Vallerie Stephanie Lamour, 36, said the racism in Panama was so bad, that she was once told she “smelled ugly and Black.” She moved there from Haiti in 2005 after a violent attack at her school, where she saw her cousin get shot in the eye.

Lamour, in Spanish, said for 15 years she tried to make a life for herself, but she struggled to get immigration papers, find work, get out of poverty.

“I couldn’t stay in Panama,” said Lamour, who was abandoned by an ex-boyfriend when she got pregnant with her twin sons. “I couldn’t find help and my children were growing up.”

At a new short-term migrant shelter in Houston, Lamour explained that she finally got a work permit in 2020 — but the pandemic dashed any hopes of finding work to help support her four children. So she and her boyfriend made a decision: come to the United States.

Their plan almost worked.

Last week, she said, they crossed from Mexico into Del Rio, Texas. Border officials apprehended her, her boyfriend and her two 7-year-old twin sons and separated them. Her boyfriend — also from Haiti — was taken to a detention center. Lamour and her sons were let go.

Tears streaming down her face, Lamour explained that without her boyfriend she has nowhere to go. They were headed to New Jersey, where her boyfriend has family, but she said that family won’t accept her without her boyfriend there, too.

“The truth is I don’t know what I’m going to do,” Lamour said. “I never thought I would be in a situation like this, separated from the person that I love.”

Many adults who cross into Texas from Mexico are being detained and deported, like Lamour’s boyfriend, but some families are being released into the U.S. by immigration officials and will face their immigration cases in court several years down the road.

And they’re not all from Central America.

Thousands of Haitian migrants are making their way to the United States, many coming after first living in other countries.

Migration statistics from Panama’s southern border show that more unauthorized Haitians have crossed than any other nationality in 2021 — some 8,600 people through the month of May. Another 1,500 migrants were children of Haitians born in Chile and Brazil.

In the last month, Doctors Without Borders deployed medical and mental health services at the southern border of Panama due to the surge in migrants there, especially people from Haiti, where people are facing sexual assault, robberies, drownings and dehydration.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection doesn’t have a recent count of Haitian migrants crossing, but Jessica Bolter, with the Migration Policy Institute, said numbers from Panama are a good proxy for what we’re seeing at the U.S.-Mexico border.

“There’s definitely a lot of factors that are combining to lead to this increased flow of Haitians at the moment,” said Bolter, who studies African and Haitian migration in the Americas.

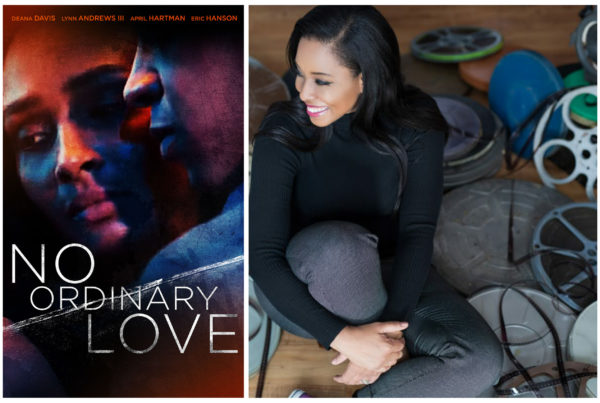

At the new family transfer center in north Houston, Haitian migrant Jouseline Metayer sits with her 7-month-old son, Jayden.

Elizabeth Trovall / Houston Public Media

“Haitian immigrants and African immigrants as well really do tend to experience systemic racism and discrimination, making it more difficult for them to get hired for jobs, to access housing, to get education,” said Bolter.

They also face language and work authorization barriers. She said in Chile, a country that opened its doors to many Haitians after the 2010 earthquake, visas are closely tied to having a job offer.

“It’s been really difficult for Haitian immigrants to find jobs in Chile,” Bolter said. “Some of this is due to the language barriers, some of this is because a lot have ended up falling into irregular status and so once they’re in irregular status it’s hard to get someone to offer them a job.”

During the pandemic, country conditions have worsened in both Haiti and Latin America, and Haitian migrants see the U.S. economy as a beacon of hope post-pandemic, Bolter said.

“As the U.S. economy is now starting to open back up and recover much more quickly than the economies in places like Brazil or Chile, that’s definitely an attractive factor for the migrants as well,” Bolter said.

At the Houston shelter, Jouseline Metayer from Haiti sat with her 7-month-old son, who was born in Chile. She had immigrated there, but struggled to find work. She crossed South America on foot and by bus to get to the U.S. with her son and boyfriend, who was also detained and separated from them.

She said on the journey she would see other women getting raped. They would walk by dead bodies in the jungle.

“Every time I saw a dead person, I said ‘I’m not going to die like that with my baby’,” she said in Spanish.

They survived, but now without her boyfriend to help support their family, her future is uncertain.

While both Metayer and Lamour figure out where to stay next, like many Haitian families they also have pending immigration cases, which may take years to wind through the courts.