Growing up in the 1960s, Denise Montgomery would count down the days until the second Monday in October, when she got to skip school and go to the State Fair of Texas.

“There is an area at the park where they have the pretty fountains going down the middle,” Montgomery remembers. “We would sit outside on the park bench and we all ate our dinner or whatever. If we were good, we would get some cotton candy.”

But one year, when Montgomery was 10, rain was coming down in sheets and her grandma said they couldn’t go.

“So I was crying, I was boo-hooing by this time,” she says. “I’m going ‘Why can’t we go?’”

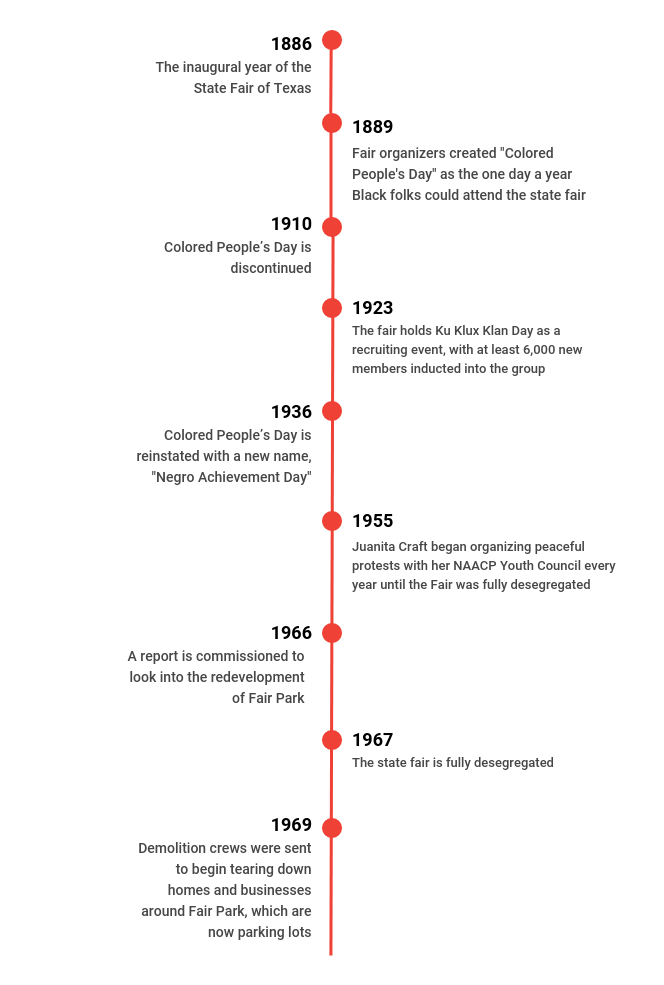

She didn’t realize until years later that the fair was still segregated and Black families like hers could only attend one day a year: Negro Achievement Day.