Texas is home to eleven of the nineteen owls native to the United States. Among them are some familiar faces like the western screech owl, barred owl and great horned owl.

While you may be familiar with their names, and maybe even their calls, so much about owls has remained shrouded in mystery for millennia. Perhaps that’s why they’ve been the subject of lore and superstition across cultures for eons. But with new advances in technology, we’re learning more about just how complex owls really are – how they hunt, how they communicate, how they think.

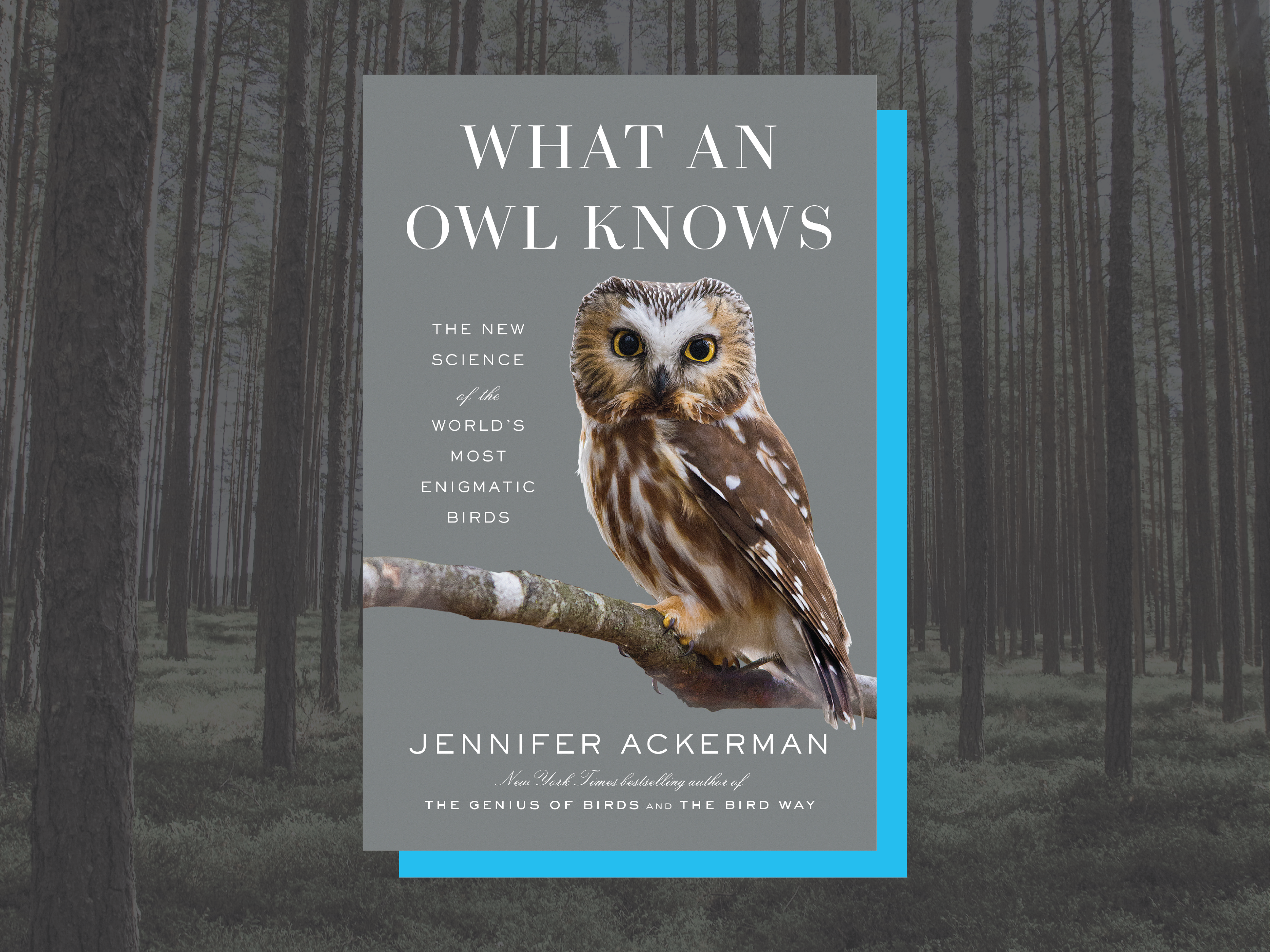

Science writer Jennifer Ackerman joined the Standard to dive into what we know – and what we’re still figuring out – about owls that she covered in her new book “What An Owl Knows: The New Science of the World’s Most Enigmatic Birds.” Listen to the interview above or read the transcript below.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Jennifer Ackerman is the author of “What an Owl Knows: The New Science of the World’s Most Enigmatic Birds.” Photo by Sofia Runarsdo

Texas Standard: What makes owls so enigmatic?

Jennifer Ackerman: Well, because they are so mysterious, so intriguing, and so difficult to study. Scientists have such challenges when they are trying to understand and explore these animals. These birds live in very remote locations. They’re active often at night. So they’re still very largely mysterious. And we’re beginning to use some great new technology to solve some of the new mysteries.

But it has been very challenging. And they are definitely enigmatic.

That’s so interesting. I guess I didn’t think necessarily that, yeah, it’s dark outside when you’re trying to trying to watch these birds is part of the issue. So how has this research changed in the last several years?

So we have used an array of new technology which is really helping out. I mean, we have now kind of new eyes in the field, like infrared cameras, to see what’s going on with owls at night. We have drones to explore those really remote owl habitats. Some owls live in Siberia and very remote areas. We can use drones to investigate those.

We have nest cams that offer us a kind of 24/7 view of intimate owl interactions at the nest. And then we have satellite transmitters which we can actually attach to the backs of some large owls. And those are illuminating the movements of these owls over both short and long distances.

So all that new understanding gleaned from these new technologies – along with the insights from, you know, researchers who have been doing long term studies of owls for decades – are really shedding light on mysteries that have been around for centuries.

This book isn’t your first about the avian world. You’ve published two others, “The Genius of Birds” and “The Bird Way.” Besides how mysterious owls are, what made you want to take a closer look at them?

Well, I think partly because they’re such skilled hunters.

You know, they’re known as wolves of the sky. I had a little Eastern screech owl roosting in behind my house for one spring, and I was just amazed at the skill of this little bird. I never saw it come and go from its roosting hall. But in the morning I would find, you know, the wing of a blue jay or one time the whole body of a mourning dove just hanging out of the hole in the box and then the owl would pull it inside and finish off its meal, you know.

So I was fascinated by the kind of remarkable sensory superpowers they have, their extraordinary hearing and their vision in dim light that allows them to really pinpoint their prey in pitch dark. And then they have this quiet flight. You know, they have wings and feathers that are just so beautifully adapted that their flight is virtually silent.

So I’m just, you know, fascinated by the biology and the diversity. There are like 260 species of owls and they range in size from the huge Blakiston’s fish owl – which I once saw in Hokkaido, Japan. It’s the size of a fire hydrant… All the way down to the tiny little elf owl, which is this little nugget of a bird about the size of a small pinecone.