house and that they’re generally comfortable here; they get along well with the landlord.

After fleeing persecution in Honduras, she said her family has been living in Juárez for more than a year. KERA is not to use her name, since her asylum case is still pending.

“We left because we can’t live in our country anymore,” she said. “For the safety of our family. At the moment we leave to seek refuge, they have basically closed the door on us.”

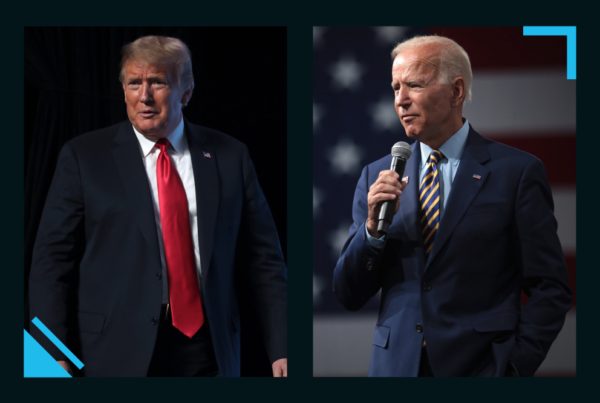

There are currently thousands of asylum seekers like her in Mexico. Under the Trump administration’s “Remain in Mexico” policy, they’re forced to wait in an unfamiliar country for their day in U.S. immigration court.

The policy, formally known as the Migrant Protection Protocols, or MPP, has been controversial since it began in 2019. The U.S. Supreme Court recently agreed to hear a case concerning MPP.

Will Rocci is pictured inside a group home in Pan de Vida Migrant Shelter in Ciudad Juárez on September 24, 2020.

Paul Ratje for KERA

Now, with courts paused because of COVID-19, there’s no timeline for when those in MPP will be able to resume the asylum process. The Trump administration has also been accused of using the pandemic to ‘end asylum as we know it.’

Getting by…until COVID

Before the pandemic, Rocci and Morrison probably wouldn’t have met the first woman on their delivery route. They mostly worked in the network of migrant shelters that popped up in Juárez out of necessity, after the Trump administration began sending asylum seekers back across the border to wait out their legal proceedings. They formed a small nonprofit, Seguimos Adelante, to provide on-the-ground support.

They thought they reached a lot of people through that work.

Then the COVID-19 pandemic struck.

“We suddenly discovered hundreds if not thousands – I mean so, so many people living outside of the shelters that we were unaware of,” Morrison said.

Many of those asylum seekers had more or less been getting by before the pandemic. Some received money from relatives in the U.S. Some found low-wage jobs, like in the city’s maquiladoras, or factories. They rented out shared rooms or apartments or lived long-term in hotels.

The Honduran woman said her husband had steady work in construction. But those jobs have dried up. Now, she told KERA, covering rent and basic necessities is a real challenge.

“There’s a lot that we don’t have because of the economic situation, because of the lack of work,” she said. “When you work, you have the possibility of sustaining yourself. But without work it’s really hard.”

Lindy Morrison and Will Rocci make a food delivery to Cubans in Ciudad Juárez on September 24, 2020 at dusk.

Paul Ratje for KERA

A makeshift lifeline

Rocci gets messages from families like hers nearly every day now, he said, “saying hey, we’re out of work, can you help us? Hey, we’re running low on food, can you guys help us out?”

Now, he and Morrison provide a makeshift lifeline for these families.

Morrison played with the woman’s three children while Rocci swung the van doors open, revealing what looked like a scaled down grocery store: egg cartons stacked high; plastic bins filled with garlic, potatoes and onions. He went through the items, one by one, asking the woman if she would like some: Toothpaste? Avocado? Canned tuna?

The woman said yes to everything. She brought out a small bowl to collect tomatoes. Rocci scooped black beans out of a large sack and poured them into a plastic bag.

The supplies should last at least a week, tiding the family over as they continue to wait for court to reopen.

And for now, they received a bit of bright news: after months without work, her husband was called in for a construction job.

“We don’t know if it’s for a month, for a week,” the woman said. “But at least for today he’s working.”

After a couple more stops, Rocci parked the van on a leafy street in downtown Juárez. A man in a soft gray shirt and baseball cap came out of the apartment he shares with several other Cuban asylum seekers. He loaded up on rice, onions and olive oil for the group.

The man also asked KERA not to use his name because his asylum case is still open. He said pre-COVID, he too had an okay job in Juárez, separating plastic at a recycling center.

Then everyone was sent home. He said he hasn’t worked in months now and ended up having to sell his clothes to earn money.

“A lot of people are just feeling very desperate,” Morrison said.

Will Rocci delivers food to Cubans in Ciudad Juárez on September 24, 2020. Many migrants in MPP found themselves out of work during the onset of the pandemic, which is why Seguimos Adelante has been offering food assistance throughout the pandemic.

Paul Ratje for KERA

Hanging hopes on the presidential election

In the past, no matter how dire their situations became, asylum seekers had their next court dates to cling to.

“Any time you meet someone, they know what that date is,” Morrison said. “Their kids know what that date is. Now, there’s not really anything concrete in that same way.”

“I think a lot of people have heard that, depending on how the election turns out, potentially MPP could be ended,” Rocci said. “So I think that’s the biggest hope that a lot of people are holding onto right now.”

Like the Cuban asylum seeker, who took a break from stocking up on supplies to talk U.S. politics.

“Our hope is that Biden wins,” he said. “That he wins and fulfills his promise. Then we’ll see if we’re able to cross.”

Biden, the Democratic candidate, has promised to end MPP during his first 100 days in office.

Asked what he will do if Trump is re-elected, the man paused and cleared his throat.

“I’ll be straight with you,” he said. “The idea is to get to the United States, one way or another. There might come a day when I decide to try to cross illegally, because there’s no other way and because I’m not gonna stay here.”

He said the current situation is not sustainable for anyone.

Mallory Falk is a corps member with Report For America, a national service program that places journalists into local newsrooms. Got a tip? Email Mallory at Mfalk@kera.org. You can follow Mallory on Twitter @MalloryFalk.