Casting a ballot takes just a few seconds. You fill in a bubble on a sheet of paper, or these days, click a button on a tablet. But the fight over who gets to participate in this most fundamental democratic act has never been simple.

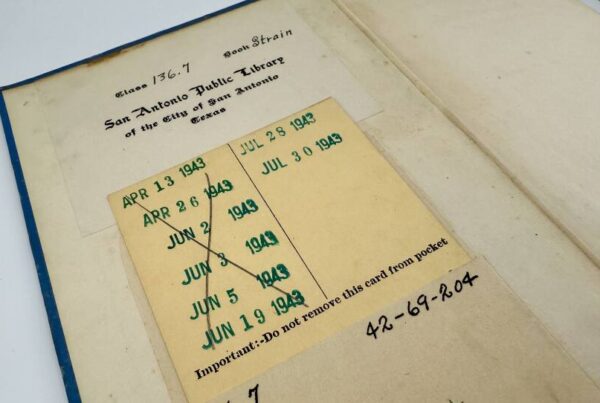

This month marks the 60th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which did more than nearly any other piece of legislation to extend the right to vote in Texas and across the country. President Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas signed the act into law at a time when Texas elections were defined by segregation and discriminatory voting practices.

The Voting Rights Act opened the ballot box to millions of Texans, but the fight over voting rights in Texas continues to this day.

The Voting Rights Act was “the culmination of nearly a century of effort on the part of African Americans broadly, but not exclusively, to make America more democratic,” Ashley Farmer, associate professor of African & African Diaspora Studies and History at UT Austin, told Texas Standard.

In 1870, the 15th amendment outlawed voting discrimination on the basis of race, but systematic violence and intimidation, often in the form of poll taxes, literacy tests and grandfather clauses restricted Black Americans’ ability to vote for nearly a century.

Efforts to register Black voters in the mid-twentieth century swelled into a movement with national support after Freedom Summer in 1964, when the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Congress of Racial Equality organized registration drives in Mississippi in the face of violent attacks, Farmer said.

Another pivotal moment in galvanizing support for federal voting rights legislation was “Bloody Sunday” in the spring of 1965, when civil rights activists attempting to march from Selma to Montgomery were brutally beaten by Alabama state troopers and local police when they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma. Footage of the violence was broadcast on television nationwide.

“We saw people getting beat with bricks, hoses, trampled by horses, attacked by anything and everything possible by local law enforcement and white bystanders,” Farmer said. “And when this was circulated on the news at that time, it transformed Americans’ understandings of the brutality Black people face in order to even exercise the right to vote and the fact that we were fundamentally not operating in a democracy if we were going to such great lengths to keep them from voting.”

For most of American history, Black Americans in the South were not only prevented from voting through violent intimidation and legal barriers, but they were not even able to register to vote.

The Voting Rights Act had an immediate effect on voter participation. The number of eligible voters swelled, and within a year, nearly 250,000 Black people were registered to vote, according to Farmer.

“Most people don’t realize that we’re not even talking about the act of going into the voting booth and pushing your button or pulling a lever, but for the majority of the time that Black people have been in this country, you could not even put yourself on the voter roll to exercise the franchise,” Farmer told Texas Standard.

» GET MORE NEWS FROM AROUND THE STATE: Sign up for Texas Standard’s weekly newsletters

In the decade after the Voting Rights Act, record numbers of Black Americans were elected to political office at the local, state and national level. It also helped set a clear precedent for determining what constitutes discriminatory practices, shaping future civil rights legislation and litigation.

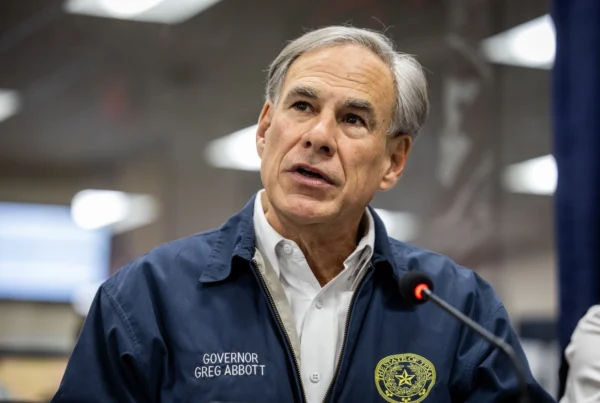

In 2013, the Supreme Court struck down the preclearance clause of the Voting Rights Act in Shelby County v. Holder. Federal approval was no longer required for state and local governments with a long history of voter discrimination, including Texas, to change their voting laws.

Farmer pointed to a number of new voting measures in Texas which would not have been possible before 2013, including new voter ID laws and the closing of certain polling places. These changes, she argues, have disproportionately affected Black and Latino Texans.

Voting rights protections have to be “actively protected,” Farmer told Texas Standard, recalling the recertifications of the Voting Rights Act in the 1970s and 1980s, which solidified and expanded voting protections.

The Voting Rights Act, she argues, illustrates the potential of grassroots activism. In 1965, activism on the ground in Alabama and Mississippi pushed the federal government to act.

“We need vigilance to confront new forms of voter suppression,” Farmer cautioned. “Although the central idea is the same, it looks different in 2025 than it did in 1965.”