From KUT:

Mark Escott’s role as interim public health authority of Austin-Travis County was meant to be a quick, six-month stint.

When he was hired in October 2019, he joked with Stephanie Hayden-Howard, Austin Public Health’s director at the time, that some disaster or other was bound to crop up during his brief tenure; he had previously served in a similar role in Montgomery County, and in that position was dealt a hand that included an Ebola scare and a severe flu season.

“I warned her that something was going to happen. I just wasn’t sure what it was,” Escott said. “[Then] right out of the gate, we had the first case of measles in 20 years, the first case of German measles in 20 years, and then, of course, the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Escott’s six months as health authority turned into 20 as he became the face of Austin’s pandemic response. On March 13, 2020, it was Escott who announced the first local cases of COVID-19. He continued to share vital updates on the virus, guiding the public through the lockdown and urging caution as case counts reached multiple peaks.

Behind the scenes, Escott learned both how local and national public health systems excelled and came up short. Dated public health infrastructure, for instance, was a major pain point, especially early on.

“We were relying on fax machines to receive reports of COVID-19 cases,” he said. “I was manually inputting data into spreadsheets to share publicly and share with the City Council and Commissioners Court.”

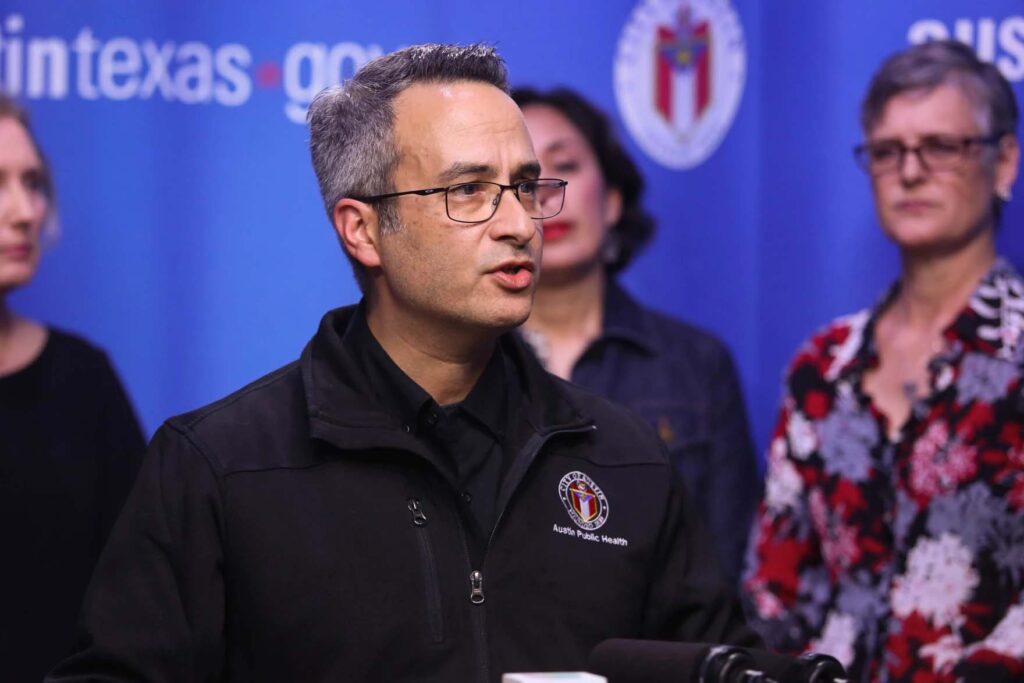

Dr. Mark Escott, interim medical director of Austin Public Health, speaks during a news conference announcing SXSW’s cancellation because of COVID-19, on March 6, 2020.

Julia Reihs / KUT

Now, three years after COVID-19 made itself known in Austin, Escott has settled into a new role as the city’s chief medical officer after passing the health authority baton off to Dr. Desmar Walkes. And while the pandemic is not over, Escott said that from a public health perspective, “the sting is starting to fade.”

He is focused now on using the lessons he learned from this pandemic to be ready for what comes next.

Escott is joining other local pandemic leaders as a principal investigator at UT Austin’s new Center for Pandemic Decision Science (CPDS). The center is directed by Lauren Ancel Meyers, a professor of integrative biology, statistics and data sciences who has led UT’s COVID-19 Modeling Consortium since March 2020.

According to Meyers, it’s a matter of when, and not if, the next pandemic arrives.

“There’s lots of pathogens out there that threaten us,” she said. “Global climate change means that they are spreading in different parts of the globe. Global connectivity means that it’s very hard to contain new threats at their source, and human encroachment on wildlands means there’s more opportunity for diseases to spill over into human populations.”

So, what can we do to be ready for that next pathogen? That’s what Meyers, Escott and more than 40 other multidisciplinary experts from across the globe hope to determine.

Austin’s playbook

With the help of a $1 million grant from the National Science Foundation, CPDS grew out of Meyers’ work leading the COVID-19 Modeling Consortium, which uses data to track the spread of COVID locally and nationally.

Like Escott, Meyers saw the timing of COVID’s arrival coincide uncannily with her work at the time; she was in the process of building a model for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that would show the pattern of how a pandemic might spread through the United States.

Lauren Ancel Meyers, a professor of integrative biology, has led UT’s COVID-19 Modeling Consortium since March 2020. She now directs the new Center for Pandemic Decision Science.

Michael Minasi / KUT

Meyers’ lab was quickly inundated with requests from everyone from Austin Public Health to the U.S. government.

Leading strategies to deal with future pandemics could come from Austin’s own playbook, including Meyers’ forecasting models and Austin Public Health’s staged alert system, which ranked community risk from COVID at levels from Stage 1 to Stage 5, with each stage bearing a specific set of behavior recommendations, such as masking and avoiding crowds. According to Meyers, this local system was among the most advanced and effective in the country.

“One of our projects is to go back and look at the alert systems that were put in place all over the world,” she said, “figure out which ones were effective and which ones were not, and start to put the building blocks in place for how we can very rapidly deploy staged alert systems as new and unexpected threats emerge.”

Grand challenges

Current pilot projects out of CPDS focus on what Meyers calls three “grand challenges”: anticipating new pathogens, anticipating and influencing human behavior, and integrating science into pandemic decision-making, including government policy.

To tackle that third challenge, CPDS has brought in collaborators with experience in designing war games for NATO and the U.S. Navy. They’re creating preparedness exercises, games that groups of city and state leaders can play to help “pressure test” their pandemic data systems and command-control structures.

The challenge of understanding human behavior will require a multidisciplinary approach. Meyers said this is an area where her work from the Modeling Consortium could still be advanced through the use of data that tracks people’s movement through their cellphones to identify areas of probable spread. To that end, computational scientists will participate in a CPDS “hackathon,” where they compete to build predictive models with mobility data.

“During the pandemic, we used that data to estimate how fast the pandemic or the disease was spreading today in a city, and then that would help us to predict how many people would end up in the hospital a week or two from now,” Meyers said. “But what we really want to do is take that data and gain a deep and more scientific understanding about how people move around on a daily basis in a city or even in a neighborhood.”

CPDS is also looking at human decision-making, such as the choice of whether to wear a mask or get vaccinated. That also includes how people respond to misinformation.

Escott said misinformation is inevitable in a pandemic scenario; it was even predicted back in 2001 during a pandemic wargame exercise the U.S. government and Johns Hopkins University ran called “Dark Winter.” Because of this, he said, incorporating the social sciences with data to better understand decision-making and communication is key.

“That doesn’t mean we’re going to create a system that’s going to rid ourselves of misinformation and contradicting views,” he said. “I think those contradicting views are certainly important to help feed decision-making and make better decisions. But ultimately, if we are all thinking about the pandemic response in the same way, and we understand what predictive modeling does and doesn’t do, it helps us have a more cohesive response and hopefully save lives.”

Ground zero

Having these projects based out of the CPDS in Austin is an important opportunity, Meyers said, because Texas is vulnerable to pandemic threats.

With multiple cities that serve as international hubs for travel, a large shared border with a foreign country and climates that support subtropical diseases, the state has often been on the front lines of battles with new pathogens. It was one of the first states to import an H1N1 case from Mexico in 2009, one of the few states with an importation of an Ebola case during West Africa’s 2016 epidemic and remains one of a handful of Southern U.S. states with mosquitos capable of spreading Zika.

“Texas is often sort of ground zero for the first or early importations of new diseases in the United States,” Meyers said, “so we have to be especially prepared locally as we hear about new threats emerging in other parts of the globe.”