From KERA:

It’s a Monday morning, and someone’s getting ready to cook a batch of the illegal drug PCP near the University of North Texas in Denton.

I’m riding in the backseat of a Ford Fusion with Guido Verbeck, a forensic scientist and professor at UNT, to an empty trailer home that looks abandoned.

That’s where “the cook,” as they call it, is about to go down.

Verbeck doesn’t work in law enforcement, though he does look the part, with a clean shaven head and rugged cowboy boots.

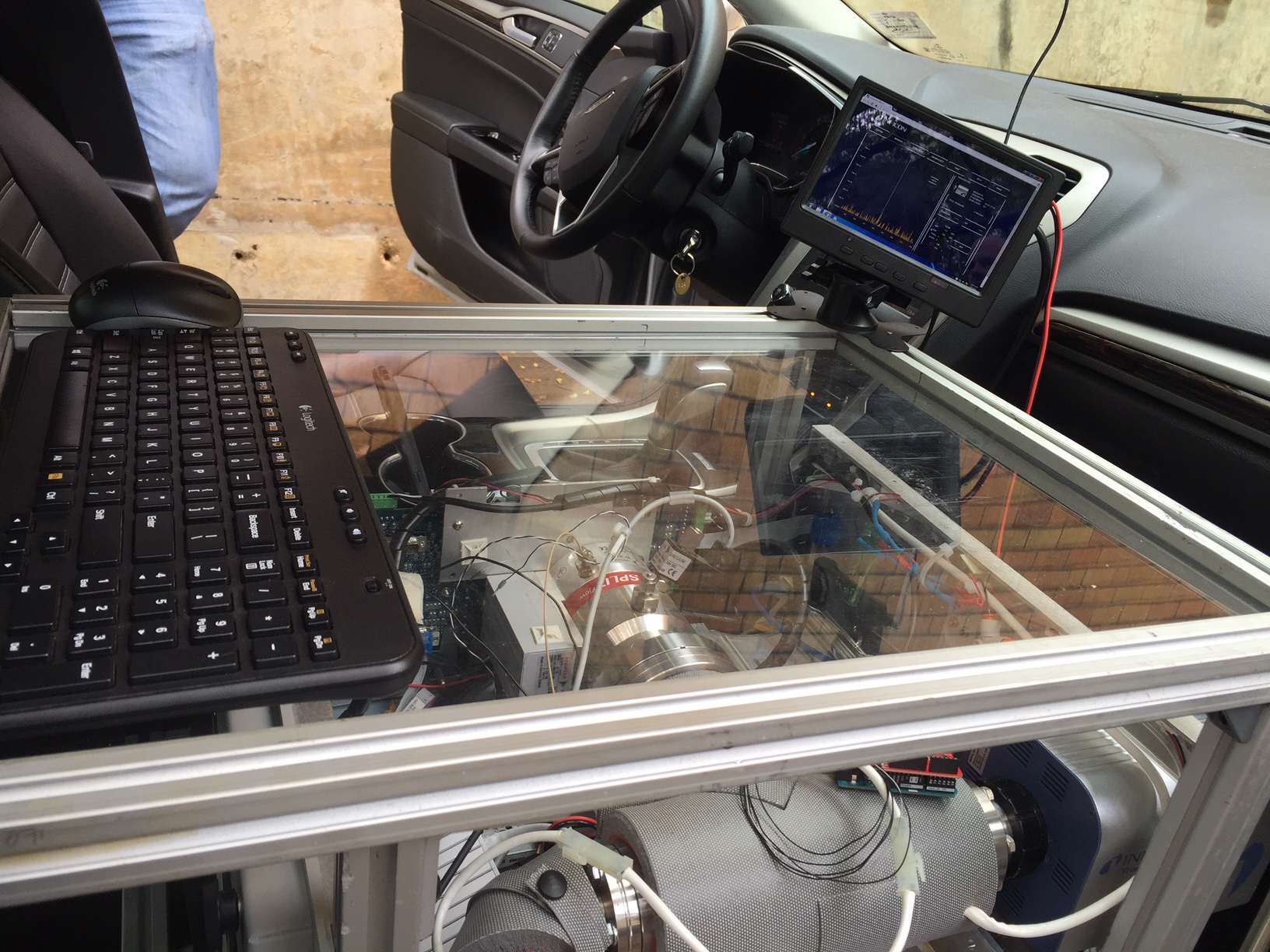

We’re here to test out a drug detection device Verbeck created. It’s a big black metal machine sitting where the front seat should be.

The official name? A mobile mass spectrometer. But it’s basically a drug sniffer.

“The truth of the matter with this car is it’s like a dog,” Verbeck says. “The chemistry has to go into the nose.”

‘Drug dealers are some of the best capitalists’

Two hidden pipes are pulling in air from outside – one is by the rear view mirror and another is down where the fog light is. The pipes feed the air to the device’s nose, so to speak. It’s a tool scientists use to measure the mass of different molecules. The mass can reveal the identity of the molecule. For example, carbon is 12 atomic mass units. For meth, it’s 149.

Here’s the thing, though: the device isn’t exactly searching for meth or PCP. It’s searching for the chemicals used to make those drugs — the ingredients.

“It’s looking for pyridine, piperidine, all of the chemicals that would be required to making the process,” Verbeck says. “Most of the time, we say that the drug dealers are some of the best capitalists. Once the drug is made, it’s on the street. You’re not going to waste any time on the product. So what you really need to do is train these labs to look for the precursor items to know that type of activity is going on because the drug’s probably not there.”

Inside the trailer house, UNT Ph.D. candidate Ethan McBride is pulling out his ingredients. He’s placing glass beakers on the grimy bathroom sink and a hot plate on the toilet tank.

“This is the precursor to PCP, to angel dust,” McBride says. “It’s incredibly easy to make.”

McBride says this is a typical setup for a clandestine drug cook.

“I think it’s important to be able to put yourself into the mind of the clandestine chemists,” he says. “Generally, these are not classically trained chemists, but they’re very good at what they do. I do think they come up with very creative solutions sometimes and we have to be equally creative to catch them.”

Monitoring the ‘heart rate’ of chemicals

While the hydrochloric acid and piperidine spin in the beaker on the hot plate, Guido Verbeck is circling around in the car, watching a graph on a digital screen that looks like a GPS display.

That’s where we’ll see signs of the chemicals seeping out the front door and bathroom window. Sure enough, as soon as we circle around the back of the trailer and the air enters the sniffing device, a few digital peaks and valleys pop up on the screen.

It’s like we’re monitoring the heart rate of the chemicals in the air.

“You can see the heavier peaks will get more intense as we get into that [air] stream and as we drive away it’s going to start getting lower,” Verbeck says.

Verbeck has already partnered with the Denton County Sheriff’s department and is talking with federal law enforcement about using the device. He hopes to make the graph easier to read so first responders who aren’t trained in forensic science can clearly see if there are dangerous chemicals in the air, or if someone’s cooking illegal drugs.

And get this: Verbeck even imagines putting the device in a self-driving car – with no officer inside.

“Where a person doesn’t have to put themselves in danger,” he says.

Empowering police vs. protecting privacy

Sniffing out illegal activity from a drive-by could be a great tool for police, but Eric Sterling says the technology walks a fine line between empowering law enforcement and protecting privacy. Sterling is executive director of the Criminal Justice Policy Center in Silver Spring, Maryland.

“What we think of as notions of privacy that you can do various activities, outside the public eye and get away with it, those ideas are being demolished both by technology and by law,” Sterling says.

Sterling doubts that a map showing chemicals concentrated around a house would be enough to get a search warrant, but he says a judge might give the go-ahead if there were other clues.

“You’d want to have surveillance that perhaps might show unusual kinds of pedestrian traffic for the location, run checks on the vehicles that run in and out and find out if they’re criminal records,” he says.

Besides sniffing out criminals, there are less controversial uses for the device. Sterling and Verbeck say it’s possible environmental cleanup crews, even firefighters, could use it to identify chemicals in the air from a safe distance.